The Hub-and-Spoke: A Geographical Masterstroke

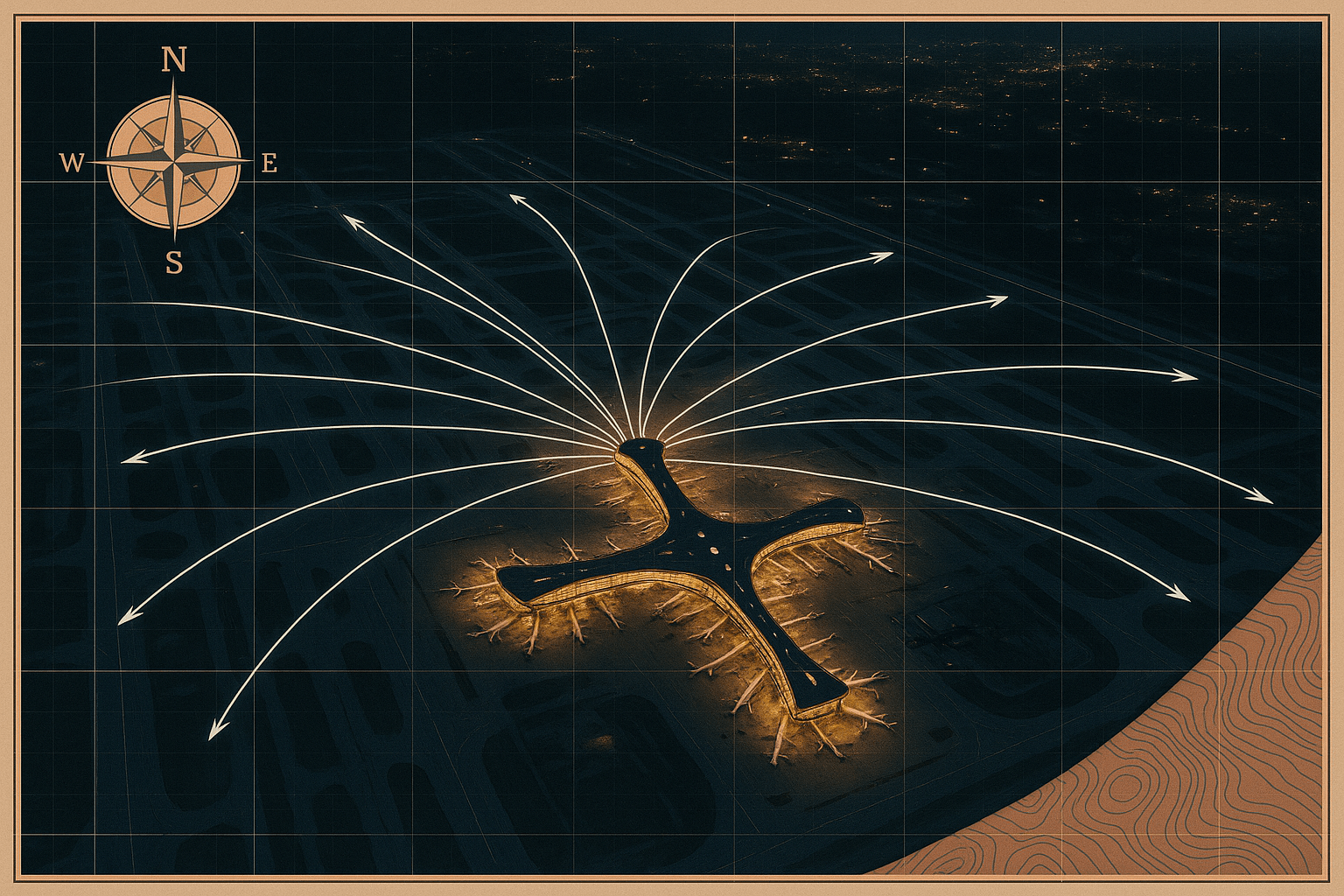

The dominant model for air travel today is the hub-and-spoke system. Imagine trying to connect ten small towns. A “point-to-point” system would require 45 separate flight routes. It’s inefficient and expensive. The hub-and-spoke model, however, establishes one central airport (the hub) and connects each of the ten towns (the spokes) to it. Now, you only need ten routes. Passengers from Town A fly to the hub and then transfer to a flight to Town B.

