The Heart of the Matter: The Congolese Copperbelt

Our map begins in the southern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), specifically Lualaba and Haut-Katanga. This region is part of the Central African Copperbelt, a massive geological formation that slices through the DRC and Zambia. It’s one of the planet’s richest treasure chests, holding over 70% of the world’s known cobalt reserves, which are typically found alongside copper deposits.

The human geography here is as dramatic as the physical. The city of Kolwezi, the world’s cobalt capital, is a chaotic boomtown. A dusty red haze from mining operations perpetually hangs in the air. Here, two starkly different worlds of extraction coexist. On one side are the massive, industrial open-pit mines, often owned by multinational corporations, primarily Chinese. These are vast, terraced landscapes carved by giant machinery.

On the other side is the world of artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). An estimated 200,000 people, known as creuseurs (diggers), work in this informal sector. They descend into hand-dug, unstable tunnels, sometimes hundreds of feet deep, with no safety equipment, using only basic tools like shovels and hammers. They are searching for heterogenite, the dark, cobalt-rich rock. This is where the cobalt chain’s most severe human rights abuses are concentrated, including frequent tunnel collapses and the well-documented exploitation of child labor.

This cobalt rush has triggered immense internal migration, as people from impoverished rural areas flock to mining hubs like Kolwezi and the provincial capital, Lubumbashi. This rapid, unplanned urbanization strains already fragile infrastructure, creating sprawling informal settlements that lack clean water, sanitation, and electricity. It’s a textbook example of the “resource curse”—a geographical paradox where a land of immense natural wealth remains home to some of the world’s poorest people, its riches siphoned away by corruption and foreign interests.

