The Vertical Frontier: Defining the Split Estate

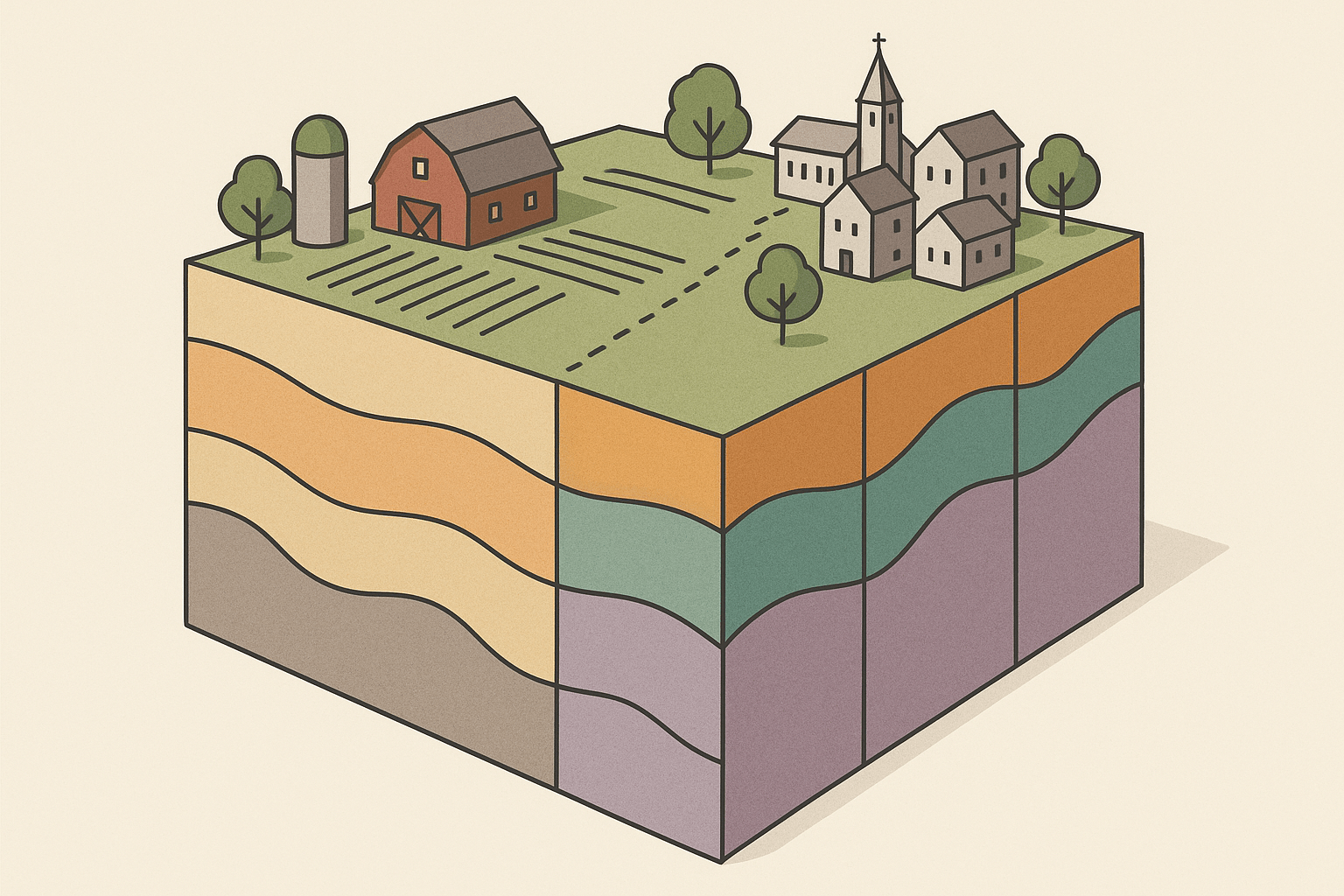

In many parts of the world, particularly the United States, what you own on the surface isn’t necessarily what you own underneath. This legal concept is known as a “split estate”, where the rights to the surface (for farming, building, living) are severed from the rights to the “mineral estate” below. The mineral estate can include a vast array of resources: oil, natural gas, coal, uranium, gold, salt, and even geothermal steam.

