Have you ever been in a conversation and instinctively taken a small step back? Or felt a sense of unease when a stranger sits right next to you on an otherwise empty park bench? This invisible, unspoken dance of distance is a fundamental part of human interaction, a silent language we all speak without even realizing it. This fascinating field of study has a name: proxemics.

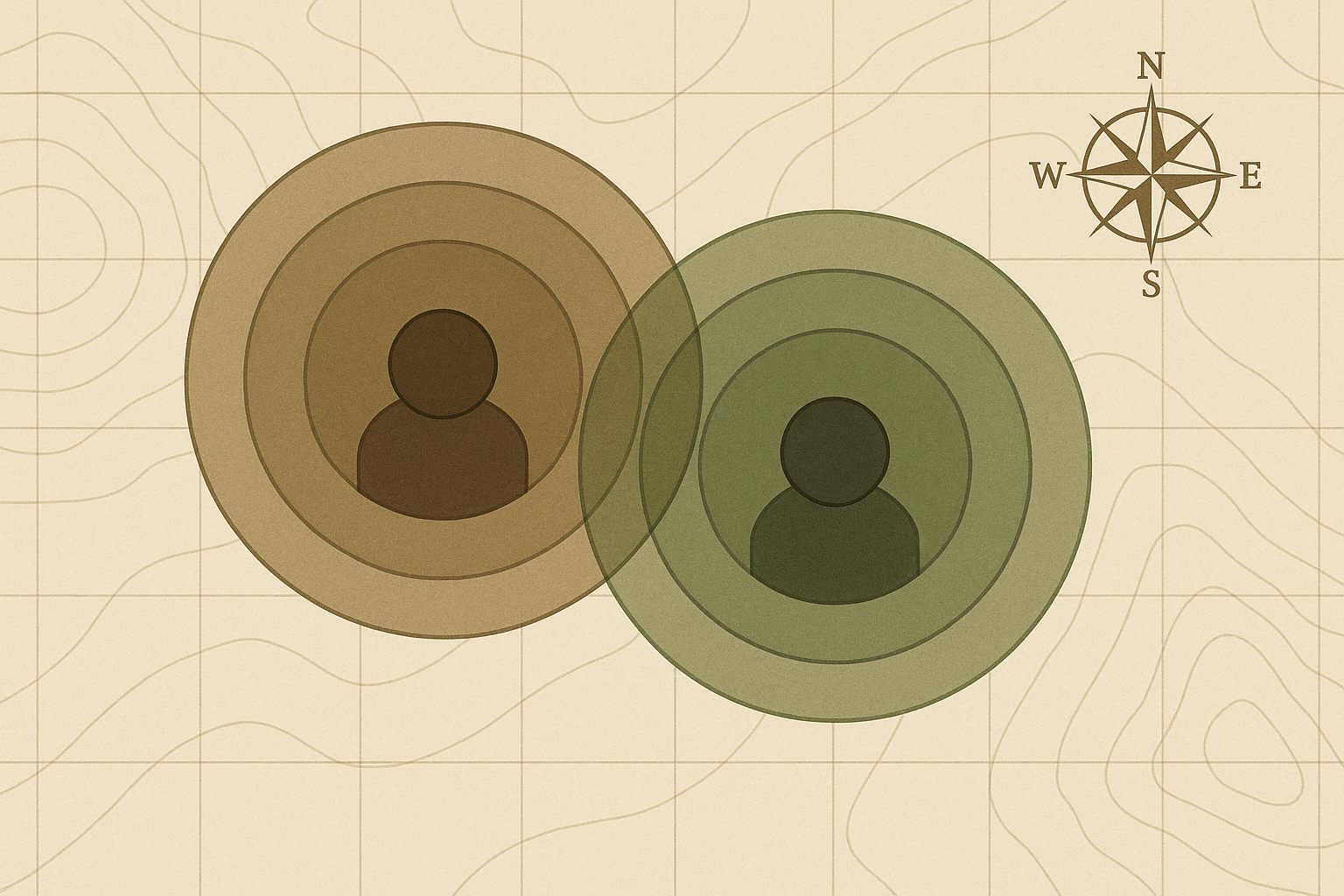

Coined by anthropologist Edward T. Hall in the 1960s, proxemics is the study of how humans use space and the effects that population density, physical environments, and cultural norms have on our behavior and communication. It’s a key component of non-verbal communication, acting as an invisible map that dictates the geography of our social interactions. For a blog focused on geography, there’s no richer territory to explore than the one we carry around us every day.

The Four Zones of Our Invisible Territory

Before we can map the world, we must first understand our own personal geography. Hall identified four primary zones of interpersonal distance, which he based on his observations of middle-class Americans. While these measurements are not universal—as we’ll soon see—they provide a foundational blueprint for understanding our personal space.

