Every object in our globalized world has a life cycle. Your smartphone, your t-shirt, the coffee beans for your morning brew—they all begin a journey somewhere and end it somewhere else. But what about the colossal vessels that make this journey possible? Where do the 300-meter-long container ships, the mammoth oil tankers, and the aging cruise liners go when their service life is over?

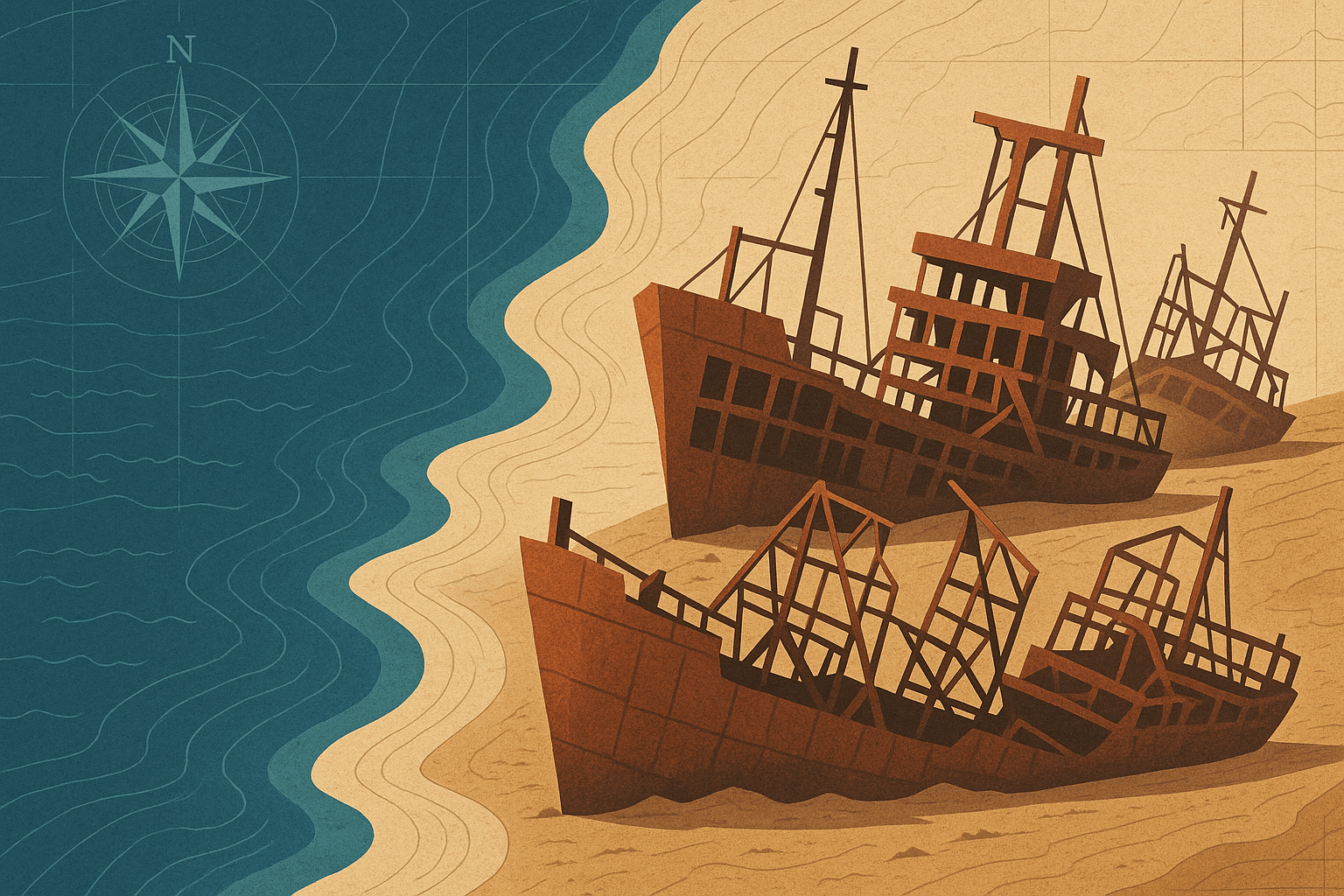

They don’t sink to the bottom of the ocean in some grand, watery funeral. Instead, most are deliberately run aground on a handful of specific beaches in South Asia, where they are torn apart, piece by piece, by hand. This is the world of ship-breaking, and its geography tells a powerful story of tides, trade, and tragedy.

The Geography of Deconstruction

The business of dismantling ships is not randomly distributed across the globe. It is a hazardous, labor-intensive industry that has become spatially concentrated in a few key locations, primarily on the coastlines of India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. The reason for this clustering is a stark intersection of physical and human geography.

