The Basic Principles of a Layered World

At its heart, stratigraphy is the study of layered rocks, or strata. To decipher their stories, geologists rely on a few foundational principles, first outlined by Danish scientist Nicolas Steno in the 17th century. These concepts are elegantly simple but have profound implications.

- The Principle of Superposition: In an undisturbed sequence of rock layers, the oldest layers are at the bottom, and the youngest are at the top. It’s like a stack of old magazines in your attic—the one you tossed on last week is on top of the one from a decade ago. This simple rule is the cornerstone of relative dating in geology.

- The Principle of Original Horizontality: Sediments, like sand, mud, and organic material, are typically deposited in flat, horizontal layers under the influence of gravity. If you see rock layers that are tilted, folded, or broken, it’s a clear sign that a major geological event, like an earthquake or mountain-building, occurred after the layers were formed.

- The Principle of Lateral Continuity: Rock layers extend horizontally in all directions until they either thin out, grade into a different type of sediment, or are cut off by a valley or fault. This is why geologists can confidently match the rock layers on one side of the Grand Canyon to the corresponding layers on the other side, miles away.

These principles provide the basic grammar for reading Earth’s history, allowing us to assemble a chronological timeline of events stretching back billions of years.

Reading the Pages: What Do Rock Layers Tell Us?

With the rules established, geologists can begin the fascinating work of interpretation. A single rock layer can reveal an incredible amount about what the world was like at the moment it was formed.

