Picture a vibrant, green oasis flourishing in the heart of a sun-scorched desert. You might imagine a natural spring or a river, but for thousands of years, the lifeblood of many such settlements was something far more ingenious: a hidden, man-made underground river. This incredible feat of engineering is the qanat, a testament to humanity’s ability to adapt and thrive in the most challenging environments.

Stretching for miles beneath the earth, these subterranean aqueducts are more than just historical curiosities; they are masterpieces of sustainable design that hold profound lessons for our water-scarce world.

What is a Qanat? The Genius of Gravity

At its core, a qanat (also known as karez, khettara, galería, or aflaj depending on the region) is a gently sloping tunnel that taps into an underground water source and channels it, using only gravity, to a settlement or agricultural area. Unlike a modern well that requires a pump and constant energy, a qanat is a passive system that flows continuously, day and night.

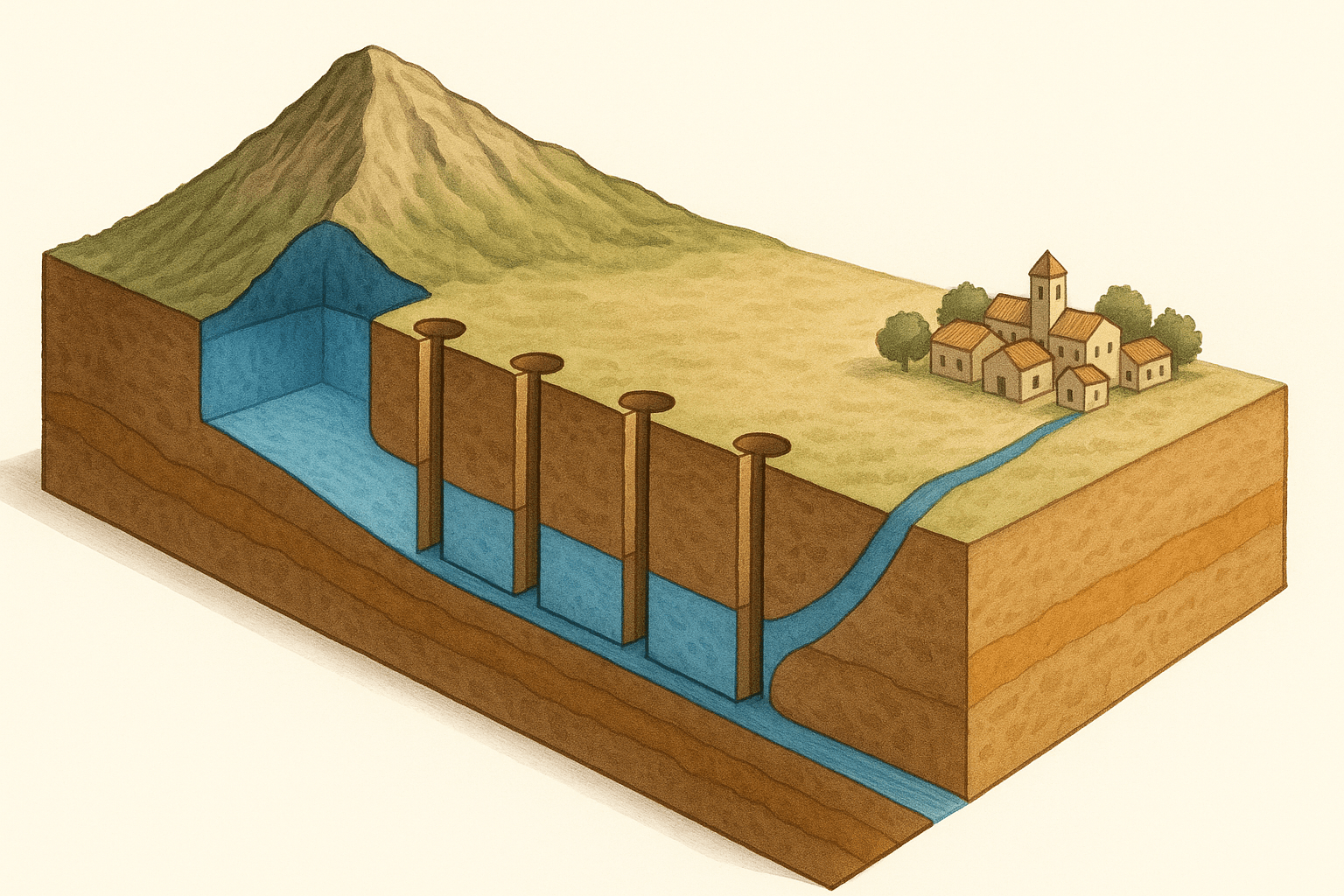

The system is elegantly simple in concept but requires immense skill to construct. It consists of several key components:

- Mother Well (Pedar Chah): The source of the qanat. This is a deep well dug into a hillside or an alluvial fan at the base of mountains to tap into the water table.

