An Ingenious Answer to a Geographical Reality

To understand the stepwell, one must first understand the geography of India, particularly its dramatic climate. Large parts of the country, especially in the west and north like Rajasthan and Gujarat, are arid or semi-arid. Life here is dictated by a single, powerful geographical phenomenon: the monsoon. For a few months of the year, torrential rains lash the landscape, filling rivers and recharging the earth. For the rest of the year, an intense, dry heat bakes the land, causing water levels to plummet.

This “feast or famine” water cycle presented a fundamental problem for ancient communities. A simple well, dug to the water table’s high point during the monsoon, would become useless as the water receded during the long dry season. How could people access the life-giving water when it was fifty, sixty, or even a hundred feet below ground?

The stepwell—known as a baori or baoli in the north and a vav in Gujarat—was the ingenious solution. Instead of just digging a shaft and lowering a bucket, engineers and architects excavated a massive, deep trench and lined its sides with intricate staircases. This allowed people to physically walk down to the water’s edge, no matter the season. As the water table dropped, more steps were revealed, ensuring year-round access. It was a dynamic architectural form designed to interact directly with the fluctuating geography of the water table.

A Symphony of Stone and Geometry

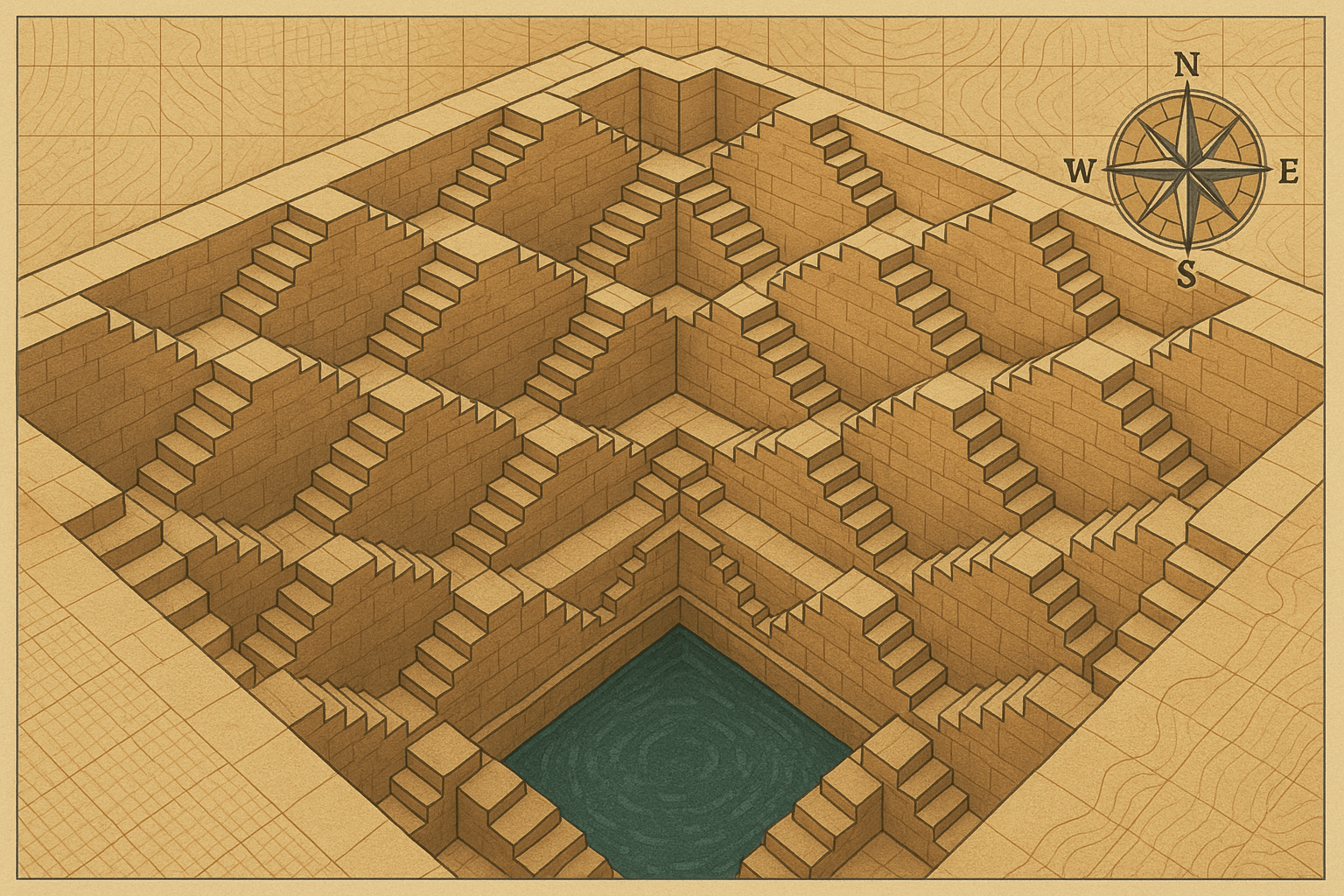

While born of necessity, stepwells evolved into extraordinary works of art. They are essentially inverted pyramids or temples, burrowing deep into the ground. Their design is a masterclass in precision, symmetry, and architectural grandeur, turning a utilitarian structure into a subterranean palace.

The visual language of stepwells is dominated by geometry. The steps are rarely simple, straight flights. Instead, they form complex, interlocking triangular patterns that crisscross down the sides of the well shaft, creating mesmerizing visual effects of light and shadow. This design wasn’t just for aesthetics; the multitude of steps distributed the load of crowds and provided multiple points of access.

Chand Baori, Rajasthan: A Geometric Marvel

Perhaps the most famous and visually stunning example is Chand Baori in the village of Abhaneri, Rajasthan. Dating back to the 9th century, it is one of the deepest and largest stepwells in the world. It plunges over 100 feet into the earth with 13 distinct levels. Its walls are lined with 3,500 perfectly symmetrical, double-flight stairs that form a hypnotic, almost surreal geometric maze. From above, it looks like an impossible Escher drawing carved into the desert landscape, a stark and powerful testament to human ingenuity in an unforgiving environment.

Rani ki Vav, Gujarat: The Queen’s Stepwell

