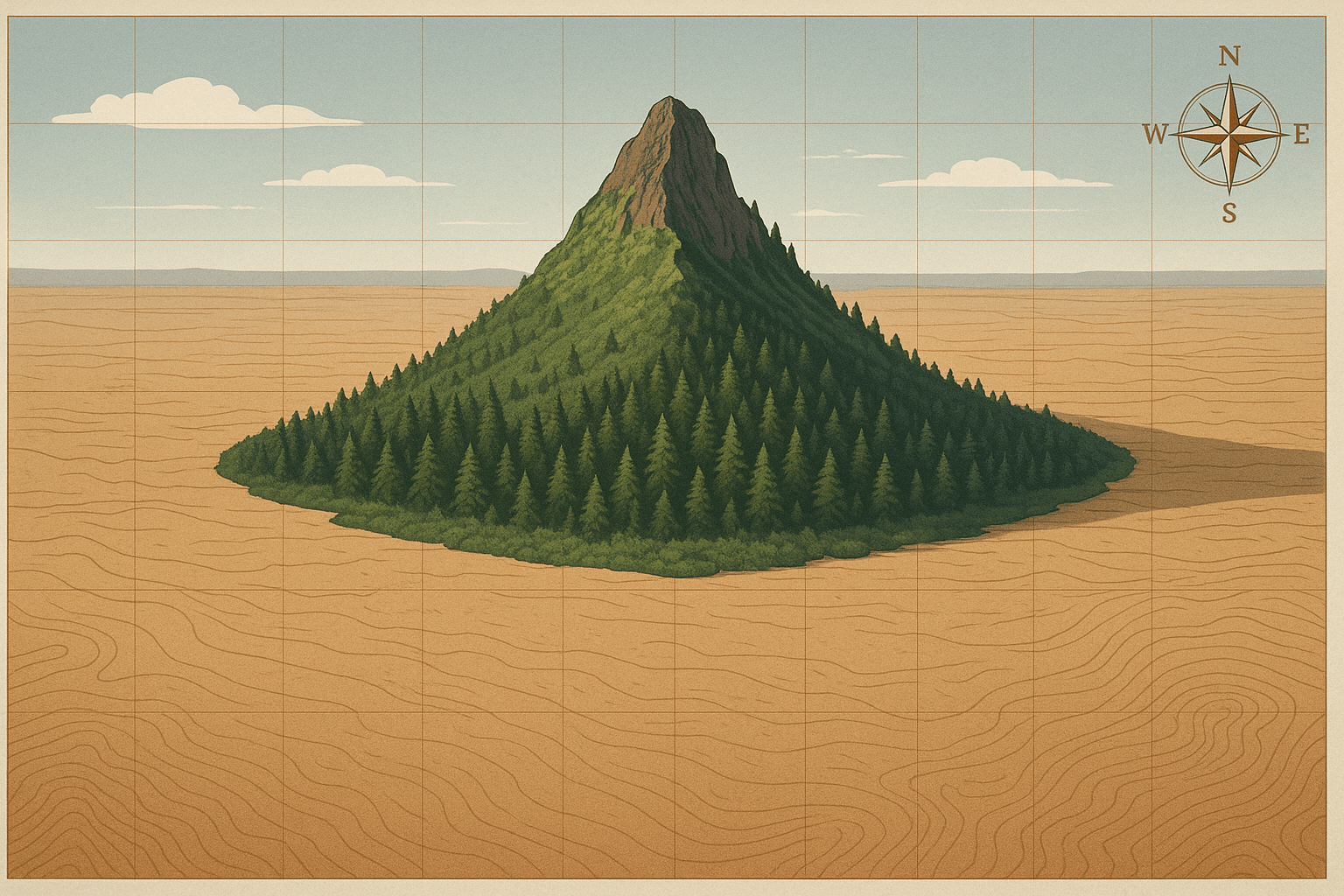

Imagine an island. Not a speck of land surrounded by ocean, but a cool, forested mountain peak rising from a sea of scorching desert. This is a “sky island”, one of the planet’s most fascinating and fragile geographical phenomena. These isolated mountains, surrounded by radically different lowland environments, are not just geological curiosities; they are living laboratories of evolution, cradles of biodiversity, and hotspots for species found nowhere else on Earth.

What Exactly Makes a Mountain a “Sky Island”?

The term “sky island” perfectly captures the essence of this landform. The “island” is the mountain itself, specifically its higher, cooler, and wetter elevations. The “sea” is the vast, often hostile, lowland environment that surrounds it—think of the Sonoran Desert in North America or the savannas of East Africa. For a species adapted to the cool pine-oak woodlands of the mountain summit, the journey across the blistering desert floor to another mountain is as impossible as a land tortoise swimming across the Pacific.

