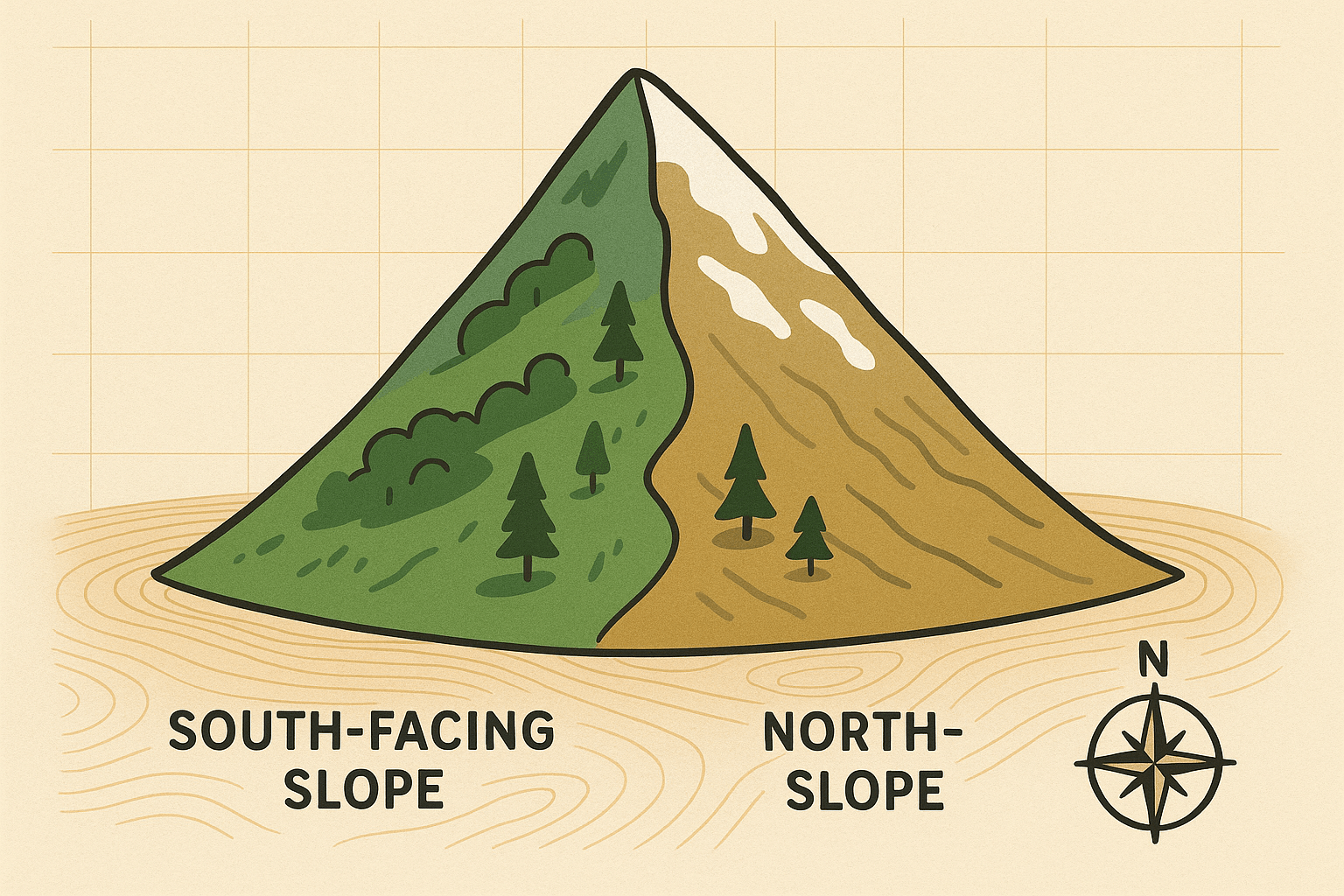

Imagine standing on a mountain ridge in the heart of the Rockies. To your left, the slope plunges downwards, covered in a dense, dark forest of fir and spruce, with damp earth and deep snow still clinging to the shadows. To your right, the mountainside is a completely different world: a sun-drenched expanse of open grassland, scattered Ponderosa pines, and dry, rocky soil. It’s as if an invisible line has been drawn down the ridgeline, separating two distinct ecosystems.

This dramatic contrast isn’t magic; it’s geography. The secret lies in a simple yet powerful concept that shapes landscapes worldwide: slope aspect.

What Exactly is Slope Aspect?

In the simplest terms, slope aspect is the compass direction that a slope faces. Is the hillside oriented towards the north, south, east, or west? This seemingly minor detail is one of the most significant factors in microclimate and ecology, dictating how much sunlight a piece of land receives throughout the day and the year.