The core of the conflict often stems from a legal principle known as the “dominant mineral estate.” In the U.S., the law generally views the mineral estate as dominant over the surface estate. This means the owner of the subsurface rights has the legal right to use the surface in any “reasonable” way to access and extract their resources. Imagine owning a peaceful farm, only to discover that an energy company that owns the mineral rights beneath you has the authority to build an access road across your fields, erect a drilling rig near your barn, and lay a pipeline through your pasture. Your consent is often not required.

This upends the old common law idea of “Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos”—a Latin phrase meaning “whoever owns the soil, it is theirs up to Heaven and down to Hell.” In the modern world of resource extraction, ownership is rarely that simple. The “down to Hell” part has been sliced, diced, and sold off, creating a layered, and often contested, geography of ownership.

A Patchwork of Ownership: The American West as a Case Study

Nowhere is the geography of the split estate more visible than in the American West. The landscape is a complex checkerboard of private, federal, state, and tribal lands, and the ownership below ground is even more tangled. This situation is a direct legacy of 19th-century U.S. land policy.

- Homestead Acts: As the federal government encouraged settlement, it passed laws like the Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916. This act granted settlers 640-acre parcels of land suitable for grazing, but the government explicitly kept the rights to all the coal and other minerals beneath the surface.

- Railroad Grants: To spur westward expansion, the government granted vast tracts of land to railroad companies. The railroads later sold much of this land to individuals and ranchers to finance their operations, but frequently held on to the valuable mineral rights.

The result is a geographical mosaic where a single ranch in Wyoming or Colorado might have the federal government, an energy corporation, and a private family all owning different “layers” of the same piece of land. The consequences are written onto the physical landscape. The fracking boom of the 21st century has made these dormant subsurface rights incredibly valuable. Across the West, and even in more populated areas like Colorado’s Front Range, suburbs now sit uneasily beside active drilling operations. The human geography is one of friction between long-time ranchers who value the surface for their livelihood and a global energy market that values the shale formations thousands of feet below.

Global Concessions and Geopolitical Fault Lines

While the U.S. system of private mineral ownership is unique, the conflict over subsurface resources is a global phenomenon. In most other nations, the state claims ownership of all resources beneath the soil—a concept known as the Regalian doctrine. Instead of selling the rights, governments grant concessions or licenses to multinational corporations to explore and extract.

This creates a different, but equally volatile, set of geographical conflicts:

- The Niger Delta, Nigeria: The Nigerian government owns the nation’s vast oil reserves and grants concessions to global oil giants. However, local communities who live on the surface land, like the Ogoni people, have seen their farmlands and fishing waters devastated by decades of oil spills and gas flaring. They bear the environmental cost while the profits flow to the government and foreign corporations, creating a landscape of pollution, poverty, and violent conflict.

- The Amazon Rainforest: In countries like Ecuador and Brazil, government-granted mining and oil concessions frequently overlap with the legally recognized territories of Indigenous peoples. For these communities, the land is not a commodity but the basis of their culture, food, and spiritual life. The arrival of heavy machinery to extract gold or oil represents a physical and existential threat, leading to deforestation, river pollution from mercury and oil, and violent clashes on the frontiers of extraction.

- The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): The global demand for cobalt and coltan—minerals essential for our smartphones and electric vehicle batteries—fuels a brutal reality in the DRC. Government concessions for these subsurface resources are at the heart of geopolitical maneuvering and armed conflict, displacing entire communities and creating a human geography defined by instability and exploitation.

The Geography of Conflict and Coexistence

Ultimately, the legal abstraction of subsurface rights has very real physical and human consequences. The extraction of what lies below actively reshapes the surface world.

It can cause land subsidence, where the ground literally sinks as oil, gas, or water is pumped out, a phenomenon seen in California’s San Joaquin Valley. It can create entirely new, and often toxic, landforms like the mountainous piles of tailings from mines. Open-pit mines, like the Bingham Canyon Mine in Utah, are so large they are visible from space—the ultimate geographical scar left by the pursuit of subsurface wealth.

On the human side, it dictates where people can live, drives migration, and fuels the “resource curse”—the paradox that places with the greatest natural wealth are often home to the most intense poverty and conflict. Yet, it also spurs new forms of resistance and negotiation. Surface Use Agreements, Community Benefit Agreements, and international movements for Indigenous rights are all attempts to redraw the map and give surface dwellers a voice in what happens beneath their feet.

As we dig deeper for the resources to power our modern world, the question of who owns below will only become more critical. It is a reminder that every landscape has a hidden depth, and the lines drawn on the maps beneath our feet are just as important as the ones we see on the surface.