Russia is a paradox. It is the largest country on Earth by landmass, spanning eleven time zones and covering over 17 million square kilometers. It is a geographic titan, a vast expanse of tundra, taiga, and steppe, rich in natural resources that fuel global economies. Yet, this giant is hollowing out from the inside. For decades, Russia has been in the grips of a profound demographic crisis, a slow-motion decline that threatens its economic future, its military power, and its very control over its immense territory.

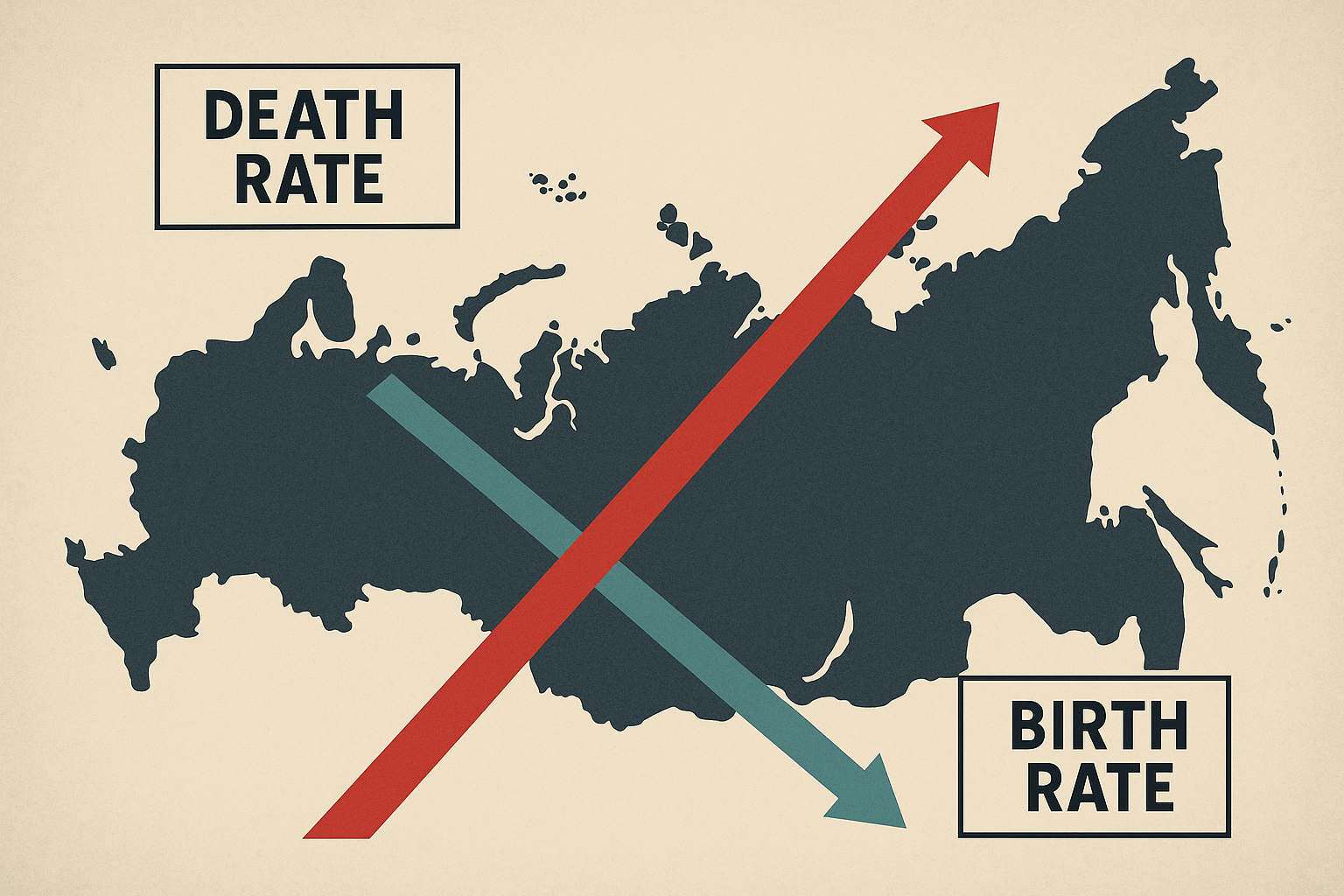

At the heart of this crisis is a stark, grim visualization known as the “Russian Cross.”

The Anatomy of the Russian Cross

Imagine a simple line graph charting a country’s birth and death rates over time. In a healthy, growing population, the birth rate line stays comfortably above the death rate line. In post-Soviet Russia, something terrifying happened. In the early 1990s, following the collapse of the USSR, the birth rate plummeted while the death rate soared. The two lines crossed in 1992, creating a “cross” on the graph that signifies more people dying than being born. This wasn’t a temporary blip; it became a persistent feature of Russia’s human geography.

While government initiatives and a period of economic stability in the 2000s managed to briefly push the lines back to a more natural order, the cross has reappeared. The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have exacerbated the trend, sending death rates up and future birth prospects down. The numbers mask an even more critical detail: the decline is most severe among ethnic Russians, the state-forming group that makes up nearly 80% of the population.

