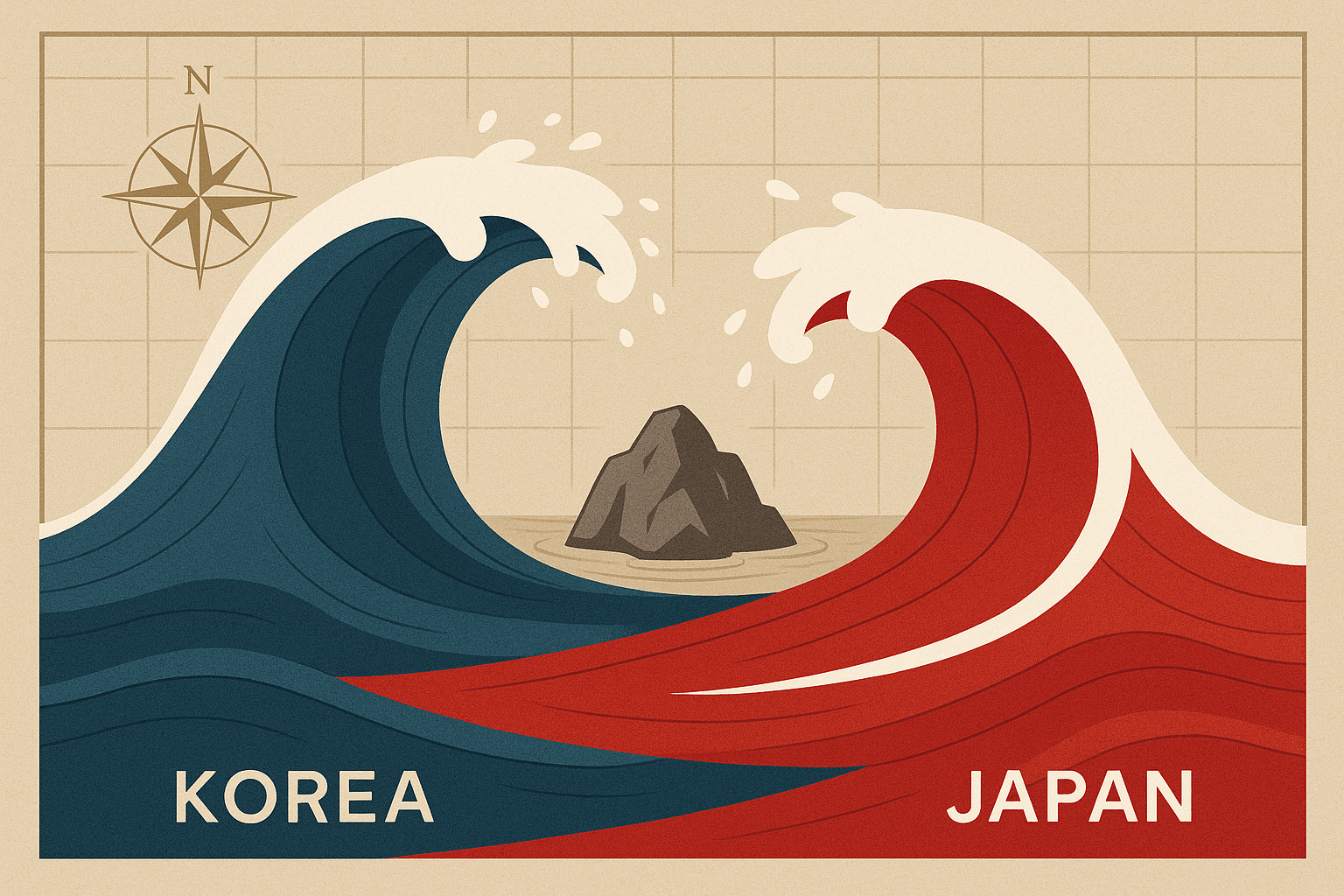

In the vast expanse of water separating the Korean peninsula from the Japanese archipelago, there lies a tiny cluster of islets. To the world, they are often known by their 19th-century European name, the Liancourt Rocks. But to the two nations who claim them, they are a crucible of national pride and geopolitical tension. South Korea calls them Dokdo (독도, “Solitary Island”). Japan calls them Takeshima (竹島, “Bamboo Island”). These seemingly insignificant rocks are the epicenter of one of the most intractable territorial disputes in modern geography, a conflict fueled by history, economics, and powerful nationalist sentiment.

A Speck on the Map: The Physical Geography

To understand the dispute, one must first understand the place itself. Dokdo/Takeshima consists of two main volcanic islets—the larger West Islet (Seodo/Nishi-jima) and the East Islet (Dongdo/Oki-no-shima)—surrounded by dozens of smaller barren rocks. Their total surface area is a mere 0.187 square kilometers (about 46 acres), roughly the size of a small city park.

Geographically, they are located in the body of water that South Korea calls the East Sea and Japan, along with most of the world, calls the Sea of Japan. This naming controversy is, itself, a microcosm of the larger dispute. The islets are situated approximately:

- 87 kilometers southeast of South Korea’s Ulleungdo Island.