From a human geography perspective, the drivers are economic. These nations offer low-cost labor and, historically, have had less stringent environmental and worker safety regulations. For a ship owner, selling a vessel for scrap to a yard in South Asia is far more profitable than paying for a costly, highly regulated dismantling process in Europe or North America. The scrap steel recovered is a vital resource for the domestic construction industries of these developing countries, creating a powerful local incentive to keep the industry going.

But it is the physical geography that makes these specific locations possible. The primary method used here is called “beaching.” To beach a vessel that weighs tens of thousands of tonnes, you need a very particular set of coastal conditions:

- A Massive Tidal Range: The most crucial factor is a large difference between high tide and low tide, known as a macro-tidal environment. During the highest tides (spring tides), ships are sailed at full speed and rammed onto the shoreline, pushing them as far up the beach as possible. When the tide recedes, it leaves the ship stranded high and dry, ready for the army of workers who swarm it.

- A Gentle, Wide Slope: The intertidal zone—the area of the beach exposed between high and low tide—must be vast and have a gentle gradient. This allows the massive ships to settle securely on the muddy or sandy bottom without tipping over.

- Sheltered Waters: The locations are typically in protected gulfs or bays, shielding the operation from the full force of open-ocean waves and storms.

This unique combination of economic incentives and tidal geomorphology has turned specific stretches of coastline into the world’s biggest ship graveyards.

Spotlight on the Graveyards: Alang and Chittagong

Nowhere is this phenomenon more visible than on the beaches of Alang, India, and Chittagong, Bangladesh. Together, they handle the vast majority of the world’s end-of-life tonnage.

Alang, India: The World’s Largest Shipyard

Stretching for over 10 kilometers along the Gulf of Khambhat in the Indian state of Gujarat, Alang is the undisputed king of ship-breaking. Its geographical advantage is its phenomenal tidal range. The tides here can vary by more than 10 meters (33 feet), among the highest in the world. This immense power of the sea is harnessed twice a month during the spring tides to deliver new hulks to the shore.

Once a ship is beached, a meticulously organized, if brutally dangerous, process begins. Thousands of migrant workers, mostly from India’s poorest states, descend on the vessel. With little more than blowtorches and brute force, they carve the ship into transportable sections. The entire landscape is surreal: a graveyard of steel skeletons in various states of decay, a shoreline stained with oil and rust, and a bustling secondary economy. An entire city has sprung up behind the beach, selling everything salvaged from the ships—from lifeboats and engine parts to furniture and cutlery from the galley.

Chittagong, Bangladesh: A Lifeline of Steel

Along the coast of Sitakunda, just north of the major port city of Chittagong in Bangladesh, lies the world’s second-largest ship-breaking area. The geography is similar to Alang’s, with vast tidal mudflats bordering the Bay of Bengal providing the perfect platform for beaching.

The human geography here is deeply tied to national development. Bangladesh has almost no domestic iron ore reserves. The ship-breaking industry, therefore, provides an estimated 60-80% of the country’s steel. It is a critical supply chain for construction and infrastructure, making it a powerful economic and political force. Yet, this reliance comes at a tremendous human and environmental cost, with conditions in Chittagong often cited as being even more perilous than in Alang.

The Dark Side of the Tide

While the geography makes this industry possible, it also makes it an environmental nightmare. The beaching method means there is no containment for the hazardous materials locked within these old ships. As workers cut through the steel, a toxic cocktail leaches directly into the sand and is washed out to sea with the next high tide.

This toxic brew includes:

- Asbestos: Used for insulation in older ships, its fibers cause fatal lung diseases.

- PCBs (Polychlorinated Biphenyls): Carcinogenic coolants and lubricants.

- Heavy Metals: Lead from paint, mercury in electrical switches, and cadmium from wiring.

- Oil and Fuel Sludge: Thousands of liters of residual toxic fuels and oils contaminate the coastal ecosystem.

The human toll is equally devastating. Workers face constant risks of falling from great heights, being crushed by steel plates, or suffering from explosions in fuel tanks that haven’t been properly cleaned. Long-term exposure to toxic fumes and materials leads to chronic illness, with little access to healthcare.

A Shifting Map? The Future of Ship Recycling

International pressure and growing awareness have led to calls for change. The Hong Kong Convention, adopted in 2009, is an international treaty aimed at ensuring that ships are recycled in a safe and environmentally sound manner. However, its ratification and enforcement have been slow.

Greener alternatives do exist. In places like Turkey and some European countries, ships are dismantled in contained environments like dry docks. Here, pollutants can be captured and disposed of safely. But this “green recycling” is significantly more expensive, and the geography is different—it relies on industrial port infrastructure, not natural tidal flats.

For now, the powerful economic geography of South Asia remains dominant. As long as it is vastly cheaper to send a ship to a beach in Alang or Chittagong, the laws of global capitalism will likely steer them there. These beach graveyards are the final, hidden destination in the supply chain that brings us our modern lives—a stark, unsettling reminder of the true cost of global commerce, written onto the very landscape of our planet.