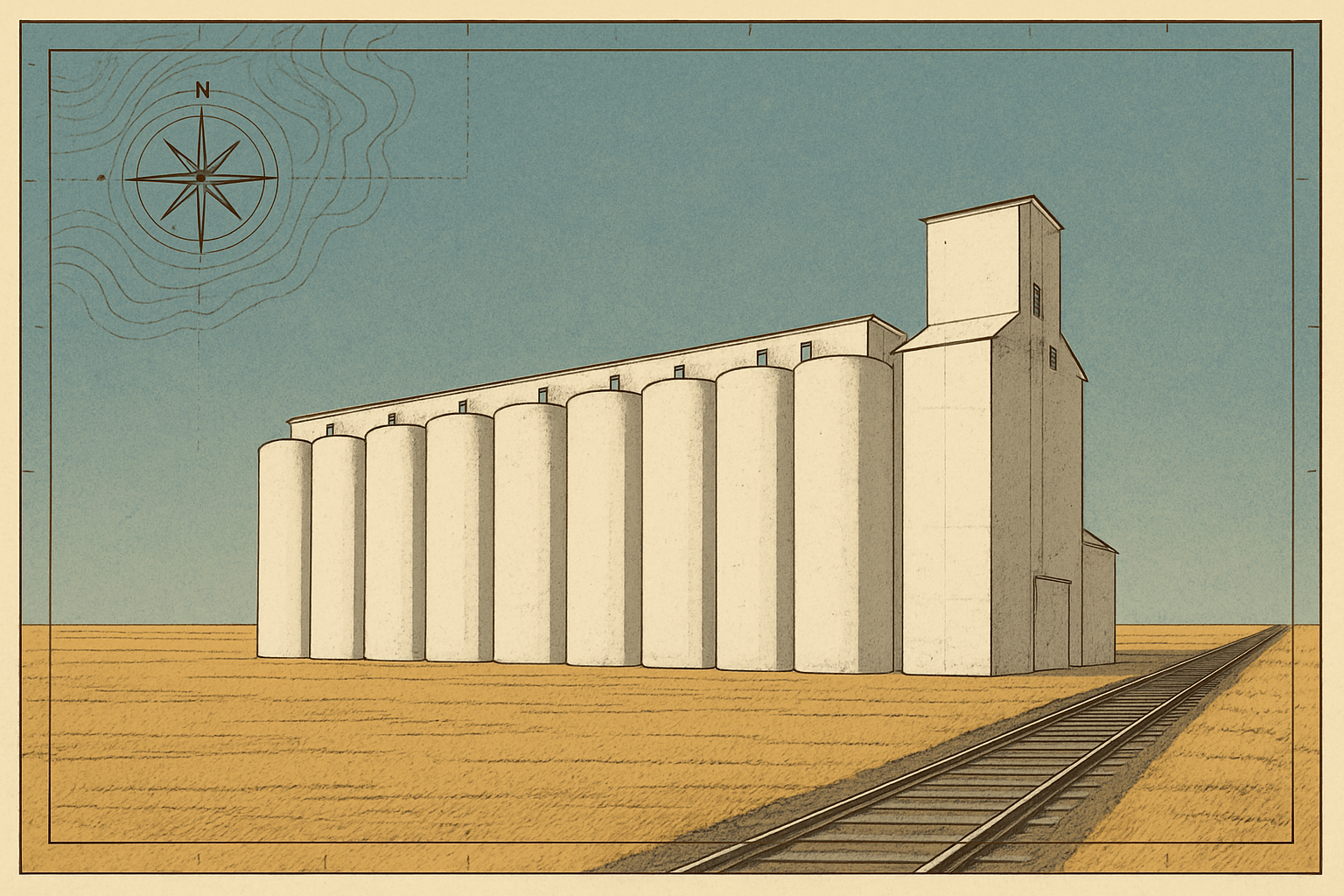

Travel across the vast, flat heartlands of North America, the Pampas of Argentina, or the Wheatbelt of Australia, and you will inevitably be greeted by the same stoic silhouette. Long before you see the town, you see the elevator. These towering structures, often clad in weathered wood or stark concrete, rise from the horizon like man-made mountain peaks. They are the “cathedrals of the prairie”, functional monuments that are as central to the geography and identity of these regions as any river or mountain range.

But what exactly are these prairie skyscrapers? To understand their architecture is to understand the flow of food across the globe, the history of settlement, and the profound relationship between humanity and the land.

The Anatomy of a Prairie Giant

At its core, a grain elevator is a machine for moving grain vertically—hence the name “elevator”—to overcome gravity and allow for efficient storage and distribution. While designs have evolved, the fundamental components, dictated by function, have remained remarkably consistent. Think of it as a vertical factory for grain handling.

