Now, take that challenge and square it. Imagine being a country surrounded entirely by other landlocked countries. This is the unique and extreme geographical predicament known as being “double landlocked.” To get a single shipping container from your country to a port, you must cross not one, but at least two international borders. In the entire world, only two nations hold this remarkable distinction: Liechtenstein in Europe and Uzbekistan in Central Asia.

While they share this rare geographical status, their stories of navigating this challenge could not be more different, offering a fascinating lesson in how geography, scale, and strategy intersect.

Liechtenstein: The Alpine Anomaly

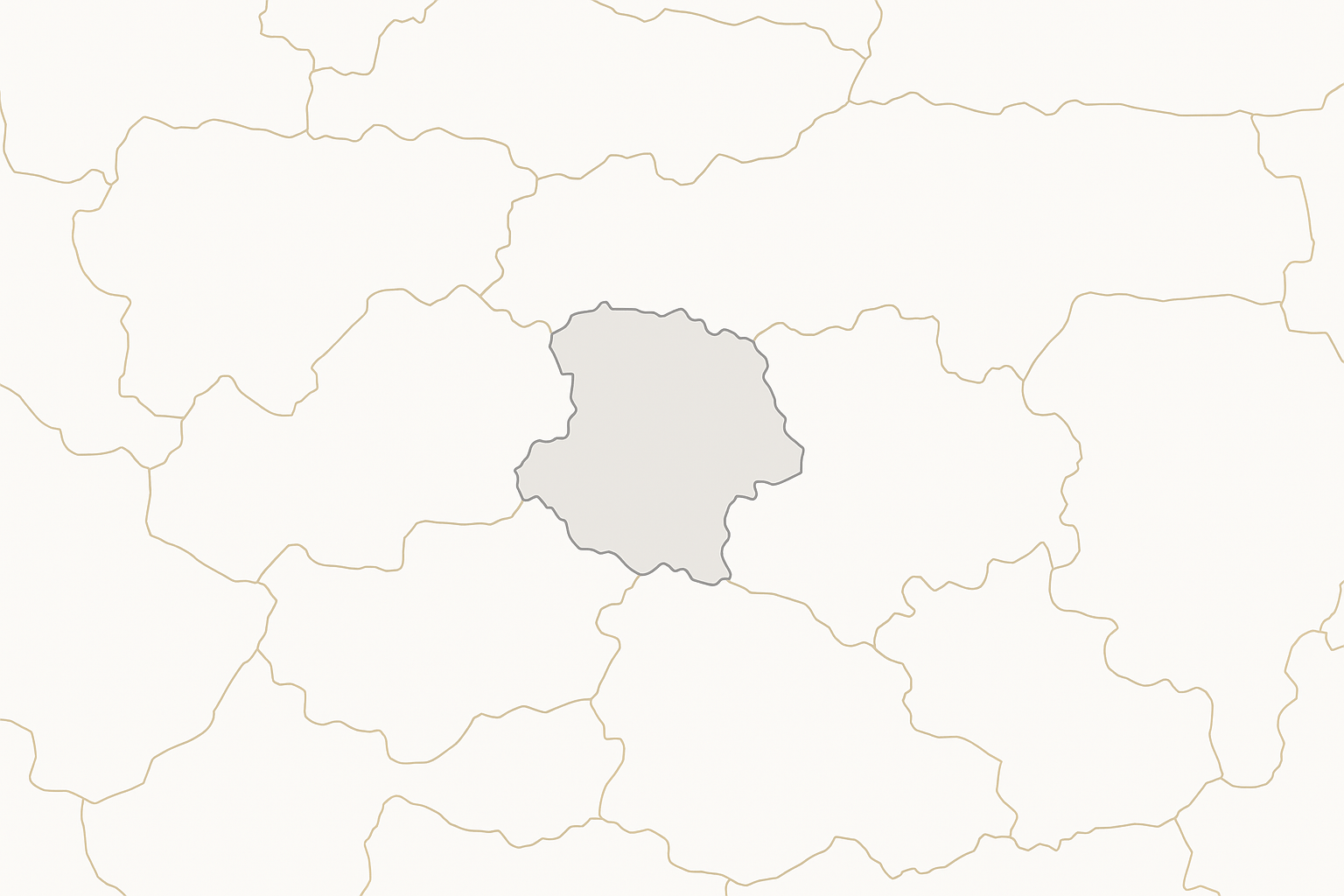

Tucked neatly between Austria and Switzerland, the Principality of Liechtenstein is a tiny, mountainous nation covering just 160 square kilometers (62 sq miles). It’s a place of fairytale castles, pristine alpine meadows, and a population smaller than many city neighborhoods. To its east lies landlocked Austria, and to its west, landlocked Switzerland. To reach the nearest major seaport—Genoa, Italy—a truck leaving Liechtenstein’s capital, Vaduz, must first cross all of Switzerland.