This isolation is the key ingredient, but the story of their creation is rooted in deep time, specifically the climate shifts of the Pleistocene Epoch. During the ice ages, the global climate was cooler and wetter. Forests and woodlands, which are now confined to the mountaintops, spread across the lowlands, creating continuous habitat that connected distant mountain ranges. Animals and plants could move freely between them.

As the ice retreated and the climate warmed and dried, these forests began to shrink. They receded up the slopes of the mountains, chasing the cooler temperatures. The lowlands transformed into deserts or dry grasslands, creating an impassable barrier. The populations of plants and animals that retreated upward became stranded on these newly formed “islands”, cut off from their relatives on neighboring peaks. They were left in isolation, a biological ark floating in a sea of desert.

A Global Tour of Iconic Sky Islands

Sky islands are found across the globe, each with its own unique character and collection of life. Here are a few of the most remarkable examples:

- The Madrean Sky Islands (North America): Spanning southeastern Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, and northern Mexico, this archipelago of over 40 mountain ranges rises dramatically from the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts. Mountains like the Chiricahuas and Santa Catalinas are a biological crossroads. Here, species from the Rocky Mountains (like Douglas firs) meet species from Mexico’s Sierra Madre (like Apache pines and elegant trogons). This mixing, followed by isolation, has led to incredible biodiversity, including unique, endemic species like the Mount Graham red squirrel, which exists only on a single sky island, Mount Graham.

- The Eastern Arc Mountains (Tanzania and Kenya): Often called the “Galapagos of Africa”, this chain of 13 ancient, forest-clad mountains is a world-renowned hotspot of endemism. Surrounded by arid savanna, these mountains have been isolated for tens of millions of years, allowing evolution to run wild. They are the original home of the African violet and host an astonishing number of species found nowhere else, including dozens of unique chameleon, frog, and bird species. The Udzungwa Mountains National Park, for example, protects primates like the Sanje mangabey and the Iringa red colobus, both endemic to the region.

- The Tepuis of the Guiana Highlands (South America): Perhaps the most visually stunning sky islands, the tepuis of Venezuela and Guyana are massive, sheer-sided, flat-topped mountains immortalized in pop culture by the movie Up. Rising thousands of feet above the Amazon rainforest, their summits are a world apart. The extreme isolation, poor nutrient soil, and harsh conditions on top have created bizarre and unique ecosystems. Here you’ll find carnivorous pitcher plants, ancient plant lineages, and unique frog species that have evolved in complete isolation for millions of years.

Islands of Evolution: How New Species Emerge

The isolation of sky islands makes them perfect natural experiments in a process called allopatric speciation. This is the primary way new species are formed. Here’s how it works:

- Geographic Separation: A single, widespread population gets broken up into two or more smaller, isolated populations (as happened when the forests retreated up the mountains).

- Divergence: Once separated, these populations can no longer interbreed. Each group begins to evolve independently. This divergence is driven by several factors:

- Natural Selection: The environment on each sky island is slightly different. One might be wetter, another might have different predators. Each population adapts to its own unique local conditions.

- Genetic Drift: In small populations, random chance plays a larger role in which genetic traits get passed on. Over many generations, this can cause two populations to become significantly different by chance alone.

- Reproductive Isolation: After enough time has passed—thousands or millions of years—the separated populations become so genetically different that even if they were to come back into contact, they could no longer interbreed to produce viable offspring. At this point, they have become distinct species.

Many sky island species are also considered “relicts”—remnants of populations that were once widespread during the cooler Pleistocene but now survive only in these high-elevation refuges.

A Fragile Future: Human Geography and Conservation

Despite their remoteness, sky islands are not immune to human impact. In fact, their isolation and unique nature make them exceptionally vulnerable. The most pressing threat is climate change. As global temperatures rise, the distinct climate zones on a mountain shift upwards. For a species living near the summit, there is nowhere left to go. They face being “pushed off the top” into extinction.

Other significant threats include:

- Habitat destruction from logging, mining, and development on the mountain slopes.

- Altered fire regimes, often from human fire suppression or ignition, which can devastate ecosystems not adapted to frequent or intense fires.

- Invasive species introduced by humans that can outcompete or prey on the highly specialized native life.

Recognizing their immense biological value, conservationists and scientists are working to protect these fragile realms. Establishing national parks, creating biological corridors to potentially reconnect isolated populations, and conducting critical research are all essential steps. These mountains are more than just beautiful landscapes; they are irreplaceable archives of Earth’s climatic history and dynamic theaters of evolution in action. To lose them would be to erase millions of years of unique natural history forever.