This was the genius of the great nomadic empires of the Eurasian steppe, most famously the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan. Theirs was an architecture of motion, a system of power built not on foundations of stone, but on the rhythms of grass, wind, and horse. To understand their success is to understand a completely different form of human geography, one where the capital city could be packed up and moved in a single afternoon.

The Heart of the Empire: The Ordu

The core of nomadic political and military life was the Ordu. Often translated as “camp”, “court”, or “horde”, this term fails to capture its true significance. The Ordu was a mobile capital, a city on the move, and the physical embodiment of the Khan’s power. It was a meticulously organized settlement, a masterpiece of portable urban planning.

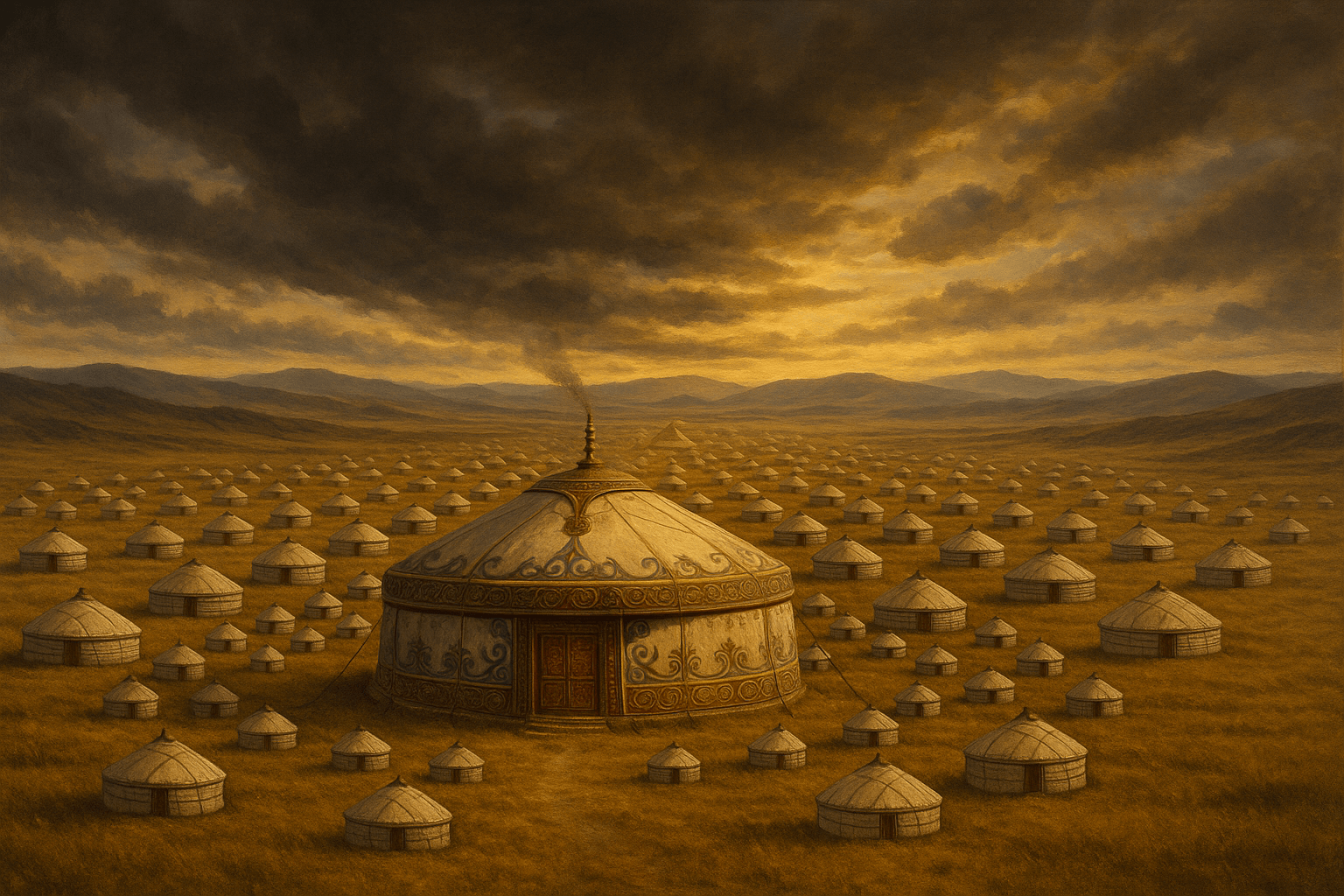

Imagine a vast collection of felt-covered dwellings, known as gers (or yurts). At the absolute center stood the Great Khan’s ger, often larger and more ornate, sometimes draped in white felt to signify its sacred status. From this central point, the rest of the camp radiated outwards in a clear hierarchy:

- Closest to the Khan were the gers of his wives, family, and closest advisors.