This model is pure geographical efficiency. Airlines can consolidate passengers onto larger, more economical aircraft for the trunk routes between hubs, while using smaller planes for the spokes. This concentrates resources, increases flight frequencies, and ultimately connects more places than would otherwise be possible. But the success of this entire system hinges on one critical question: where do you place the hub?

Winning the Geographical Lottery: The Power of Position

The perfect hub location is a winning ticket in the geographical lottery, a blend of physical and human geography that gives an airport an almost unfair advantage.

Physical Geography: The Planet’s Crossroads

The most crucial factor is absolute location. Consider Dubai International Airport (DXB). For centuries, this region was a peripheral desert landscape. But look at a globe, and its modern advantage becomes clear. Dubai is strategically positioned at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Approximately two-thirds of the world’s population lives within an eight-hour flight, and the remaining third is reachable within sixteen hours. This unparalleled centrality allowed Emirates airline, with the full backing of the government, to build a “super-connector” hub. A passenger flying from Sydney to London or from Johannesburg to Beijing finds Dubai a perfectly logical and convenient transfer point.

Now, contrast this with Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL), consistently one of the world’s busiest. Its power isn’t global centrality, but continental centrality. Atlanta sits within a two-hour flight of over 80% of the United States’ population. For Delta Air Lines, this makes it the ultimate domestic hub, a giant sorting facility for passengers crisscrossing the nation. Its location is the primary reason it funnels more passengers than almost any other airport on Earth.

Beyond location, physical geography also includes climate and topography. Dubai’s clear skies and stable weather mean fewer delays. Both Dubai and Atlanta are built on relatively flat, expansive terrain, allowing for the multiple, parallel runways necessary for high-volume operations—a luxury not afforded to airports hemmed in by mountains or coastlines.

Human Geography: The Engine of Growth

A prime location is useless without the right human factors. A successful hub requires:

- Political & Economic Will: The government of Dubai didn’t just get lucky; they engineered their success. They pursued “Open Skies” agreements, invested billions in state-of-the-art infrastructure, and built their national airline, Emirates, into a global behemoth. The airport became a cornerstone of their economic strategy to move beyond oil. This concept, known as an “aerotropolis”, is a city deliberately built around its airport.

- A Strong Local Market: While transfer passengers are key, a hub needs a strong Origin and Destination (O&D) market. People must want to start or end their journeys there. Atlanta is the economic and cultural capital of the American Southeast, a massive business and population center. Dubai has transformed itself into a global destination for tourism, finance, and trade. This base load of O&D passengers provides a stable revenue stream and justifies routes that might not survive on transfer traffic alone.

Designing the Space: The Airport as a Micro-Geography

Once the location is chosen, the airport itself must be designed as an efficient micro-geography. The layout of terminals, concourses, and runways is a direct response to the hub’s primary function.

The Atlanta Model (The Midfield Concourse): Atlanta’s design is a symphony of parallel lines. It features a main terminal connected to a series of long, parallel midfield concourses (T, A, B, C, D, E, F) by an incredibly efficient underground train. This layout is genius for a domestic hub focused on transfers. It allows for a maximum number of aircraft to park at gates simultaneously and minimizes taxi times, as planes don’t have to cross active runways to get to the terminal. A passenger can deplane at one end of the airport, hop on the train, and be at their connecting gate at the other end in minutes. It’s a spatial solution to a logistical nightmare.

The Dubai Model (The Mega-Terminal): Dubai’s Terminal 3, one of the largest buildings in the world by floor space, was purpose-built for Emirates and the Airbus A380. Its design reflects its role as a global super-connector. The layout is vast and linear, designed to process enormous waves of international transfer passengers with maximum efficiency. The focus is on smooth, seamless connections—from security to shopping to the gate—for travelers who may only spend a couple of hours in the country. The scale itself is a geographical statement, built to accommodate the flows of a globalized world.

The Airport as a Geographical Phenomenon

A perfect airport hub is far more than concrete and glass. It is a geographical phenomenon, born from a confluence of global position, continental advantage, political ambition, and brilliant spatial design. From the grand scale of its position on the globe to the micro-geography of its terminal layout, every element is a calculated decision to conquer distance and time.

The success of hubs like Dubai and Atlanta proves that in our interconnected world, geography is not just a passive backdrop—it is the very blueprint for connection. They are not merely places of transit, but powerful engines that shape economic regions, dictate global flows, and redefine our mental maps of the world.