If Chand Baori is a monument to pure geometry, Rani ki Vav (“The Queen’s Stepwell”) in Patan, Gujarat, is a celebration of ornate art. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, this 11th-century stepwell was built not just for accessing water but as a memorial to a king. It is designed like an inverted temple, featuring seven levels of terraced pavilions and galleries adorned with over 500 major sculptures and a thousand minor ones. As you descend, you are surrounded by exquisite carvings of deities, celestial beings, and scenes from Hindu mythology. It’s an underground art gallery, a spiritual space, and a water source all in one.

Adalaj Vav, Gujarat: A Fusion of Cultures

Located near Ahmedabad, the Adalaj Vav is renowned for its intricate blend of Hindu and Islamic architectural styles. This five-story-deep stepwell is octagonal in plan and famous for its beautifully carved pillars, beams, and balconies. The cool, shaded landings provided a welcome respite from the climate and became crucial social spaces. The fusion of motifs speaks to the rich history of cultural exchange in the region, embedding human geography directly into the stone.

The Cool Heart of the Community

Stepwells were far more than just reservoirs; they were the social and spiritual hearts of their communities. In the intense heat of the Indian plains, the air at the bottom of a stepwell could be several degrees cooler than at the surface. This microclimate made them natural, air-conditioned community centers.

This is where human geography comes alive. As fetching water was traditionally the responsibility of women, stepwells became a unique social space for them. Here, they could rest, talk, and share stories away from the public gaze, creating a powerful sense of community and solidarity. The stepwell was a place of news, gossip, and ritual—a vital node in the social fabric of the village or town.

Many also held deep spiritual significance. The presence of water in an arid land was seen as a divine gift, and the wells were often consecrated and treated as sacred spaces. Shrines to various gods and goddesses are common features, and the wells were sites for religious ceremonies and festivals, blending the physical geography of water with the cultural geography of faith.

Echoes from a Bygone Era

The golden age of stepwells waned with the arrival of modern infrastructure. During the British Raj, piped water and hand pumps were introduced. The wells were deemed unhygienic and potential breeding grounds for disease. Gradually, these architectural marvels fell into disuse and neglect. Many were filled with silt and garbage, their intricate carvings left to decay, forgotten by the communities they once served.

Fortunately, in recent decades, there has been a growing appreciation for their historical and architectural importance. Many are now protected monuments, painstakingly restored and drawing tourists from around the world. But their legacy is more than just a glimpse into the past. In an age of climate change and increasing water scarcity, these ancient structures offer a profound lesson in sustainable water management. They remind us of a time when architecture, community, and the environment were deeply intertwined, working in harmony to create solutions that were as beautiful as they were practical.