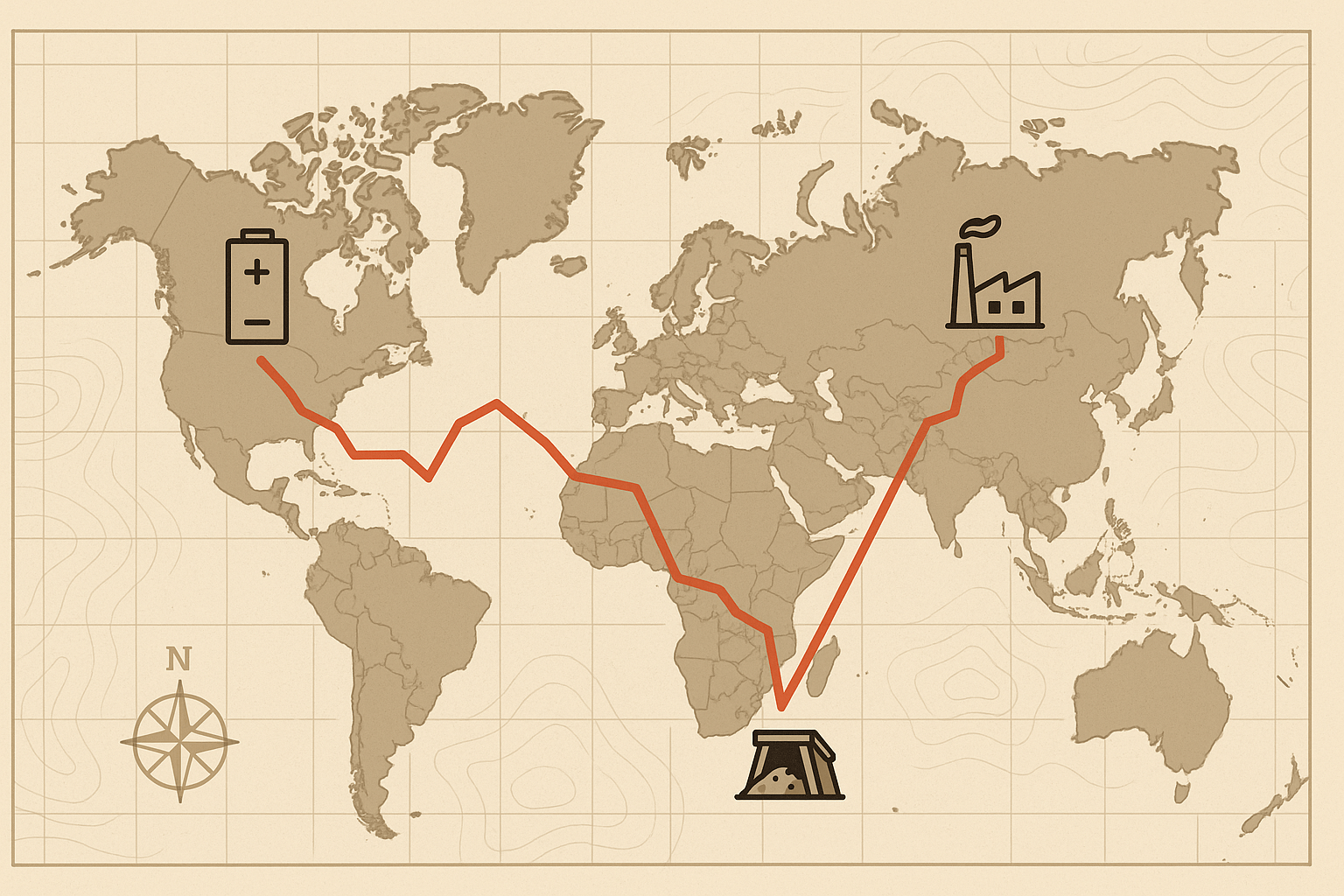

The Long Haul: From African Mines to Chinese Refineries

Once dug from the earth, the cobalt ore begins a long and complex journey. The rocks gathered by creuseurs are sold to local trading depots, or comptoirs. These depots are the first major chokepoint in the supply chain, and they are overwhelmingly dominated by Chinese middlemen who consolidate the ore before it enters the formal, global market.

From the landlocked Copperbelt, the cobalt must find its way to the sea. The geography of African infrastructure dictates its path. Convoys of trucks rumble for thousands of kilometers along precarious roads to major ports. Key routes include the southern corridor to Durban in South Africa, the eastern corridor to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, or the western corridor to Lobito in Angola. Each route is a testament to the logistical challenges of operating in Central Africa.

Once at the port, the sacks of raw ore and concentrate are loaded onto massive cargo ships. They cross the Indian Ocean, navigate the Strait of Malacca—one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes—and sail through the South China Sea. Their destination: China.

China’s Chokehold on Cobalt Processing

While the DRC is the source of cobalt, China is its crucible. Over 70% of the world’s cobalt is refined within Chinese borders. This dominance isn’t based on geology—China has negligible cobalt reserves. It’s a product of strategic industrial geography. Through decades of calculated state-backed investment, companies like Huayou Cobalt and China Molybdenum have not only bought up significant mining assets in the DRC but have also built a near-monopoly on the complex chemical process of refining raw ore into high-purity cobalt metal and salts.

The epicenters of this industry are located in coastal provinces like Zhejiang and Jiangsu. Here, in sprawling industrial parks, the African ore is transformed. These refining facilities represent a critical node of power in the global economy. By controlling this midstream stage, Beijing holds immense leverage over the entire battery and electric vehicle (EV) industry.

This strategy is deeply intertwined with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Chinese financing for roads, rail, and port infrastructure in Africa isn’t just about development; it’s about securing and streamlining the geographic pathways that feed raw materials to its industrial heartland.

From Cathodes to Consumers: The Final Assembly

In Chinese refineries, the purified cobalt becomes a key ingredient in “cathode precursors”, a fine powder that forms the positive electrode in a lithium-ion battery. This powder is then shipped to another set of factories—the battery mega-factories, or “gigafactories.”

The geography of this final stage is becoming more distributed. While Chinese firms like CATL and BYD are world leaders, battery production is a global enterprise. Cathode materials are shipped to factories in South Korea (LG Energy Solution), Japan (Panasonic), Europe (like Northvolt’s plant in Skellefteå, Sweden), and the United States (Tesla’s Gigafactories in Nevada and Texas).

In these high-tech facilities, the cobalt-laced cathode is combined with an anode, separator, and electrolyte, then packaged into the battery cells that power everything from an iPhone to a Ford Mustang Mach-E. Finally, these batteries are integrated into devices and vehicles, completing a global journey that spans three continents and links some of the poorest laborers on Earth to its most affluent consumers.

Navigating a More Ethical Cobalt Geography

The cobalt chain is a fragile line drawn across the globe, a 10,000-kilometer odyssey from a hand-dug Congolese tunnel to a gleaming EV showroom. Understanding its geography—from the physical constraints of the Copperbelt to the strategic chokepoints of Chinese industry—is crucial.

Change is slowly being mapped out. Efforts to improve traceability using blockchain, corporate due diligence laws, and formalization programs for artisanal miners aim to make the supply chain more transparent and ethical. Furthermore, intense research into cobalt-free battery chemistries, like Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP), promises a potential technological escape route from this fraught dependency. But for now, the screen you are reading this on remains inextricably linked to the red earth of the Congo and the complex, often brutal, map of power and peril that defines the cobalt chain.