Picture a postcard from Switzerland: soaring snow-capped peaks, serene blue lakes, and impossibly green valleys dotted with charming chalets. It’s an image of peace, neutrality, and pristine nature. Yet, hidden within this idyllic landscape, blasted into the very heart of the mountains, lies the story of one of the most ambitious and geographically ingenious defense plans ever conceived: the Schweizer Réduit, or National Redoubt.

This was not a plan to defend Switzerland’s borders. It was a strategy born of desperation and resolve during the darkest days of World War II. As Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy surrounded the small alpine nation in 1940, the Swiss military, under General Henri Guisan, made a stark calculation. They could not hope to defend the entire country, especially the flat, populous, and industrial Central Plateau (Mittelland). Instead, they would cede the lowlands and retreat into a massively fortified, self-sufficient core in the high Alps. The goal was simple and brutal: make an invasion so costly, so time-consuming, and so strategically pointless that no aggressor would deem it worthwhile.

The Alps as the Ultimate Fortress

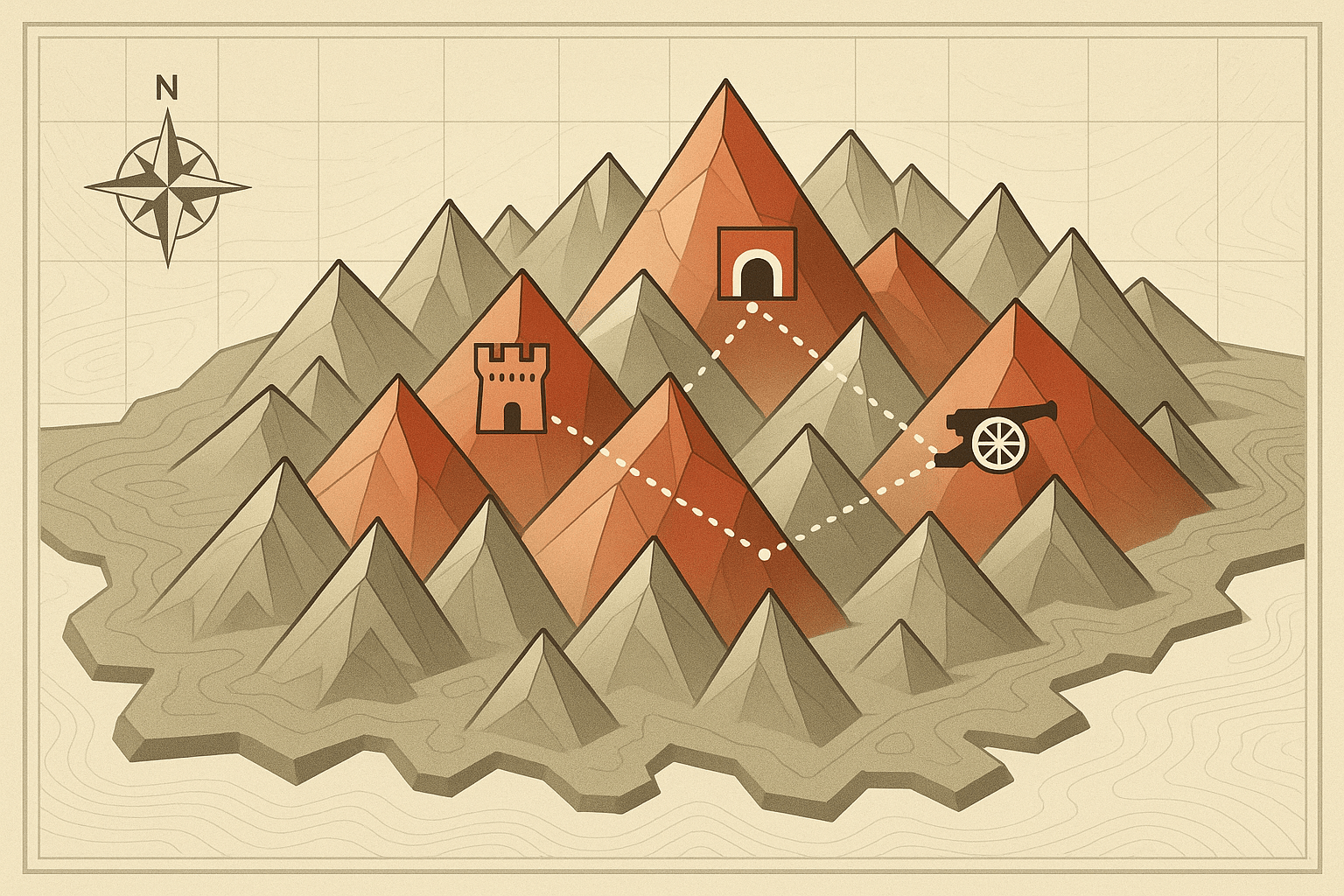

The entire concept of the National Redoubt is a masterclass in military geography. The plan leveraged Switzerland’s most defining physical feature—the Alps—as its primary defensive asset. The Alps are not just tall; they are a tangled, formidable barrier of rock and ice, sliced by deep valleys and connected by a mere handful of high, narrow passes.