- Intimate Distance (0 to 18 inches / 45 cm): This zone is reserved for our closest relationships—embracing, whispering, and comforting. It’s a space of high sensory input, where touch, smell, and sight are intense. Unwanted entry into this zone by a stranger is a major transgression, triggering feelings of discomfort or threat.

- Personal Distance (1.5 to 4 feet / 45 to 120 cm): This is the “personal bubble” we maintain when interacting with good friends and family. It’s close enough for easy conversation but maintains a small physical buffer. A handshake occurs at the edge of this zone.

- Social Distance (4 to 12 feet / 1.2 to 3.6 m): The standard distance for impersonal business, conversations with acquaintances, or new colleagues. It’s a more formal zone where interactions are less personal and more functional. Think of the distance between you and a shopkeeper or a new employee in a meeting.

- Public Distance (12 feet / 3.6 m or more): This is the space for public speaking, lectures, and performances. At this distance, communication becomes more formal, requiring louder speech and grander gestures.

These zones form the basic coordinates of our personal map. But the scale of this map changes dramatically as we travel across the globe.

A Global Atlas of Personal Space

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of proxemics is how it varies across different cultures and geographical contexts. What is considered polite in one country can be perceived as cold, aggressive, or strange in another. Geographers and anthropologists often categorize cultures into two broad groups:

“Contact” cultures, typically found in warmer climates like Latin America, the Middle East, and Southern Europe, prefer closer proximity. In countries like Brazil or Italy, standing close enough to touch someone’s arm while talking is common and signifies warmth and engagement. Backing away in such a context could be misinterpreted as rude or unfriendly.

“Non-contact” cultures, common in colder climates like Northern Europe, North America, and East Asia, tend to maintain more space. In Germany or Japan, personal space is highly valued, and physical contact between colleagues or acquaintances is minimal.

Case Studies in Proxemic Geography:

- Japan: Japan is a classic example of a “non-contact” culture. The traditional bow is a form of greeting that masterfully maintains personal distance. In conversation, people stand further apart than Westerners typically do, and physical touch is rare. This cultural norm is reflected in public behavior, where maintaining order and individual space, even in crowds, is paramount.

- The Middle East: In many Arab cultures, standing very close to someone of the same gender during a conversation is a sign of trust and hospitality. The concept of a personal bubble is much smaller, and conversations can involve a degree of physical contact that might feel intrusive to a Northern European or American.

- Scandinavia: At the other end of the spectrum, Scandinavian countries are famous for their large personal space requirements. The internet is filled with humorous images of Swedes or Finns standing at a bus stop, each person positioned meters apart in a perfect, socially-distanced line. While a caricature, it highlights a cultural preference for a much larger personal and social distance.

- United States: The U.S. is a cultural melting pot, and its proxemics are a mix. Generally considered a “non-contact” culture, Americans value their personal bubble (around arm’s length), yet the firm handshake is a staple of business. However, regional differences exist—the bustling, close-quarters norms of New York City are different from the wide-open spaces and larger personal distances you might find in a rural Texan town.

Urban Landscapes and the Proxemic Squeeze

Nowhere is the geography of personal space more tested than in our planet’s sprawling cities. High population density is a geographical phenomenon that forces a constant negotiation of proxemic norms. How do we cope when our intimate zone is invaded by hundreds of strangers every day?

Think of a crowded subway car in Tokyo, a packed train in Mumbai, or the London Underground during rush hour. In these situations, the conventional rules of proxemics are temporarily suspended. We enter what is functionally an intimate distance with complete strangers, a scenario that would be highly alarming in any other context. To cope, we employ a set of unwritten rules:

- Avoid eye contact at all costs.

- Face forward and keep your body squared.

- Minimize any physical movement.

- Create a psychological barrier with headphones or a book.

This is a collective adaptation to a geographical reality. We allow our physical space to be breached by creating a larger “mental space.” The architecture of a city also plays a role. Wide, open plazas like Piazza Navona in Rome encourage public gathering and social interaction, while the design of public benches with individual dividers is a physical manifestation of a culture’s desire to enforce personal space even in a shared environment.

Conclusion: Your Own Invisible Map

Proxemics is more than just a fascinating social theory; it is the invisible geography that shapes our daily existence. The “bubble” we inhabit is not a fixed dimension but a fluid boundary drawn by our culture, shaped by our environment, and constantly renegotiated in every interaction we have.

From the layout of our living rooms to the way we queue for coffee, we are all cartographers of personal space. By understanding the unspoken rules of this map—both our own and those of others—we can navigate our increasingly interconnected world with greater empathy, awareness, and success. The next time you feel that instinctive urge to take a step back or forward, remember you’re not just moving your body; you’re redrawing a line on a complex and deeply human map.