- The Qanat Tunnel (Kuran): A nearly horizontal tunnel, with a gradient just steep enough to allow water to flow but not so steep as to cause erosion (often a slope of 1:1000 or 1:1500).

- Vertical Access Shafts (Mil-e Chah): A series of vertical wells dug from the surface down to the main tunnel. These shafts provide ventilation for the diggers and are used to remove excavated earth. From the air, a line of qanat shafts looks like a string of giant molehills marching across the desert landscape.

- Outlet (Mazhar): The point where the water finally emerges from the tunnel onto the surface, often feeding into a reservoir or a network of irrigation channels to sustain a community.

An Engineering Marvel: The Art of the Muqanni

Building a qanat was a dangerous, back-breaking, and highly specialized task undertaken by skilled artisans known as muqannis. This traditional knowledge was often passed down through generations. The construction process was a marvel of precision surveying and manual labor.

First, the muqannis had to identify a promising water source, typically a water-rich alluvial fan where rainwater from mountains seeps underground. After digging a series of test wells to locate the aquifer and determine its depth, they would plot the course of the qanat.

Herein lies the true genius: the main tunnel was dug uphill from the desired outlet towards the mother well. This counter-intuitive method ensured that water would drain away from the diggers, preventing flooding in the tunnel. The muqanni would use simple tools—a plumb line, a level, and a compass—to maintain an incredibly precise, gentle gradient over many kilometers. Any error could cause the water to pool and stagnate or flow too fast and destroy the tunnel.

As they dug horizontally, vertical shafts were excavated every 20 to 50 meters to the surface. Workers would haul baskets of earth up these shafts, creating the characteristic crater-like mounds that are the only visible sign of the vast network below.

A Journey Across Arid Lands: The Geographic Distribution of Qanats

While most strongly associated with Iran, the qanat system is a geographical phenomenon that spread across the arid and semi-arid regions of the world, a testament to its effectiveness.

The Persian Heartland: Iran

The technology originated in ancient Persia (modern-day Iran) over 3,000 years ago. Iran is home to the oldest, longest, and deepest qanats in the world. The city of Yazd, a stunning desert metropolis, owes its existence to an extensive qanat system. Its architecture, including its famous badgirs (windcatchers), was often integrated with the qanats to provide natural air conditioning. In 2016, UNESCO recognized the Persian Qanat as a World Heritage site, citing eleven representative qanats, including the astonishingly deep Qasabeh Qanat in Gonabad, which reaches a depth of over 300 meters.

Spreading West: The Middle East and North Africa

The technology spread with empires and trade. In Oman, the similar aflaj irrigation systems (some of which are qanat-style underground channels) are also a UNESCO World Heritage site and remain crucial for date palm cultivation. In North Africa, particularly Morocco, the system is known as khettara. The vast Tafilalt oasis and the palm groves of Marrakech were historically sustained by these underground aqueducts. The system even reached Europe; the Spanish word galería refers to the qanats built in Spain during the Moorish period, particularly in the arid regions of Andalusia.

Echoes on the Silk Road and Beyond

Heading east from Persia, the technology traveled along the Silk Road. In Afghanistan and Pakistan, they are known as karez and have been a vital source of water for centuries. Perhaps the most remarkable example is the Turpan Water System in the Xinjiang province of China. Located in the Turpan Depression, one of the hottest and driest places on Earth, this network of karez channels water from the nearby Tian Shan mountains, making agriculture possible in an otherwise inhospitable landscape.

A Model for Sustainable Water Management

In an age defined by climate change and growing water scarcity, the ancient qanat offers critical lessons in sustainability. Its design is inherently in tune with its environment.

First, it is energy-free. Powered entirely by gravity, it requires no pumps, no electricity, and has a zero-carbon footprint for operation. Second, it dramatically reduces evaporation. By keeping water underground and away from the intense desert sun, it prevents the massive water loss that plagues modern surface canals. This is a crucial advantage in arid climates.

Most importantly, the qanat is a self-regulating system that prevents over-exploitation of the aquifer. The amount of water a qanat can draw is directly proportional to the level of the water table. If there is a drought and the water table drops, the flow of the qanat naturally decreases, giving the aquifer a chance to recharge. This is in stark contrast to modern deep-well pumps, which can drain an aquifer dry, leading to land subsidence and irreversible environmental damage.

The management of qanat water also fostered sophisticated social structures. Water rights were complex and meticulously recorded, with communities working together to maintain the system under the guidance of a water master, or mir-ab. The qanat was not just an infrastructure project; it was the social and economic backbone of the community.

Today, many qanats have fallen into disrepair, replaced by seemingly more convenient modern pumps. The traditional knowledge of the muqannis is fading. Yet, as we search for resilient solutions to modern problems, this ancient technology stands as a powerful reminder that sometimes, the most sustainable path forward involves looking back to the wisdom of our ancestors. The quiet, hidden qanat, flowing silently beneath the desert, is a profound symbol of living in harmony with the geography of our planet.