What Are the Carolina Bays? A Geographic Snapshot

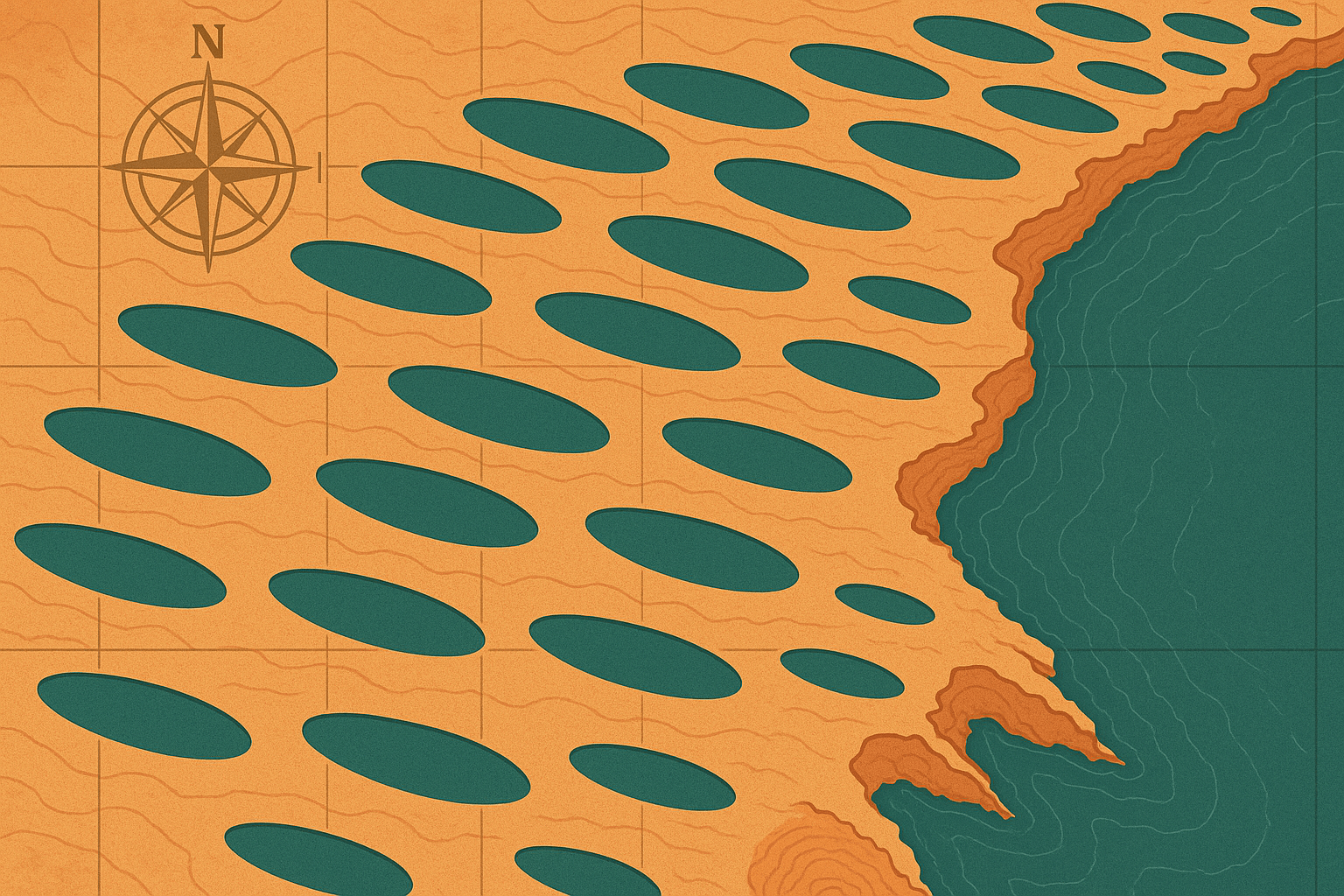

First identified from aerial photographs in the 1930s, the Carolina Bays are a distinct geographical phenomenon. While they exist in several states, their greatest concentration and most perfect forms are found in North and South Carolina, giving them their name. There are an estimated 500,000 of them.

Their key characteristics are strikingly consistent:

- Shape: A near-perfect elliptical or ovoid shape.

- Orientation: A uniform northwest-to-southeast alignment.

- Rims: Many possess a raised sandy rim, most prominently on their southeastern edge.

- Ecosystem: Because they are depressions that hold water, many bays have become unique wetland ecosystems known as “pocosins”—a Native American word for “swamp-on-a-hill.”

