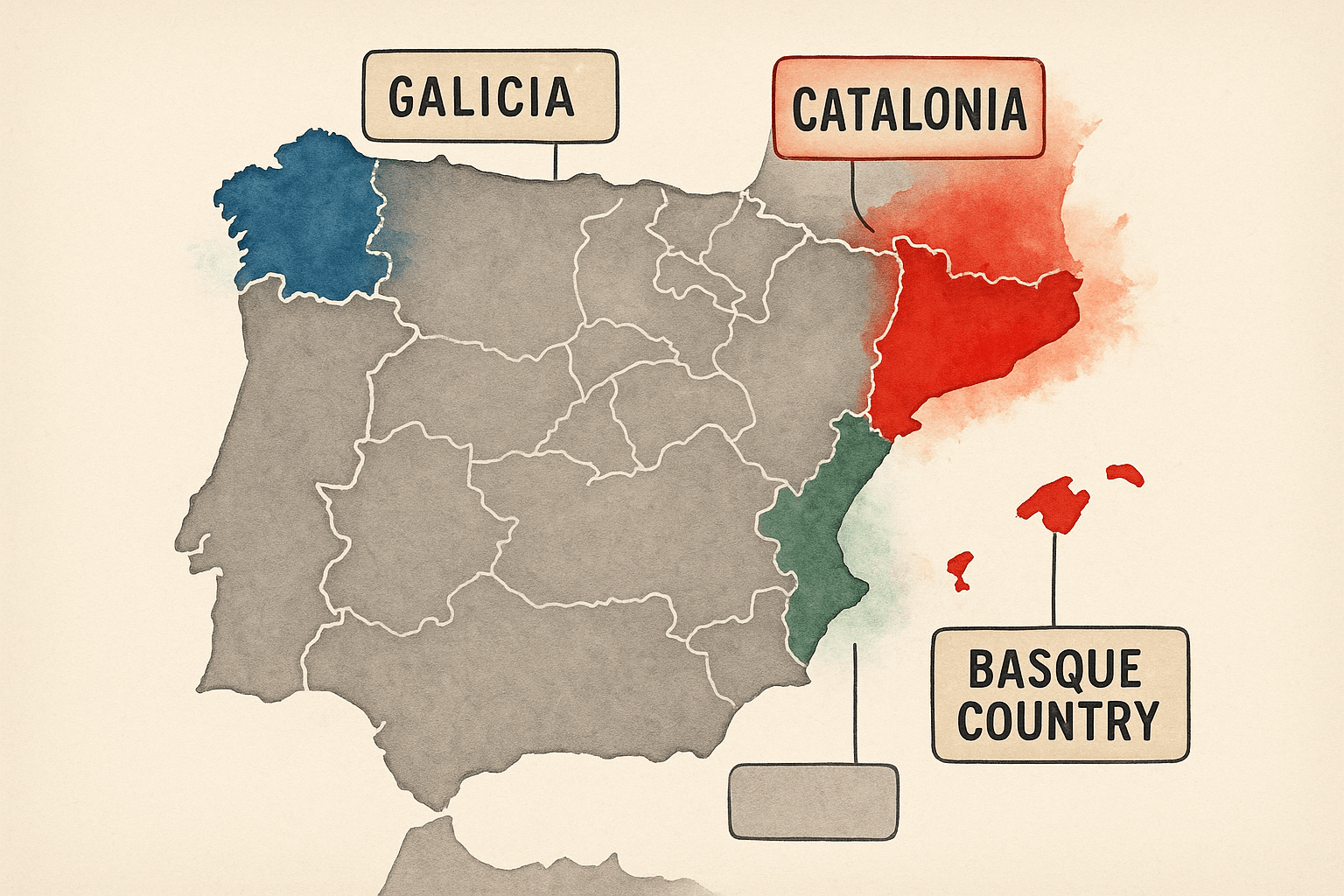

When you picture Spain, you might conjure images of flamenco dancers, sun-drenched beaches, and the distinct, rapid cadence of the Spanish language. But to stop there is to see only a fraction of the picture. Spain is not a linguistically monolithic nation; it is a vibrant mosaic of languages and cultures, a reality enshrined in a unique legal geography known as the Linguistic Statute. This framework, born from the Spanish Constitution of 1978, decentralizes language rights, creating distinct administrative, educational, and cultural landscapes across the country.

A journey through Spain isn’t just a trip through different climates and topographies; it’s an immersion into different linguistic worlds. The road signs change, the language of the classroom shifts, and the local news is broadcast in tongues that predate the modern state itself. This is the story of how Spain maps its identity, not just in soil, but in speech.

The Constitutional Bedrock: A Plurilingual State

To understand Spain’s linguistic geography, one must start with its legal foundation: the 1978 Constitution, drafted after the fall of Francisco Franco’s highly centralized and repressive regime. Franco had brutally suppressed regional languages, viewing them as a threat to national unity. The new democratic constitution took the opposite approach.

