The Geographical Predicament: An Island in a Malay Sea

To understand Singapore’s language policy, one must first look at a physical map. Singapore is a tiny, resource-poor island located at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, flanked by its much larger neighbors, Malaysia and Indonesia. It sits in what its founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, famously described as “a Malay sea.” This geographical reality presented a profound challenge from its very inception in 1965. As a majority-Chinese nation that had just separated acrimoniously from Malaysia, Singapore had to project an identity that was both distinct yet non-threatening to the region.

This is where language becomes a tool of geopolitical positioning. The decision to make Malay (Bahasa Melayu) the national language, despite Malays being a minority within Singapore, was a masterstroke of diplomacy. The national anthem, “Majulah Singapura” (Onward, Singapore), is sung in Malay. Military commands are given in Malay. This linguistic deference signals respect and acknowledges the geopolitical and cultural context of its location, soothing potential anxieties from its neighbors about a “Third China” emerging on their doorstep.

Engineering Internal Geography: The CMIO Model and the Lingua Franca

While Malay addresses the external geography, the policy’s internal focus is on managing its own complex human geography. Singapore’s population is a dense mosaic of ethnicities, primarily categorized under the state’s official CMIO model: Chinese (around 74%), Malay (13.5%), Indian (9%), and ‘Others’. An outbreak of ethnic strife could shatter the fragile nation. The language policy was designed as the bedrock of social cohesion.

English: The Language of Neutrality and Commerce

The choice of English as the primary language of administration, law, and education was profoundly strategic. As a colonial inheritance, English belonged to everyone and no one, placing all ethnic groups on a level playing field. It prevented the linguistic and cultural dominance of the majority Chinese population, which would have risked alienating the Malay and Indian minorities. More importantly, it plugged Singapore directly into the global circuits of trade, finance, and technology. English was, and is, the language of the international marketplace. By adopting it, Singapore bypassed its regional limitations and branded itself as a global city—a neutral, efficient, and accessible hub for international business.

