Imagine hiking a narrow path carved into the side of a sheer alpine cliff. To one side, a dizzying drop reveals a sun-drenched valley far below. To the other, a gentle stream of crystal-clear water gurgles along in a handcrafted wooden channel, seemingly defying gravity. This is not a scene from a fantasy novel, but a very real and breathtaking experience in the Swiss canton of Valais. You are walking along a bisse, a testament to the incredible ingenuity and resilience of medieval mountain communities.

The Geographical Imperative: A Land of Thirst and Plenty

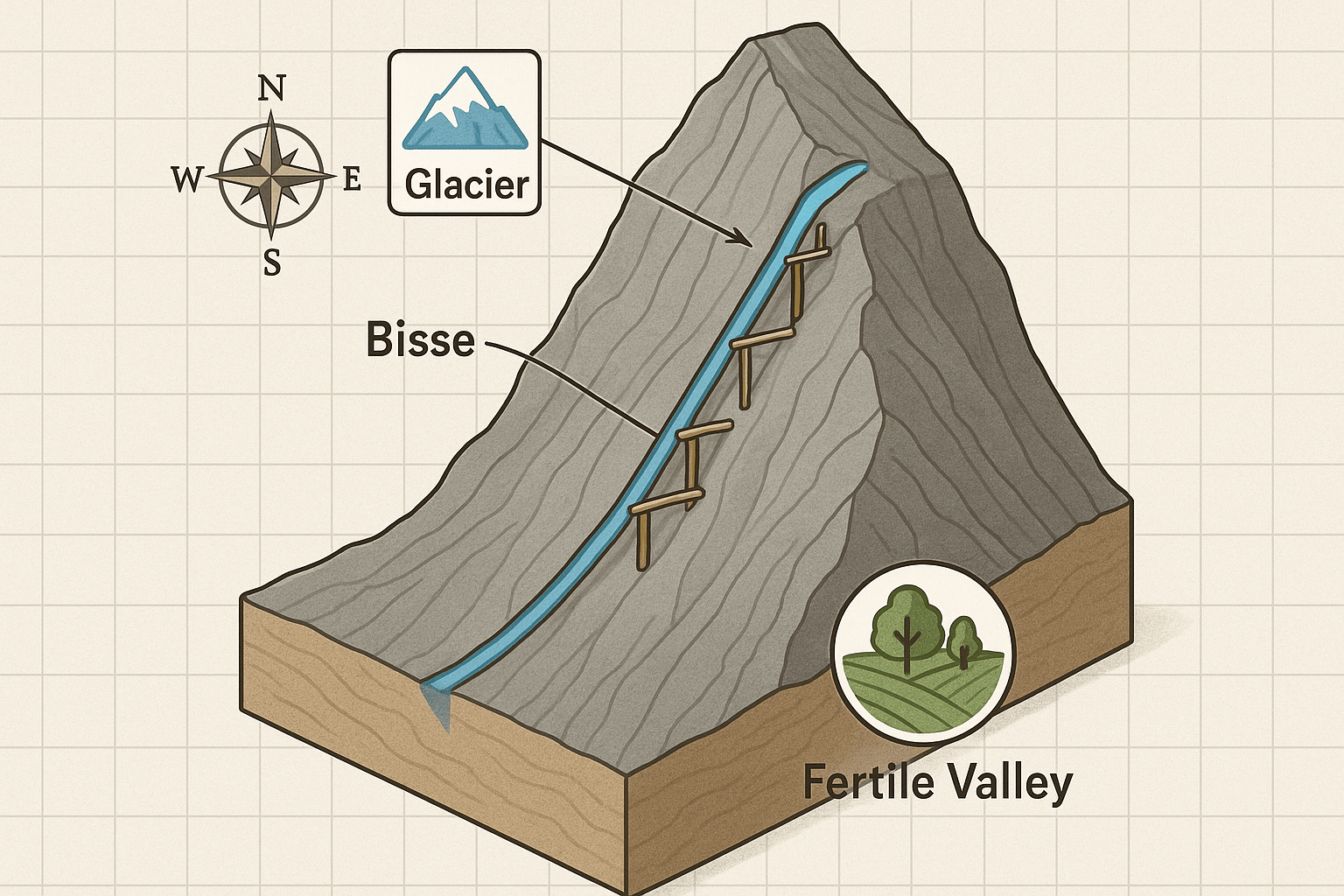

To understand the “bisses” (known as suonen in the German-speaking parts of Valais), one must first understand the unique geography of the region. The Valais is a land of dramatic contrasts. The mighty Rhône River has carved a deep, wide valley flanked by some of Europe’s highest peaks: the Matterhorn, the Dom, and the Weisshorn pierce the sky, their glaciers glistening in the sun. This towering wall of mountains, however, creates a powerful geographical phenomenon: the rain shadow effect.