What Fuels the Decline?

The Russian Cross is the result of a perfect storm of geographic and social factors:

- High Death Rates: The primary driver is a tragically low life expectancy, particularly for men. The economic chaos of the 1990s decimated the public healthcare system. This was compounded by deep-seated lifestyle issues, including some of the world’s highest rates of alcoholism and smoking, leading to rampant cardiovascular disease. For Russian men, the average life expectancy hovers in the mid-60s, a figure more akin to a developing nation than a global power.

- Low Birth Rates: The economic instability that fueled high death rates also crushed birth rates. Families facing an uncertain future were hesitant to have children. This added to a long-term trend of urbanization and female education, which universally corresponds with smaller family sizes. Russia is also still feeling the “demographic echo” of World War II, where the immense loss of life created a smaller generation, which in turn produced an even smaller one, a ripple effect that continues today.

The Geography of a Shrinking Nation

Russia’s demographic crisis is not spread evenly across its vast territory. Its effects create a patchwork map of growth and decay, revealing deep vulnerabilities.

The Hollow Heartland

The demographic winter is harshest in the traditional ethnic Russian heartland—the regions west and south of Moscow. Oblasts like Pskov, Tver, Smolensk, and Tula are ground zero for the Russian Cross. These are largely rural, aging regions that have seen decades of out-migration as young people leave for the economic opportunities of the big cities. Villages are abandoned, their wooden houses slowly collapsing back into the earth. The landscape is becoming emptier, a quiet testament to a disappearing population.

Pockets of Growth, Shifting Balances

In stark contrast to the Slavic heartland, Russia’s periphery tells a different story. The Muslim-majority republics of the North Caucasus, such as Chechnya, Dagestan, and Ingushetia, boast much higher birth rates, rooted in more traditional, conservative social structures. This creates a slow but significant demographic shift within the Russian Federation, altering its ethnic and religious composition. While Moscow remains firmly in control, the long-term reality is a Russia where the non-Slavic population is growing while the ethnic Russian core shrinks.

The megacities of Moscow and St. Petersburg also appear to defy the trend, but this is an illusion. They don’t have high birth rates; rather, they act as demographic vacuums, sucking in ambitious internal migrants from the dying provinces and skilled immigrants from Central Asia. They are vibrant hubs of activity that mask the silent decay of the vast hinterland that surrounds them.

Siberia: The Empty Treasure Chest

Nowhere are the geopolitical implications of Russia’s demography more stark than in Siberia and the Russian Far East. This enormous territory, stretching from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, is a storehouse of global resources: oil, natural gas, diamonds, gold, timber, and fresh water. It is strategically vital to Russia’s status as an energy superpower.

It is also profoundly empty. With a population density of less than three people per square kilometer, Siberia is one of the most sparsely populated regions on Earth. And it’s getting emptier. The Soviet system propped up cities in punishing climates to extract resources, but since its collapse, people have been fleeing the harsh conditions and lack of opportunity for the relative comfort of European Russia.

This creates a glaring geopolitical vulnerability. To the south of this underpopulated, resource-rich land lies a demographic and industrial giant: China. With a population over ten times that of Russia’s, a ravenous appetite for natural resources, and a presence that is already felt through investment and labor, China looms large over Siberia’s future.

Implications for a Global Power

A country’s power is more than just its landmass; it is its people. Russia’s demographic decline directly undermines its claim to great power status.

A Crisis of Manpower

The most immediate impact is on military strength. A shrinking pool of young men means fewer potential conscripts to fill the ranks of the military. The war in Ukraine has thrown this issue into sharp relief. Russia has struggled to generate sufficient manpower, resorting to unpopular mobilizations, recruiting from prisons, and relying on ethnic minorities from regions like Dagestan and Buryatia to fill frontline roles. A nation cannot sustain a large, conventional military force without a healthy population of young people, forcing a greater reliance on its nuclear arsenal as a deterrent.

Economic Stagnation and Sovereign Control

Fewer people means a smaller workforce, less economic dynamism, and an ever-increasing burden on the state to support a growing population of pensioners. This economic stagnation limits Russia’s ability to invest in infrastructure, technology, and, crucially, the defense of its own territory.

This brings us back to Siberia. How can a shrinking, economically strained Russia effectively govern and secure a territory so vast and empty, especially when its powerful, resource-hungry neighbor is right next door? While a military invasion from China is unlikely, a “soft” takeover through economic dominance, demographic settlement, and infrastructure control is a scenario that haunts strategic thinkers in Moscow.

The Russian government is acutely aware of the problem, implementing pro-natalist policies like “maternity capital” payments to encourage larger families. But these measures have had limited success against the powerful tides of economic reality and social change. The Russian Cross is more than a statistic; it is a geographic force reshaping the country’s destiny. It is the quiet crisis that could ultimately determine whether the Russian titan can hold onto its own vast lands.