Some are immense. Lake Waccamaw in North Carolina and Lake Mattamuskeet, the state’s largest natural lake, are both believed to be giant Carolina Bays. For decades, scientists have stared at maps of these aligned ovals and asked the same question: What could have possibly formed them? The answers fall into two dramatically different camps: one involving a cataclysm from space, and the other, the patient work of earthly forces.

The Cataclysmic Hypothesis: Scars from a Cosmic Collision

The more spectacular of the two leading theories is the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis. Proponents of this idea argue that the Carolina Bays are the lingering wounds of a cosmic event that rocked the planet around 12,900 years ago.

The theory posits that a comet or asteroid fragmented and exploded in an airburst over North America, possibly above the Laurentide Ice Sheet that covered Canada and the northern U.S. at the time. This wasn’t a single crater-forming impact, but a barrage of devastation. The hypothesis suggests the event triggered a series of catastrophic effects:

- The Blast Wave: The super-heated airbursts would have sent a powerful shockwave across the continent, instantly melting or liquefying the sandy, water-logged soil of the Atlantic coastal plain.

- Secondary Impacts: Chunks of the disintegrating ice sheet, blasted into a sub-orbital trajectory by the primary impact, would have rained down across the Southeast. Traveling at thousands of miles per hour, these icy projectiles would have slammed into the liquefied ground, carving out the elliptical depressions.

This theory elegantly explains the Bays’ most puzzling features. The uniform alignment would be the result of all the ice boulders traveling in the same direction from a single point of origin. Their elliptical shape would be a natural outcome of a projectile striking the ground at a low angle. Furthermore, the timing aligns with the start of the Younger Dryas, a mysterious 1,300-year cold snap that abruptly reversed global warming, and coincides with the mass extinction of North American megafauna like mammoths, mastodons, and saber-toothed cats. Supporters point to a “black mat” layer in the soil from this period containing supposed impact markers like nanodiamonds and magnetic spherules as proof of a continent-wide catastrophe.

The Terrestrial Explanation: The Slow Hand of Wind and Water

While the impact theory is cinematic, most geologists today favor a more gradual, terrestrial explanation known as the Aeolian/Lacustrine Model. This theory argues that the Carolina Bays were not formed in a single, violent moment but were slowly sculpted over thousands of years by the simple, relentless action of wind and water.

This model suggests the Bays began as random ponds and depressions on the landscape during the end of the last Ice Age. At that time, the climate was different, and strong, consistent winds blew across the region, likely from the southwest or northwest. According to the theory:

- Strong, steady winds blowing over the shallow ponds created waves.

- These waves generated a circulating current within the water, much like stirring a cup of coffee.

- This gyroscopic motion eroded the shores, gradually shaping the ponds into an elliptical form, with the long axis oriented perpendicular to the prevailing wind direction.

- Sand and sediment stirred up by the waves were deposited on the downwind side of the ponds, forming the characteristic sandy rims seen on the northeast and southeast edges today.

Evidence for this process-based theory is compelling. Scientists have used a technique called Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) to date the sand grains in the bay rims. The results show that the rims were built up over long periods and that different bays formed at different times, contradicting the single-event impact hypothesis. Similar oriented lakes created by wind processes can be found today in places like the Alaskan tundra and coastal plains of South America, providing a modern analogue.

A Landscape of Debate and Ecological Wonder

The debate is far from settled. Impact proponents argue that the wind-and-water model fails to adequately explain the sheer number and mathematical perfection of the bays across such a vast area. Geologists favoring the terrestrial model point to the lack of definitive, undisputed impact evidence (like shocked quartz) within the bays and the powerful OSL dating that supports a gradual process.

Regardless of their origin, the Carolina Bays are a vital and fascinating part of the American landscape. From an ecological perspective, their unique wetland environments are biodiversity hotspots. The acidic, nutrient-poor soil of the pocosins is the only place on Earth where the carnivorous Venus flytrap grows naturally. They are also home to pitcher plants, orchids, and a variety of amphibians and reptiles.

From a human geography standpoint, the Bays have long shaped settlement and land use. For centuries, many were seen as impassable, swampy obstacles. In the 20th century, many were drained for agriculture, their rich peat soils proving highly fertile for farming. Today, a balance is sought between development and conservation, with many pristine bays protected in state parks and nature preserves, like South Carolina’s Woods Bay State Park.

Whether they are the faint scars of a celestial bombardment or the elegant product of wind and water, the Carolina Bays are a powerful reminder that our planet’s surface is a dynamic canvas. They are a silent, sprawling testament to immense forces, inviting us to look closer and wonder about the profound secrets the land still holds.