Imagine a landscape so vast and flat that the horizon disappears, blurring the line between earth and sky. During the day, it’s a blindingly white expanse of hexagonal salt tiles stretching to infinity. After a rain, it transforms into the world’s largest mirror, perfectly reflecting the clouds and stars above. This isn’t a scene from another planet; it’s the surreal beauty of a salt pan, one of Earth’s most stunning and unique geographical phenomena.

The Recipe for a Natural Mirror: How Salt Pans Form

Salt pans, also known as salt flats or by their Spanish name salar, are not created overnight. They are the geological ghost of a bygone era, the remnants of ancient lakes and seas. The process begins with a specific type of landform: an endorheic basin. This is essentially a giant bowl in the Earth’s crust with no outlet to the sea. Rivers and streams flow into the basin, but the water has no escape route except through evaporation.

Over thousands, sometimes millions, of years, this cycle repeats. Water carrying dissolved minerals and salts from the surrounding mountains and terrain collects in the basin. As the climate changes or the seasons turn, the intense sun beats down, causing the water to evaporate. While the water vanishes into the atmosphere, the salts and minerals it carried are left behind. Millennia of this process concentrates the minerals, building up a thick, hard crust of salt, often several meters deep. The result is an incredibly flat, expansive landscape of crystallized minerals, primarily sodium chloride (table salt), but also gypsum and other potassium, magnesium, and lithium salts.

A Geographical Tour of Earth’s Great Salt Pans

While the formation process is similar, each salt pan has its own unique character, shaped by its specific location, history, and climate. Let’s take a journey to some of the most famous examples.

Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia: The Crown Jewel

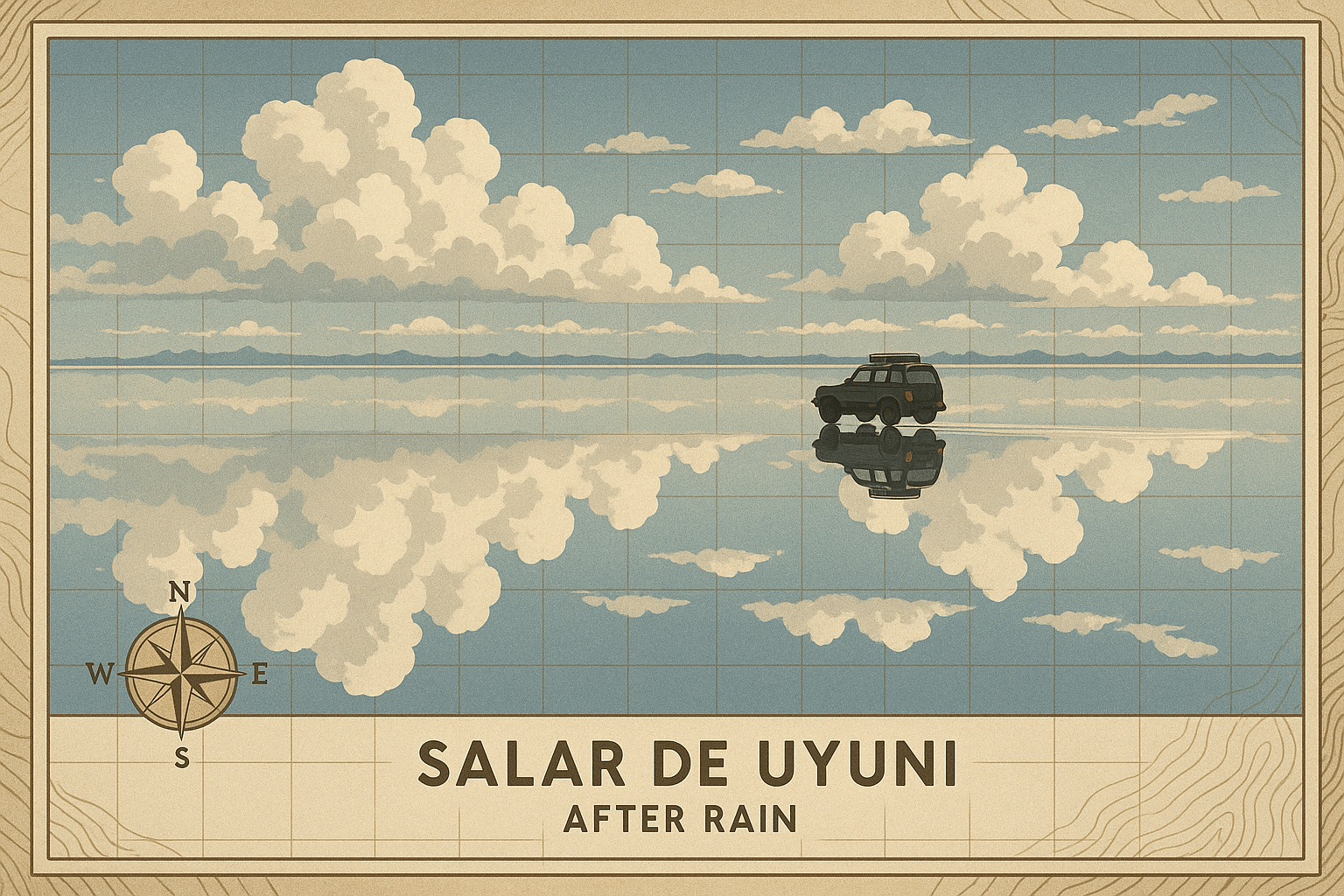

Located high in the Andes mountains on the Bolivian Altiplano, Salar de Uyuni is the undisputed king of salt pans. Spanning over 10,500 square kilometers (4,086 square miles), it is the largest in the world. This vast white desert is what remains of the prehistoric Lake Minchin. What makes Uyuni globally famous is its “mirror effect.” During the rainy season (roughly December to April), a thin layer of water covers the salt crust. Because the surface is so exceptionally flat, this water creates a flawless reflection of the sky, producing breathtaking and surreal photo opportunities that attract tourists from every corner of the globe. In the heart of the salar lies Isla Incahuasi, a rocky outcrop covered in ancient, giant cacti—a startling, living island in a sea of salt.

Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah, USA: A Need for Speed

In the American West lies another iconic salt pan: the Bonneville Salt Flats. A remnant of the massive Pleistocene-era Lake Bonneville, which once covered a third of modern-day Utah, this area is a testament to a much wetter past. The geography of the Bonneville Salt Flats—its hard, flat, and smooth surface—has made it synonymous with human ingenuity and the quest for speed. It is home to the “Bonneville Speedway”, a world-renowned venue for land speed racing where numerous records have been broken. Here, human geography and physical geography collide as drivers push their machines to the limit on a surface forged by ancient climate change.

Etosha Pan, Namibia: A Hub for Wildlife

Not all salt pans are defined solely by their stark emptiness. The Etosha Pan in northern Namibia is the heart of one of Africa’s greatest wildlife sanctuaries, Etosha National Park. For most of the year, it is a dry, dusty, saline depression. However, during the brief rainy season, it can partially fill with water, attracting thousands of wading birds, including spectacular flocks of flamingos. The springs and waterholes along the edges of this massive pan are a lifeline for an incredible diversity of animals, from elephants and rhinos to lions and giraffes, making it a powerful example of how a seemingly inhospitable environment can support a vibrant ecosystem.

Human Geography: From Tourism to Technology

These otherworldly landscapes are far more than just geological curiosities; they are deeply intertwined with human activity, shaping both local economies and global technologies.

The Draw of the Otherworldly: Tourism

The sheer visual spectacle of salt pans makes them powerful magnets for tourism. Salar de Uyuni is the prime example. The economy of the nearby city of Uyuni is almost entirely dependent on the 4×4 tours that ferry visitors across the salt flats. These tours offer unique experiences, from visiting hotels made entirely of salt blocks to creating perspective-bending photographs on the featureless white plain. This tourism provides a vital source of income for local communities in what is one of South America’s poorest regions.

White Gold: The Lithium Rush

Beneath the crystalline crust of many salt pans lies a resource critical to our modern world: lithium. The brine trapped in the salt deposits is rich in this light metal, an essential component in rechargeable batteries for smartphones, laptops, and, most significantly, electric vehicles (EVs).

This has turned the high-altitude deserts of South America into a 21st-century resource hub. The “Lithium Triangle“, an area overlapping Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, is estimated to hold over half of the world’s lithium reserves. Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia and the nearby Salar de Atacama in Chile are at the epicenter of this “white gold” rush. The extraction process involves pumping the brine into vast evaporation ponds, a method that is relatively cheap but raises significant environmental concerns. In some of the driest places on Earth, this process consumes enormous quantities of water, potentially impacting fragile ecosystems and the water supplies of local indigenous communities.

Balancing Beauty and Demand

Salt pans are truly remarkable places. They are natural art installations, windows into our planet’s climatic past, and fragile ecosystems. Today, they also sit at the crossroads of preservation and progress. As we look to a future powered by green technology, the demand for the lithium beneath their surfaces will only grow. The challenge lies in managing these unique geographical treasures sustainably, ensuring that their surreal beauty and economic potential can coexist without destroying the very landscapes that captivate and provide for us.