- 157 kilometers northwest of Japan’s Oki Islands.

This proximity is a key geographical fact in both countries’ claims. Geologically, the islets are the eroded peaks of an ancient underwater volcano, part of the same volcanic ridge as the much larger Ulleungdo. The environment is harsh; the rocks are windswept, soil is scarce, and there is very little natural fresh water, making sustained human settlement nearly impossible without significant external support.

The Human Geography: A Tale of Two Names and One Presence

While historically uninhabited, the islets today have a distinct human footprint, which forms a crucial part of South Korea’s claim of de facto control. The East Islet hosts a small but permanent South Korean presence, including:

- A detachment of the South Korean Coast Guard.

- A lighthouse and a helicopter pad.

- Symbolically, a registered civilian couple who officially reside there.

This presence transforms the islets from abstract territory into a defended and administered part of the South Korean state. For Seoul, the message is clear: Dokdo is not just claimed, it is occupied and governed. Japan, conversely, views this as an illegal occupation of its sovereign territory and regularly lodges diplomatic protests against any South Korean activity on or around the islets, from military drills to the construction of new facilities.

The human geography extends beyond the rocks themselves. In both South Korea and Japan, the islands are deeply embedded in the cultural and educational landscape. South Korean children sing “Dokdo is Our Land”, and the islets feature prominently in school curricula. In Japan, Shimane Prefecture, which officially administers Takeshima, established “Takeshima Day” on February 22nd to commemorate its 1905 incorporation of the islands, an event that provokes outrage in Seoul each year.

Reading the Historical Map: Contested Claims

The historical arguments are a labyrinth of ancient maps, royal decrees, and post-war treaties, with each side presenting evidence to bolster its claim.

South Korea’s Historical Claim:

South Korea asserts that its sovereignty dates back to the 6th century. It cites ancient texts, like the Samguk Sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms), which record the absorption of the state of Usan-guk in 512 A.D. Seoul maintains that Usan-guk included both Ulleungdo and Dokdo. A more concrete piece of evidence for Korea is the Imperial Ordinance No. 41 from 1900, which placed Ulleungdo and its appended islands, including a “Seokdo” (石島, Stone Island), under the jurisdiction of Ulleung County. South Korea argues that “Seokdo” is an ancient name for Dokdo.

Japan’s Historical Claim:

Japan contests these ancient claims, arguing the historical references are ambiguous. Instead, Japan points to evidence of its use of the islands for fishing and sea lion hunting from at least the 17th century. The cornerstone of Japan’s modern claim is the Shimane Prefecture Notification No. 40 of February 22, 1905. This act officially incorporated the islets, then internationally known as the Liancourt Rocks, into Japanese territory under the name “Takeshima.” For Japan, this was an act of incorporating terra nullius (unclaimed land). For South Korea, this was a cynical first step in Japan’s colonization of Korea, which was formally annexed five years later in 1910.

The pivotal moment in the modern dispute came after World War II. The 1951 Treaty of San Francisco, which formally ended the war between Japan and the Allied Powers, stipulated that Japan must renounce all rights to Korea. However, the treaty failed to explicitly mention Dokdo/Takeshima, creating a legal vacuum that both sides have exploited ever since.

More Than Just Rocks: Strategic and Economic Geography

If the islets were merely barren rocks, the dispute might have faded. But their location grants them immense strategic and economic value, turning them from a historical quarrel into a modern geopolitical flashpoint.

Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a country can claim an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles (370 km) from its coastline. Even tiny islets can generate a vast EEZ. Control over Dokdo/Takeshima grants sovereign rights over the surrounding waters, which are some of the richest fishing grounds in the region, particularly for squid and saury.

Beyond fish, there is the tantalizing potential for undersea resources. Geological surveys have indicated the possible presence of vast deposits of methane hydrates (a form of natural gas) in the seabed around the islets. While currently not commercially viable to extract, their potential future value adds a significant economic incentive to the sovereignty claim. Furthermore, the islets hold military value as a potential base for radar installations to monitor air and sea traffic in a strategically vital shipping lane.

A Symbol of Sovereignty

Ultimately, the Dokdo/Takeshima dispute transcends legal arguments and resource competition. For South Korea, the islets are a powerful symbol of its sovereignty and its recovery from the brutal period of Japanese colonial rule. Any perceived concession on Dokdo is seen as a betrayal of national identity and a capitulation to a former colonizer. For Japan, the issue is a matter of upholding international law and defending its territorial integrity against what it views as an illegal post-war seizure.

These two tiny islets in the Sea of Japan/East Sea are a stark reminder that in geography, size is not always what matters most. It is the meaning, history, and potential that humans ascribe to a place that gives it power. As long as Dokdo/Takeshima represents the unresolved traumas of the past and the strategic calculations of the future, they will remain a potent symbol of division between two of Asia’s most important nations.