The Redoubt’s architects saw these geographical features as natural kill zones. An invading army, with its tanks and heavy equipment, could not simply spread out. It would be forced into predictable, narrow corridors, such as:

- The Gotthard Pass: The crucial north-south artery, controlling access between Germany and Italy.

- The Furka and Grimsel Passes: A high-altitude nexus connecting the Rhône and Rhine valleys.

- The Saint-Maurice Gorge: A narrow chokepoint in the Rhône valley in the west, guarding access from France.

By concentrating their forces within this mountainous core, the Swiss army could use the terrain to its advantage. A small number of well-positioned defenders could hold off a much larger attacking force, raining down fire from fortified positions high above the valley floors. The geography itself would become a weapon, funneling the enemy into pre-sighted artillery and machine-gun emplacements.

Engineering the Landscape: Bunkers, Tunnels, and Traps

If the Alps provided the foundation, Swiss engineering provided the teeth. From the 1930s through the Cold War, a colossal and secretive construction project transformed the mountains. This was human geography writ large, directly shaping the landscape for a military purpose.

The most iconic elements are the thousands of bunkers and fortifications. These were not crude concrete blocks but marvels of camouflage. Artillery bunkers were disguised as enormous boulders, their gun ports hidden by cleverly painted steel doors. Entire command posts and barracks were built behind the facade of a rustic barn or a quaint chalet, complete with fake windows and curtains. From the outside, you would see a peaceful pasture; from the inside, it was a fortress ready for war.

Even more critical was the control of infrastructure. The Swiss meticulously rigged nearly every major bridge, tunnel, and mountain road with explosives. The vital trans-alpine rail tunnels, like the Gotthard and Simplon, were a key prize for the Axis powers, who needed them to move troops and supplies. Switzerland’s trump card was its credible threat to detonate charges deep within these tunnels, collapsing them and rendering them useless for years. The message was clear: “You can try to invade, but the strategic prize you seek will be destroyed the moment you cross our border.” This act of geographical denial was a powerful deterrent.

The Redoubt’s Strategic Geography

The National Redoubt was not the entire Swiss Alps, but a specific, strategically chosen area. It formed a rough triangle, anchored by three major fortress complexes:

- Fortress Sargans: In the east, guarding the Rhine valley and the border with Austria and Liechtenstein.

- Fortress Saint-Maurice: In the west, locking down the Rhône valley.

- Fortress Gotthard: The central bastion, the keystone of the entire system, controlling the vital north-south passes.

The decision to retreat here had a profound human geography consequence. It meant abandoning the Mittelland—the region between Geneva and Zurich where most Swiss people lived and where the nation’s economic heart beat. In the event of an invasion, the government, military command, and essential personnel would retreat into the Redoubt, leaving the civilian population of the lowlands to fend for themselves under enemy occupation. It was a grim strategy of national survival, prioritizing the continuity of a sovereign Swiss state over the protection of all its territory and citizens.

The Legacy Etched in Stone

The direct threat of invasion passed, but the Redoubt strategy continued as the cornerstone of Swiss defense policy throughout the Cold War. Billions of francs were invested in maintaining and upgrading this hidden mountain empire. With the end of the Cold War, however, the Redoubt’s military purpose faded.

Today, this incredible network is being repurposed in fascinating ways, a testament to Swiss ingenuity. Many of the vast, climate-controlled bunkers have been sold off. Some have been transformed into:

- Secure Data Centers: Their remote, protected nature is perfect for storing the world’s digital information.

- Luxury Hotels and Museums: The Sasso San Gottardo museum, located in a former artillery fortress on the Gotthard Pass, allows visitors to walk through the once-secret corridors.

- Cheese-Aging Cellars and Mushroom Farms: The stable temperature and humidity inside a mountain are ideal for artisanal food production.

The National Redoubt has left an indelible mark on the Swiss psyche and landscape. It cemented an identity of self-reliance, armed neutrality, and meticulous preparation. It explains the nation’s system of militia-based civil defense and the old joke that the Swiss don’t have an army, they are an army.

So the next time you see a picture of a tranquil Swiss mountain, look a little closer. The landscape is not just a product of geological forces. It is a historical document, a carefully engineered fortress whose secrets are slowly being revealed—a silent, stony testament to a small nation’s unyielding will to remain free.