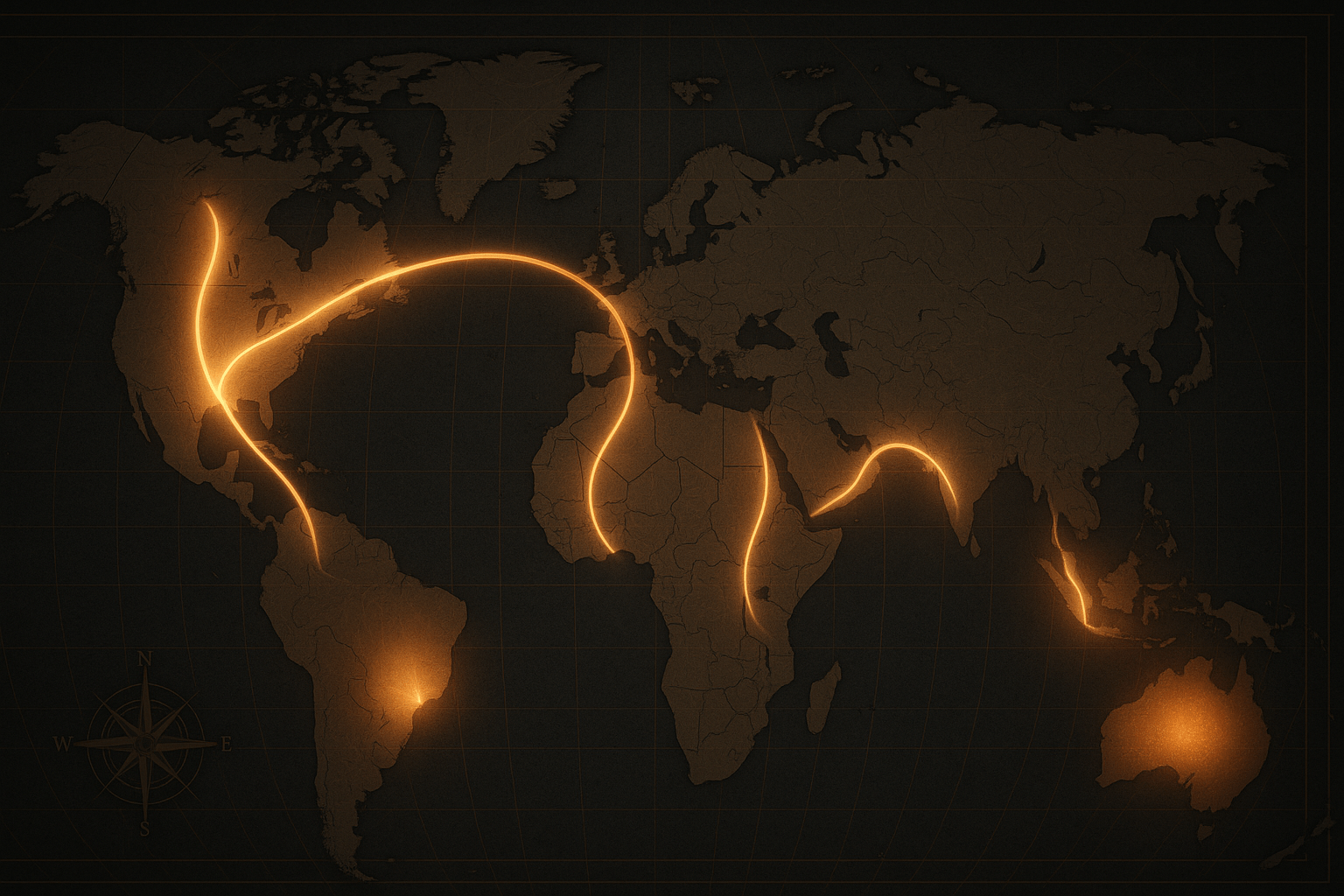

Look at a physical map, and you’ll see the Earth’s great arteries: the Nile, the Amazon, the Mississippi. These rivers carve canyons, nourish floodplains, and determine where cities rise and fall. But what if we could map another set of rivers? These are invisible, flowing not with water but with currency. They are the remittance corridors—vast, transnational streams of money sent by migrants and diaspora populations back to their families and communities in their home countries. Totalling over $600 billion annually, these flows are more than just financial transactions; they are powerful geographic forces, reshaping the physical and human landscapes of nations around the globe.