Think of a mountain as a giant, fixed solar panel. Some parts are angled directly towards the sun, while others are angled away, living mostly in shadow. This difference in solar energy—what geographers call insolation—is the engine that drives a cascade of environmental effects, creating the mountain’s “two faces.”

The Sun is the Engine: A Tale of Two Hemispheres

The fundamental driver of aspect’s influence is the sun’s path across the sky.

- In the Northern Hemisphere (e.g., North America, Europe, Asia), the sun travels along a southern arc. This means that south-facing slopes are positioned to receive direct, intense sunlight for most of the day. North-facing slopes, in contrast, receive only indirect, low-angle sunlight, and in winter, they may get no direct sun at all.

- In the Southern Hemisphere (e.g., Australia, southern South America, New Zealand), the situation is reversed. The sun travels along a northern arc, so it’s the north-facing slopes that are the sun-basked, warmer ones, while south-facing slopes are cooler and shadier.

East- and west-facing slopes present their own unique conditions. East-facing slopes get direct sun in the morning when temperatures are cooler, while west-facing slopes bear the brunt of the hot afternoon sun, often making them the hottest and driest of all, especially in arid climates.

The Ecological Divide: From Sunbeams to Forests

This differential heating creates two vastly different microclimates, which in turn support entirely different communities of plants and animals.

Temperature and Moisture

The most immediate effect of aspect is on temperature and moisture. A slope that faces the sun is called a xeric slope. It’s hotter and, crucially, drier. The intense sun evaporates water from the soil and plants more quickly. Snow melts earlier in the spring and disappears faster after a storm.

Conversely, a slope that faces away from the sun is a mesic slope. It’s cooler and retains significantly more moisture. The soil stays damp longer, and the snowpack is deeper and can persist late into the spring or even early summer. This creates a refuge for species that can’t tolerate heat and drought.

Vegetation: The Visible Difference

Nowhere is the effect of aspect more visible than in the plant life. The contrasting conditions cultivate completely different floral communities on opposite sides of the same ridge.

On the sunny, xeric slope (e.g., south-facing in Colorado):

- You’ll find drought-tolerant grasses, hardy shrubs like sagebrush and mountain mahogany, and open woodlands.

- Trees are often species adapted to dry conditions, such as Ponderosa pine or juniper, which have deep taproots and thick bark to resist fire.

- The overall landscape feels open, bright, and arid.

On the shady, mesic slope (e.g., north-facing in Colorado):

- The environment supports a dense, moisture-loving forest.

- Trees like Douglas fir, Engelmann spruce, and aspen dominate, creating a thick canopy that further shades the forest floor.

- The understory is lush with mosses, ferns, and wildflowers that thrive in the cool, damp conditions.

- The treeline—the upper limit of tree growth—is often higher on the warmer, sun-facing slopes.

Beyond Nature: The Human Connection

For millennia, humans have intuitively understood and utilized slope aspect. This geographical knowledge is woven into our culture, agriculture, and even how we build our cities.

- Agriculture: This is perhaps the most classic example. European winemakers have long prized south-facing slopes for their vineyards, as the extra sun and warmth help ripen grapes to perfection. In the Southern Hemisphere, the best vineyards in Chile and Argentina are often found on north-facing slopes.

- Ski Resorts: Ever wonder why your favorite ski run stays snowy so long? It’s likely on a north-facing slope. Ski area developers specifically design their trail systems to place beginner and expert runs on slopes that hold snow the longest, extending the ski season.

- Housing and Settlement: In cold climates, building a house on a south-facing slope (in the NH) can significantly reduce heating costs by maximizing passive solar gain. Ancient peoples, like the Ancestral Puebloans of the American Southwest, famously built their cliff dwellings (like those at Mesa Verde) in south-facing alcoves to capture the winter sun’s warmth and be shaded from the high summer sun.

- Wildfire Management: Firefighters know that fires behave very differently depending on aspect. A fire moving up a dry, grassy south-facing slope can spread with terrifying speed. North-facing slopes, with their higher moisture content, may slow a fire’s advance or resist ignition altogether.

A World of Two Faces

Slope aspect is a beautiful illustration of how a single geographical variable can create a cascade of consequences, shaping everything from the soil beneath our feet to the patterns of global commerce. It’s a reminder that a mountain is not a uniform monolith but a complex mosaic of micro-environments.

So the next time you’re driving through a mountain range, hiking a trail, or even just looking at a photograph, pay attention to the slopes. Notice the subtle—and sometimes stark—differences from one side of a valley to the other. You’ll be seeing the mountain’s two faces, a silent, powerful testament to the dance between the Earth and the sun.