- Beyond them were the encampments of his generals and key administrators.

- The outermost rings were comprised of the regular soldiers and their families.

This layout was not random; it was a map of the empire’s power structure, visible to all. The position of your ger in relation to the Khan’s was a direct reflection of your status. The entire city, which could house tens of thousands of people, was oriented according to specific cosmological and practical principles, often with the entrance of each ger facing south. When the Ordu moved, this entire complex geographical arrangement was dismantled and re-established, sometimes daily, with astonishing speed and precision.

While the Mongols did eventually establish a fixed capital at Karakorum in modern-day Mongolia, the true center of gravity remained with the Khan and his traveling Ordu. Karakorum was more of a logistical and symbolic hub, a place to house foreign artisans and receive emissaries. The real decisions, the true pulse of the empire, beat on the open steppe, wherever the Khan’s ger was pitched.

Pastureland: The Strategic Fuel of Conquest

An empire on the move requires fuel, and for the Mongols, that fuel was grass. The geography of the Eurasian steppe—a vast, semi-arid grassland stretching from Manchuria to Hungary—was the ultimate source of their power. This immense sea of grass was the engine of their military machine.

Control of territory was not about owning farmland, but about commanding the best pastureland. A nomadic clan’s wealth and strength were measured not in gold, but in the size of its herds—horses, sheep, goats, and camels. Horses, in particular, were the key to military supremacy. The Mongol warrior was a centaur-like figure, capable of riding for days, eating and sleeping in the saddle. A single warrior might have a string of several horses, allowing him to switch mounts and cover vast distances without exhausting his steed.

This reliance on pasture dictated a unique rhythm of life and a profound understanding of physical geography. Nomads practiced transhumance—a seasonal migration between summer and winter pastures. This was a calculated strategy to prevent overgrazing and follow the availability of water and grass. They knew the landscape intimately: where the mountain passes were free of snow, which river valleys offered the best protection from winter winds, and where the spring grasses would sprout first. Their empire’s “architecture” was thus written on the land itself, in the seasonal paths they followed year after year.

Mastering Space: The Ultimate Weapon

The nomadic mastery of space and mobility gave them a decisive advantage over the sedentary civilizations they encountered. While empires in China, Persia, and Europe were defined by their fortified cities and fixed borders, the Mongols treated space as a fluid medium for projecting power.

Mobility as a Strategic Doctrine

Sedentary armies were slow, tied to supply lines of grain and infantry. The Mongol army, by contrast, was its own supply line. Their herds provided food (milk, meat) and transport. They could flow around fortresses, ignoring strongpoints that would have halted a traditional army. They chose their battles, striking with lightning speed from unexpected directions and vanishing back into the steppe before a response could be mustered. For their enemies, it was like fighting the wind. How do you lay siege to a capital city that has no fixed address?

The Yam: The Empire’s Nervous System

To manage their vast conquered territories, the Mongols engineered one of history’s most brilliant logistical systems: the Yam. This was a network of relay stations, set up roughly every 25-30 miles across the empire. Each station was equipped with fresh horses, food, and lodging for official messengers. A rider carrying a decree from the Khan could gallop from one station to the next, swapping for a fresh horse and continuing at full speed. This “pony express” of the steppes allowed information and orders to travel at an unprecedented rate of over 150 miles a day. It was the geographical infrastructure that bound the empire together, effectively shrinking the vast distances and allowing the Khan to administer a territory stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the Danube River.

The architecture of nomadic power challenges our very definition of civilization and empire. It was an empire whose monuments were not stone structures, but well-trodden migratory paths. Its capital was not a location, but a kinetic arrangement of people and animals. Its strength lay not in walls that kept people out, but in an infrastructure of movement that bound a continent together. By mastering the geography of the steppe, the nomads weaponized space itself, proving that the most powerful architecture is not always the one you can see, but the one that controls the world in motion.