- The Receiving Pit: The journey begins here, in a grate-covered pit at the base where trucks or wagons dump their harvested grain.

- The Leg: This is the elevator’s heart. It’s a continuous belt studded with buckets or cups running inside a vertical shaft. The leg scoops grain from the pit (called the “boot”) and carries it to the very top of the structure.

- The Headhouse: The highest enclosed part of the elevator, housing the top of the leg and the “distributor.” This machinery is the brain of the operation.

- The Distributor: A spout that can be rotated to direct the flow of grain from the leg into any one of the storage bins below.

- The Bins (or Silos): These are the main, visible storage cylinders or shafts that form the body of the elevator. Gravity is now the operator’s friend, holding the grain until it’s needed.

- The Loading Spout: When it’s time to ship, gates at the bottom of the bins are opened, and grain flows by gravity into a loading spout, which directs it into a waiting rail car or semi-truck.

This ingenious system, born of necessity, allowed farmers to handle massive, seasonal harvests with incredible efficiency, transforming agriculture from a local affair into a global industry.

A Geographical Imperative: Why Elevators Are Where They Are

Grain elevators are not placed randomly; their location is a masterclass in human and physical geography. They exist at the precise intersection of fertile land and transportation networks.

The world’s great grain-growing regions—the Great Plains, the Pampas, the Australian Wheatbelt—share a key geographical feature: vast, flat, and fertile alluvial plains. This physical geography is perfect for mechanized, large-scale agriculture. But fertile soil is useless without a way to get the product to market.

Enter the railroad. The expansion of rail networks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the catalyst for the grain elevator boom. Elevators were built as nodes along these steel arteries. In North America, they were often spaced every 7 to 10 miles along a rail line—a distance strategically determined by what a farmer with a horse-drawn wagon could travel to unload grain and return home in a single day. The elevator, therefore, became the essential link connecting the individual farm to the national, and eventually global, market. It consolidated countless small harvests into standardized, shippable commodities.

The Evolution of Form: From Wood Crib to Concrete Colossus

The architectural form of the grain elevator tells a story of technological change and shifting economies of scale.

The Classic Wooden Era

The most iconic elevators are the early wooden-cribbed structures that once defined thousands of prairie towns. Built from the late 1800s through the 1950s, these elevators were constructed by stacking lumber planks flat on top of each other to create the thick, strong walls of the bins. Often painted a signature “boxcar red” or stark white, they were emblazoned with the name of the town and the farmer’s cooperative that owned it. They were flammable and had limited capacity, but they were the undisputed sentinels of the rural landscape for generations.

The Age of Concrete

By the mid-20th century, concrete began to take over. Concrete elevators were fireproof, more durable, and could be built on a much grander scale. These monolithic structures, often consisting of a tight cluster of cylindrical silos, represented a new era of agricultural consolidation. Their clean lines and pure, unadorned functionalism caught the eye of European modernist architects like Le Corbusier, who famously celebrated them in his book Vers une Architecture (Toward an Architecture), calling them “the magnificent first-fruits of the new age.” He saw in their raw, engineered beauty a model for modern design.

The Modern Inland Terminal

Today, the landscape is increasingly dominated by massive inland terminals. These sprawling complexes of enormous steel and concrete silos can hold millions of bushels of grain. They are less the “cathedral” of a single town and more the industrial engine of a vast region, often located at the junction of major highways and multiple rail lines. While they lack the romantic charm of their wooden predecessors, their sheer scale is a testament to the incredible productivity of modern agriculture.

Icons of a Vanishing Geography

More than just buildings, grain elevators are profound cultural landmarks. For over a century, they have served as the geographic and social anchor of rural communities. Their verticality in an overwhelmingly horizontal world makes them an instant point of reference. They are the skyscraper of the prairie, the landmark that says “you are here”, the symbol of a town’s prosperity and reason for being.

Yet, this geography is changing. As farms have consolidated and transportation has improved, many of the smaller, historic wooden elevators have become obsolete. Every year, more of these icons are decommissioned and torn down, a process that many see as the erasure of a town’s identity. But there is also hope in reinvention. Around the world, communities are finding new life for these structures, converting them into museums, art galleries, climbing walls, and unique private homes, preserving their architectural form while giving them a new purpose.

So the next time you drive through a flat, agricultural landscape, look to the horizon. That towering silhouette is not just a silo. It is a work of functional architecture, a node in the global food web, and a powerful symbol of a place and its people—a true cathedral of the prairie.