As moist air masses from the west and north are forced to rise over the Bernese and Pennine Alps, they cool and release their precipitation on the outer slopes. By the time the air descends into the Rhône Valley, it is dry and warm. This makes the valley floor one of the driest and sunniest places in Switzerland, with the city of Sion receiving only about 600 mm (24 inches) of rain per year—comparable to parts of the Mediterranean.

For centuries, this created a paradox. High above, glaciers and snowfields held an almost infinite supply of water. Down below, the sun-baked terraces, ideal for farming and viticulture, were parched and barren. The challenge was monumental: how to bring the life-giving glacial meltwater down from the high altitudes to the fertile but thirsty lands below?

Daring Medieval Engineering

The answer was the bisse. Beginning as early as the 13th century, communities of farmers embarked on one of the most audacious engineering projects of the Middle Ages. With rudimentary tools—hammers, picks, and chisels—they set out to build channels that would capture water from high-altitude streams and guide it, sometimes for dozens of kilometers, to their fields.

The construction was perilous and ingenious:

- Precise Gradient: The builders had to maintain a very slight, consistent downward slope, typically between 1 and 3 percent. Too steep, and the rushing water would erode the channel; too gentle, and the water would stagnate. Without modern surveying equipment, they achieved this remarkable precision using rudimentary water levels and an intimate knowledge of the terrain.

- Carved from Rock: Where the path crossed solid rock, workers, often suspended by ropes, painstakingly chipped away at the cliff face to create a ledge for the water to flow.

- Wooden Channels: The most iconic feature of the bisses are the wooden troughs, or kännel. These were typically constructed from hollowed-out larch logs, a durable and water-resistant wood abundant in the Alps. These troughs were then mounted onto the sheerest rock faces, held in place by wooden pegs driven into cracks in the stone. Maintaining these sections was a death-defying task.

Building a bisse was a communal effort, a fight for collective survival. The results were transformative, turning arid slopes into a patchwork of lush meadows, verdant vineyards, and productive orchards famous for their apricots and apples.

The Social Fabric: Guardians of the Water

The bisses were more than just infrastructure; they were the backbone of the community’s social structure. Since water was the most precious resource, its management was strictly organized. The channels were built and owned by consortages, or cooperatives of users.

These consortages established intricate rules, known as Wässerwasser, governing the distribution of water. Each landowner had the right to a specific amount of water for a specific duration, a schedule that was meticulously followed. To enforce these rules and maintain the channel, a “gardien du bisse” (guardian of the bisse) was appointed. This was a respected and vital role. The guardian patrolled the entire length of the bisse daily, clearing debris, making repairs, and ensuring the equitable flow of water to the designated plots. This system of communal management prevented conflict and ensured the long-term survival of the entire community.

From Lifeline to Leisure: Hiking the Bisses Today

While modern irrigation techniques have replaced the function of many bisses, hundreds of kilometers of these historic waterways have been lovingly preserved. Today, their primary role has shifted from agriculture to tourism, offering some of the most unique and accessible hiking experiences in the Alps.

Because they follow a gentle gradient, the paths along the bisses are relatively flat, making them perfect for families and casual walkers. Yet, they traverse some of Switzerland’s most spectacular landscapes, offering panoramic views without the strenuous climb typically required. The constant, soothing sound of trickling water accompanies you, a reminder of the channel’s life-giving purpose.

Some notable examples for hikers include:

- Bisse du Ro (Crans-Montana): Once one of the most dangerous to maintain, this bisse is now a secured but thrilling walk, with sections clinging dramatically to a vertical cliff.

- Grand Bisse de Vex (Nendaz): At 12 kilometers long, this is one of the region’s major bisses, passing through forests and meadows and still used to irrigate raspberry and strawberry fields.

- Bisse d’Ayent: Famous for its spectacular aqueduct-like crossings and its history, which stretches back to 1442.

A Living Monument

To walk along a bisse is to walk through history. It is a tangible connection to a past where human ingenuity, courage, and cooperation triumphed over a challenging geographical reality. These channels are not dusty relics in a museum; they are living, breathing parts of the Valaisan landscape, their waters still nourishing fields and their paths still welcoming wanderers. They are a powerful symbol of how humanity can adapt to and shape its environment, leaving a legacy of beauty and utility carved into the very mountains themselves.