A Land Forged by Tectonic Fury

To understand the Danakil’s extreme nature, we must look deep beneath the Earth’s crust. This region is a textbook example of a tectonic triple junction, a rare and volatile point where three of the planet’s tectonic plates meet and are actively pulling apart. Here, the African, Somali, and Arabian plates are diverging in a slow but relentless continental dance.

This immense stretching and pulling has created the Great Rift Valley, and the Danakil Depression is its northernmost extension. As the continental crust thins, the land subsides, sinking dramatically below sea level. This process also allows magma from the Earth’s mantle to push closer to the surface, fueling the region’s volcanic activity. The famous Erta Ale, one of the world’s few continuously active lava lakes, is a direct and dramatic consequence of this powerful geology. The Danakil isn’t just a low-lying desert; it’s a place where the planet is literally tearing itself apart, offering a raw glimpse into the forces that shape our world.

The Geography of Extremes

The Danakil Depression holds several formidable geographic records. It is one of the lowest places on the planet, with its most dramatic feature, the Dallol hydrothermal fields, sitting at approximately 125 meters (410 feet) below sea level. It is also, by measure of average year-round temperatures, the hottest inhabited place on Earth. Daily highs frequently soar above 45°C (113°F), and temperatures rarely dip below 34°C (94°F) even on the “coolest” days.

This incredible heat and low elevation are intrinsically linked. Millions of years ago, this basin was connected to the Red Sea. As tectonic shifts isolated the area, the inlet dried up, leaving behind immense salt deposits, some several kilometers thick. The low elevation creates a high-pressure environment that traps heat, while the lack of vegetation and cloud cover means the sun’s energy beats down relentlessly on the salt and dark volcanic rock, creating a natural convection oven.