The Anatomy of an Invisible River

A remittance corridor is the channel connecting a specific host country, where migrants work, to a specific recipient country, where their families live. Think of it as a financial pathway with a distinct source and destination. The largest corridors are testament to the major migration patterns of our time: the United States to Mexico, the United Arab Emirates to India, and Saudi Arabia to the Philippines are among the most significant.

These corridors are not abstract concepts. They are comprised of a complex network of physical locations—corner-store money transfer agents in Los Angeles, banks in Dubai, fintech apps on a smartphone in London—and an equally complex web of human relationships. Each transaction represents a story of separation, sacrifice, and connection, a financial lifeline stretching across continents and oceans.

The Geography of Arrival: How Money Reshapes the Homeland

While the money is earned in global hubs like New York, Riyadh, or Singapore, its most profound geographical impact is felt thousands of miles away, in the towns and villages of the recipient nations. Here, the invisible rivers of capital become startlingly visible.

Mexico: Building Dreams, One Brick at a Time

The U.S.-Mexico corridor is arguably the world’s most famous. Drive through rural states like Michoacán, Zacatecas, or Oaxaca, and you’ll see the impact immediately. Alongside traditional adobe homes, you’ll find striking two or three-story houses built with modern materials, often in architectural styles echoing suburban America. These are the “casas de remesas” (remittance houses), physical monuments to labor performed in a foreign land. They often sit empty for much of the year, waiting for their owners to return for holidays or retirement, altering the visual and social rhythm of the village.

Beyond individual homes, remittances collectively fund community infrastructure. In many towns, it is money from “el norte” (the north) that paves the roads, renovates the local church, or builds a new basketball court. This creates a parallel form of development, one driven not by the state, but by the coordinated effort of its citizens abroad, fundamentally changing the relationship between a community and its physical space.

The Philippines: From Balikbayan Box to Condominium Boom

For the Philippines, remittances from its nearly 10 million Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) are a cornerstone of the national economy. The geographical expression of this flow begins with the balikbayan box—a simple cardboard box packed with goods like clothes, food, and electronics sent home by OFWs. These boxes are a micro-geographical phenomenon, a physical manifestation of love and provision that connects a specific apartment in Dubai to a specific family home in a province like Batangas.

On a macro scale, remittances have fueled a massive construction boom, particularly in Metro Manila. The city’s skyline is increasingly dominated by residential condominiums, a significant portion of which are purchased by OFWs or their families as a primary investment. This flow of capital has reshaped urban geography, driving property values and creating new residential and commercial hubs. The money earned by a nurse in London or a seafarer in the Atlantic is physically materializing as concrete and glass towers in Quezon City or Makati.

Somalia: A Lifeline Carving Stability from Chaos

In fragile states, remittances are not just for development; they are a lifeline for survival. In Somalia, where formal banking infrastructure is weak or non-existent after decades of conflict, remittances account for an estimated 25-40% of the entire economy. Here, the geography of the corridor is unique, relying heavily on the hawala system.

Hawala is an ancient, trust-based money transfer network. A person in Minneapolis can give cash to a Somali hawaladar (agent), who then calls a trusted counterpart in Mogadishu or Hargeisa, authorizing them to release an equivalent amount to the recipient. It’s a system built on reputation, not regulation, creating a resilient financial geography that operates where banks cannot. This money is rebuilding the physical landscape of Somali cities. It funds the construction of new shops, fuels small markets, and allows for the reconstruction of homes and infrastructure destroyed by war, slowly carving out pockets of stability and economic activity.

The Friction of Flow and the Future of Corridors

These rivers of money do not flow without friction. High transfer fees charged by traditional money transfer operators have historically acted as a kind of “tax” on migrants, eroding the value of their hard-earned money. This is a geographical issue: the cost of sending money is often highest in corridors where the need is most desperate and formal banking is least accessible.

However, technology is changing the landscape. The rise of mobile money and fintech apps is creating new, more efficient, and cheaper channels. This digital transformation is its own form of geographical change, allowing a construction worker in Qatar to send money directly to a family member’s phone in a remote Filipino village, bypassing physical agents entirely and redrawing the map of financial access.

Ultimately, remittance corridors are a fundamental feature of our interconnected world. They are a testament to human mobility, economic disparity, and enduring family ties. The next time you look at a world map, remember the invisible rivers flowing across its borders. They may not be marked in blue, but they are carving new realities into the Earth’s surface, building houses, paving roads, and shaping the future of nations one transaction at a time.