Article 3 is the linchpin. It establishes Castilian (castellano)—what the world knows as Spanish—as the official language of the state, which all Spaniards have a duty to know and a right to use. However, it critically adds that “the other Spanish languages shall also be official in the respective Autonomous Communities in accordance with their Statutes.”

This single clause cracked open the door for a profound remapping of Spain. It created a legal framework where regions could elevate their historical languages to co-official status, giving them equal footing with Spanish in law, government, and education within their borders. The result is not one Spain, but a Spain of many “linguistic countries.”

The Catalan-Speaking Lands: A Mediterranean Identity

Travel to Spain’s northeast, to the bustling region of Catalonia, with Barcelona as its heart. Here, the linguistic landscape changes dramatically. You are now in the domain of Catalan. Co-official in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, and the Valencian Community (where it is officially called Valencian), Catalan is a Romance language with over 10 million speakers.

Education as a Cornerstone

Perhaps the most potent example of the linguistic statute in action is Catalonia’s educational system. The model of “linguistic immersion” (immersió lingüística) makes Catalan the primary language of instruction in public schools. From math to history, subjects are taught in Catalan, with Spanish treated as a separate language class. The goal is to ensure all students are fully bilingual by the time they graduate, preserving Catalan as the living, working language of the next generation. This has been a source of both immense regional pride and ongoing political friction with the central government in Madrid.

A Public Sphere in Two Tongues

The co-official status is visible everywhere. A street sign will read Carrer de Gràcia followed by its Spanish equivalent, Calle de Gracia. Public institutions, from local councils to hospitals, are required to serve citizens in either language. The region boasts its own powerful public media corporation, with television channels like TV3 and Catalunya Ràdio broadcasting exclusively in Catalan, shaping a distinct cultural and political discourse.

The Basque Country: A Language Isolate in the Pyrenees

Venture west into the green, mountainous terrain of the Basque Country (Euskadi) and Navarre, and you’ll encounter a language that is a true geographical and linguistic anomaly: Basque, or Euskara. Unrelated to any other known language in the world, Euskara is a pre-Indo-European tongue that has survived for millennia, sheltered in part by the rugged geography of the Pyrenees.

A Statute of Survival and Revival

After being pushed to the brink of extinction under Franco, Euskara has undergone a remarkable revival, thanks to its co-official status. The Basque Statute of Autonomy established it as the region’s own language. The situation in neighboring Navarre is even more geographically specific, with the Foral Law on Basque dividing the region into three distinct linguistic zones:

- The Basque-speaking zone in the north, where Basque has full co-official status.

- The mixed zone, including the capital Pamplona, where its use is recognized and promoted.

- The non-Basque-speaking zone in the south, where Spanish is the sole official language.

This tiered system is a perfect illustration of legal geography—where rights and recognition are literally drawn onto the map.

Models of Bilingual Education

Unlike Catalonia’s single immersion model, the Basque education system offers parents a choice between different models (A, B, and D), which provide varying degrees of instruction in Basque and Spanish. This has been instrumental in creating a new generation of Basque speakers, pulling the language back from the precipice.

Galicia: The Atlantic Tongue

In Spain’s northwestern corner, the lush and rainy region of Galicia, another language thrives: Galician (Galego). A Romance language, Galego is so closely related to Portuguese that they were, until the late Middle Ages, considered the same language. This shared heritage gives Galicia a unique Atlantic-facing cultural geography, connecting it deeply to Portugal and the wider Lusophone world.

The Galician Statute of Autonomy makes Galego co-official, and it is a visible part of life. You’ll see it on signs for the famous pilgrimage city, Santiago de Compostela, and hear it on the regional broadcaster, TVG. The educational system is bilingual, though critics often argue that Spanish maintains a more dominant position in practice compared to the models in Catalonia and the Basque Country. Nonetheless, the statute ensures that Galego remains the language of regional identity, literature, and administration.

A Patchwork Nation

This linguistic geography isn’t limited to the “big three.” Other regions have secured lesser, but still significant, recognition for their historical languages. Asturian (Bable) in Asturias and Aragonese in Aragon are protected and promoted, though they lack the full co-official status of Catalan, Basque, or Galician. Each statute adds another thread to Spain’s complex linguistic tapestry.

What emerges is a picture of a state that is profoundly diverse. The linguistic statute is far more than a legal text; it is a map of identity, history, and political tension. It underpins the very structure of the modern Spanish state, empowering regions to protect and cultivate their unique cultural heritage. While it can be a source of political conflict, it is also the framework that allows Spain to be, officially and existentially, a nation of nations. A journey from the heart of Castile to the Catalan coast or the Basque mountains is a powerful reminder that in Spain, geography is written in more than one language.