Dallol: Earth’s Alien Canvas

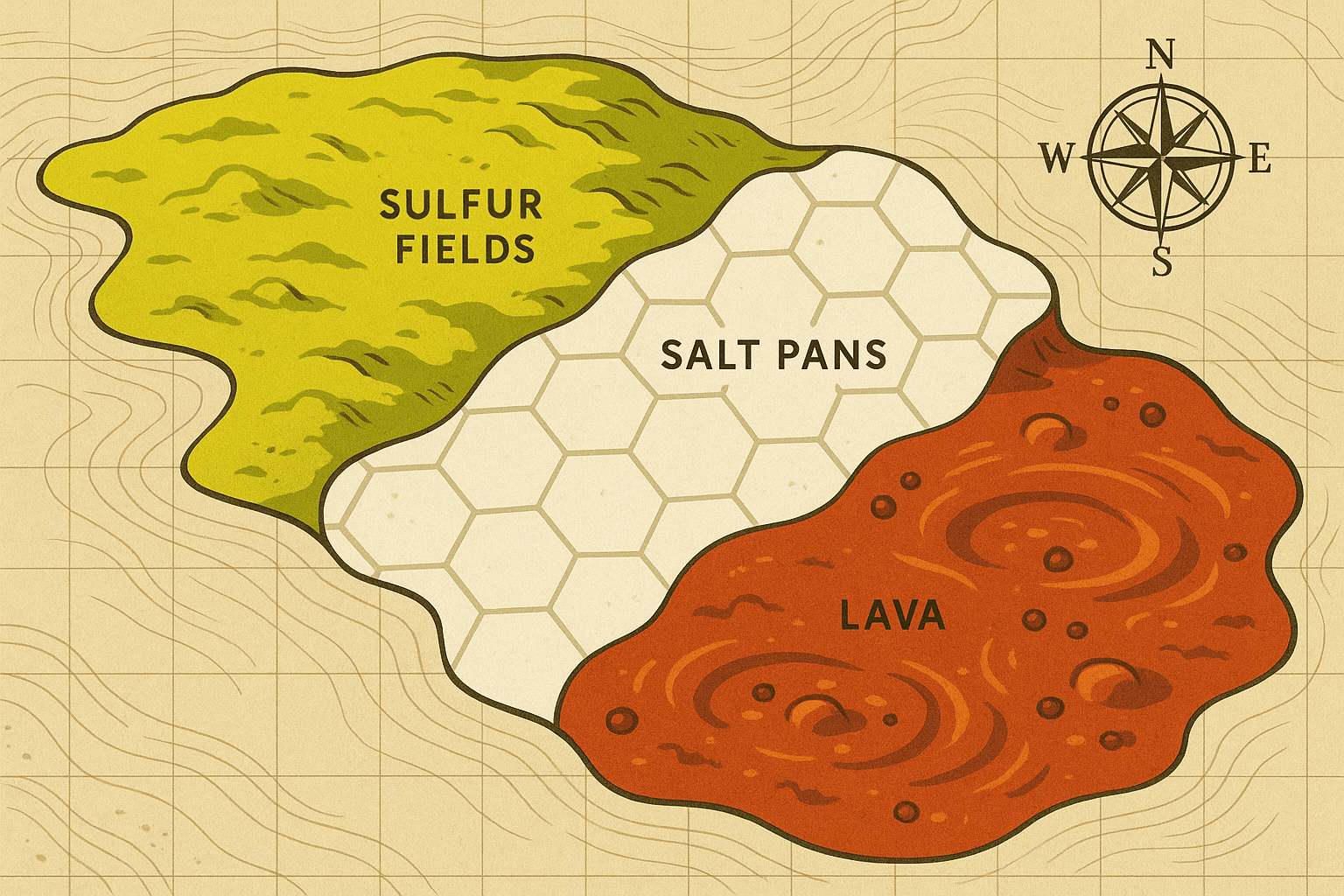

The crown jewel of the Danakil is Dallol, a geological wonderland that defies belief. It’s a landscape painted by geothermal activity. Here’s what creates its otherworldly palette:

- Vibrant Yellows and Oranges: These brilliant hues come from sulfur and iron salts precipitating out of hot brine.

- Acidic Greens: When hot, acidic water dissolves copper salts, it creates startlingly green pools. These are not for swimming—the liquid can have a pH level of less than 1, more acidic than battery acid.

- Earthy Reds and Browns: These colors are formed by the oxidation of iron minerals within the brine.

- Glistening Whites: The landscape is underpinned by vast deposits of salt, which crystallizes into intricate, mushroom-like formations and delicate crusts.

This entire spectacle is created when groundwater, heated by underlying magma, is forced to the surface. This water becomes a super-saturated, super-heated, and highly acidic brine rich in dissolved minerals. As it bubbles up and evaporates in the scorching heat, it leaves these mineral deposits behind, constantly building and reshaping the fragile, toxic landscape. Walking here requires an experienced guide, as the ground is often a thin, brittle crust hiding boiling-hot liquid just beneath.

The White Gold and the Camel Caravans

Beyond the technicolor springs lies another, more monolithic landscape: the salt flats of Lake Asale. Stretching to the horizon, this vast, blindingly white plain is what remains of the ancient evaporated sea. For centuries, this salt has been the economic lifeblood of the region, a commodity so valuable it was once used as currency and referred to as “white gold.”

This is where the physical geography of the Danakil intersects dramatically with its human geography. For generations, the local Afar people have endured the punishing conditions to mine this salt. Using rudimentary axes and wooden poles, the miners pry large, uniform slabs of salt—called amole—from the ground. These heavy blocks are then carefully shaped and loaded onto the backs of camels and donkeys.

What follows is one of the last great traditional trade routes on the planet. The Afar lead these camel caravans on a grueling, multi-day trek across the desert, transporting the salt to market towns like Mekele in the Ethiopian highlands. It is a testament to human endurance and adaptation, a tradition that has survived in one of the most inhospitable environments imaginable.

A Window to Life on Other Planets

The extreme conditions of the Danakil Depression have made it a focal point for astrobiologists. Scientists study the hardy microbes, known as extremophiles, that manage to survive and thrive in the boiling, acidic, and saline pools of Dallol. By understanding how life can exist in such a hostile place on Earth, researchers can better hypothesize about the potential for life to exist in similarly harsh environments on other planets and moons in our solar system.

A journey to the Danakil Depression is more than just an adventure; it’s a profound lesson in geology, chemistry, and human resilience. It is a place of stark contrasts: breathtakingly beautiful yet dangerously toxic, ancient yet constantly changing. It is a reminder that our planet still holds landscapes so wild and extreme they challenge our very definition of what it means to be alive.