Mother Tongues: Cultural Anchors in a Globalized World

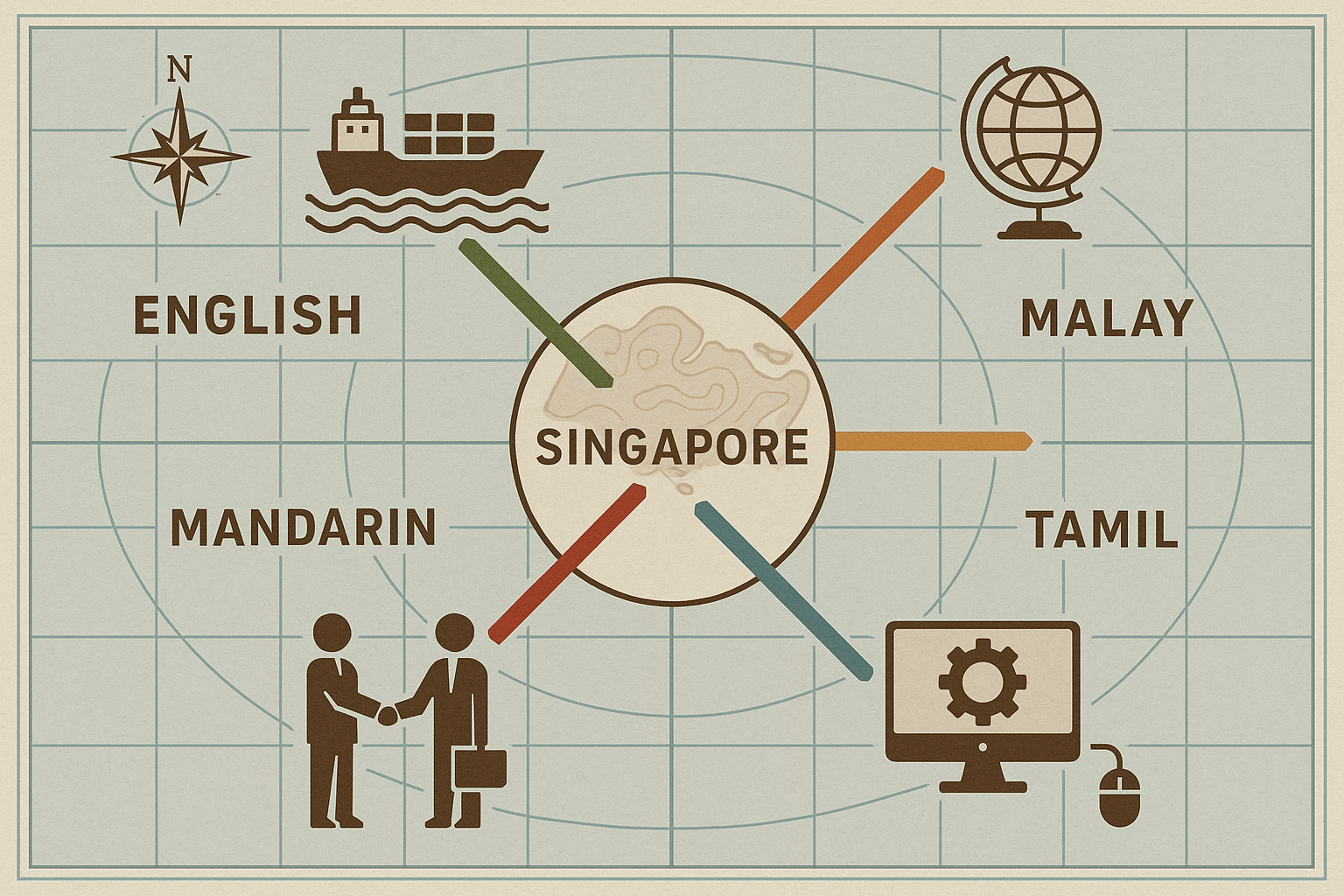

At the same time, the government feared that a wholesale adoption of English would lead to deculturation—creating a disconnected, “Westernized” populace adrift from its Asian roots. The Bilingual Policy was the solution. Every student learns English as their first language and their designated “Mother Tongue” (Mandarin for Chinese, Malay for Malays, and Tamil for Indians) as a second language.

This policy serves two key purposes:

- Cultural Ballast: The mother tongue is meant to act as a cultural anchor, embedding citizen with the values and heritage of their community. This prevents social fragmentation and fosters a rooted identity.

- Economic Asset: As these languages connect to vast and powerful civilizations, they provide a significant economic advantage. The ability to speak Mandarin, in particular, has become a massive boon.

Language as a Bridge and a Shield: Navigating the Regional Map

If English is Singapore’s connection to the world and its mother tongues are its cultural anchors, the combination of these languages becomes a sophisticated tool for navigating the complex map of Asian geopolitics.

Mandarin and the Rise of China: The controversial “Speak Mandarin Campaign”, launched in 1979 to encourage Chinese Singaporeans to speak Mandarin instead of other dialects like Hokkien or Cantonese, had a clear geopolitical dimension. It aimed to create a unified Chinese community that could later engage with a modernizing People’s Republic of China. This foresight paid off handsomely. Today, Singapore’s English-Mandarin bilingualism makes it an indispensable bridge between the West and China. It is perceived as a place where both sides can understand the business culture and legal frameworks of the other, cementing Singapore’s role as a premier hub for finance, logistics, and diplomacy in Asia.

Tamil and the Link to India: While smaller in demographic scale, the official status of Tamil is no less significant. It recognizes the historical contributions of the Indian community and forges a strong connection to the Indian subcontinent, another rising economic and political power. This linguistic link supports trade and diplomatic ties with India, further diversifying Singapore’s partnerships.

In essence, Singapore’s language policy allows it to present a different face to different partners, all while maintaining a consistent core identity. To the West, it is an accessible, English-speaking, rule-of-law nation. To China, it is a culturally savvy, Mandarin-speaking partner. To its immediate neighbors, it is a respectful member of the Southeast Asian community that honors the Malay language. It is this linguistic dexterity that underpins its diplomatic posture of neutrality and its economic strategy of being an open, global hub.

A Living Map: Challenges and the Future

Of course, this top-down linguistic engineering is not without its tensions. The organic, grassroots evolution of “Singlish”—a vibrant creole of English, Mandarin, Malay, Hokkien, and Tamil—is often seen by the government as a threat to formal standards but is cherished by many Singaporeans as a marker of their unique, shared identity. Debates continue over the declining standards of Mother Tongues among the youth and the challenge of adapting the policy to an increasingly diverse immigrant population.

Ultimately, Singapore’s language policy is a living, breathing testament to the power of geography in shaping a nation’s destiny. It is a form of cartography written on the tongues of its people—a deliberate drawing of internal social boundaries and external diplomatic bridges. For this tiny city-state, managing multilingualism is not just a social policy; it is the art of geopolitical survival and prosperity, spoken every single day.