What the Rocks Say

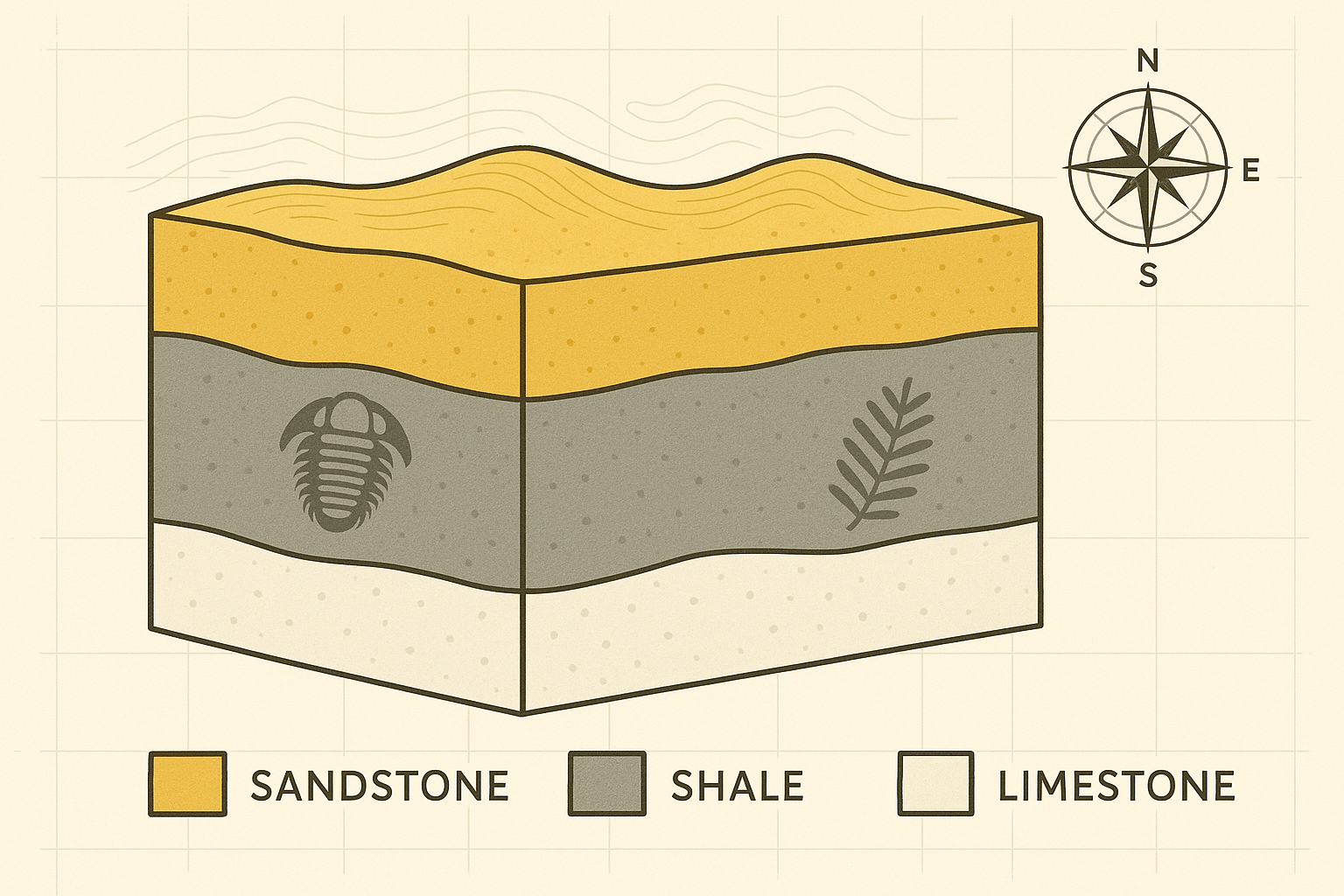

The very composition of a rock is a snapshot of an ancient environment. A thick layer of coarse sandstone, for instance, might point to a vast, windswept desert with shifting dunes, like today’s Sahara. The iconic Navajo Sandstone visible in Zion and Arches National Parks in the United States tells the story of just such a Jurassic desert. A layer of dark shale, formed from compressed mud, indicates a calm, low-energy environment like a deep lake or an ocean basin. And a layer of limestone is often the ghost of a warm, shallow tropical sea, built from the skeletons of countless marine organisms.

Clues from Ancient Life

Embedded within these layers are fossils, the preserved remains of ancient life. This is where stratigraphy gets truly exciting, blending with paleontology in a sub-discipline called biostratigraphy. Fossils are not just curiosities; they are time markers.

Certain species, known as index fossils, lived for a very short period but were geographically widespread. When a geologist finds a specific type of trilobite or ammonite in a rock layer in Morocco, they know that layer is the same age as a layer containing the same fossil in Canada. This allows for precise correlation of rocks across continents.

More dramatically, stratigraphy reveals the great dramas of life on Earth, including mass extinctions. The most famous example is the K-Pg (Cretaceous-Paleogene) boundary. All over the world, this specific stratigraphic layer, dating to 66 million years ago, marks the abrupt disappearance of dinosaur fossils. The layer itself is often enriched with the element iridium—rare on Earth’s surface but common in asteroids. This thin band of rock is the geological scar of the asteroid impact that ended the age of dinosaurs.

A Global Landmark: The Grand Canyon’s Epic Tale

There is perhaps no better place on Earth to appreciate stratigraphy than the Grand Canyon. Its exposed walls offer a clear and breathtaking cross-section of nearly two billion years of geologic time. A journey from the rim to the Colorado River is a journey backward through time.

At the top, the Kaibab Limestone (270 million years old) contains fossils of sponges and brachiopods, revealing a time when Arizona was covered by a warm, shallow sea. Descending further, you encounter the Coconino Sandstone, whose cross-bedded patterns are the fossilized remnants of massive coastal sand dunes. Deeper still, the distinct, cliff-forming Redwall Limestone tells of a deeper marine environment. Finally, at the very bottom, in the Inner Gorge, you find the dark, twisted Vishnu Schist. At 1.75 billion years old, these are the metamorphic roots of ancient mountains, a world that existed long before complex life crawled onto land.

Stratigraphy in the Human World

Stratigraphy isn’t just an academic pursuit for understanding the distant past; it has profound and practical applications in the modern world, bridging physical and human geography.

From Natural Resources to Ancient Cities

The global economy runs on energy and resources found using stratigraphic principles. Oil and natural gas are trapped in porous rock layers that are capped by impermeable ones. Geologists use stratigraphy to map these underground structures and predict where to drill. The world’s great coal seams are simply thick stratigraphic layers of fossilized swamp plants from the Carboniferous Period.

Even our access to water depends on it. Aquifers, the underground layers of rock that hold groundwater, are mapped using stratigraphic analysis to ensure sustainable water supplies for cities and agriculture.

The connection extends directly to human history. Archaeologists use the exact same principles of superposition to excavate ancient settlements. At a “tell”—a mound formed by centuries of rebuilding—the deepest layers contain the oldest artifacts, allowing researchers to piece together the history of a city or culture. From the ruins of Troy in Turkey to the ancient pueblos of the American Southwest, stratigraphy provides the timeline for human civilization.

The next time you see a road cutting through a hillside, exposing layers of earth and rock, take a moment to look closer. You are seeing Earth’s library with its pages open for all to see. Each band of color and texture is a chapter in a story that includes rising mountains, advancing seas, evolving life, and catastrophic impacts. Stratigraphy gives us the literacy to read that story, connecting us to the immense and awe-inspiring history of the ground right under our feet.