How a Microstate Overcomes the Odds

So how does a double landlocked nation not only survive but become one of the wealthiest countries in the world per capita? Liechtenstein’s success is a masterclass in adaptation and specialization.

- Economic Specialization: Liechtenstein doesn’t deal in bulky, low-value commodities. Instead, its economy is built on high-value, low-volume goods and services. It is a global leader in producing dental products like false teeth and high-tech precision instruments. More famously, it is a major financial hub, specializing in banking and wealth management. These “products” can be moved across borders digitally or in a briefcase, making sea access irrelevant.

- Deep Integration: Geography may have isolated Liechtenstein, but politics and economics have connected it. The country is in a full customs and monetary union with Switzerland. It uses the Swiss Franc, and for most practical purposes, the border between the two is seamless. By aligning itself with the stable, prosperous, and well-connected Swiss economy, Liechtenstein effectively piggybacks on its neighbor’s success.

- Leveraging European Connectivity: As part of the Schengen Area, goods and people can move freely between Liechtenstein, Austria, Switzerland, and beyond. Its location in the heart of Europe, serviced by a dense network of high-quality roads and railways, means that while the sea is far, major European markets are just a short drive away.

For Liechtenstein, being double landlocked is more of a geographical fun fact than a crippling disadvantage. Its small size, smart economic strategy, and deep integration have rendered the challenge almost moot.

Uzbekistan: The Central Asian Crossroads

Half a world away, the story of the second double landlocked nation is one of a vastly different scale and complexity. Uzbekistan is a sprawling nation of over 35 million people, a land of ancient Silk Road cities like Samarkand and Bukhara, vast deserts like the Kyzylkum, and fertile river valleys. Its challenge is defined by its five neighbors, all of whom are also landlocked: Kazakhstan to the north, Turkmenistan and Afghanistan to the south, and Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to the east.

The Tyranny of Distance

For Uzbekistan, being double landlocked is a formidable economic and geopolitical reality that shapes its national strategy. Unlike Liechtenstein, Uzbekistan’s economy has historically relied on the export of bulk commodities.

- High Transport Costs: Its primary exports include cotton, natural gas, gold, and other minerals. Moving these heavy, bulky goods requires crossing multiple borders, each with its own customs procedures, transit fees, and potential for delays. This “tyranny of distance” adds a significant cost to every ton of cotton or cubic meter of gas sold on the global market, making its products less competitive.

- Geopolitical Dependence: Uzbekistan’s access to the world is entirely dependent on the political stability and goodwill of its neighbors. A diplomatic dispute with Turkmenistan could threaten its route to Iranian ports. Its most vital trade corridor runs north through Kazakhstan to connect with Russia’s rail network, giving both countries immense leverage. This was especially evident in the Soviet era, when all infrastructure was designed to point toward Moscow, not toward the nearest sea.

- The Aral Sea: A Lost Coastline: In a tragic irony, Uzbekistan once had access to a massive body of water—the Aral Sea. Once the world’s fourth-largest lake, Soviet-era irrigation projects diverted the rivers that fed it, causing it to shrink to a fraction of its former size. This man-made environmental catastrophe not only devastated the local fishing industry but also eliminated what was, in effect, a massive inland port.

Forging New Paths to the Sea

Despite these immense challenges, Uzbekistan is actively working to untangle its geographical knot. The government is pursuing an ambitious foreign policy aimed at turning its location from a disadvantage into an advantage as a central crossroads.

A key part of this strategy is embracing China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). New China-backed rail lines are being built to create efficient land-bridges across Central Asia, connecting Uzbekistan to ports in China, Pakistan (Gwadar), and Iran (Chabahar). Furthermore, Uzbekistan is spearheading regional cooperation, improving transport links and trade agreements with its Central Asian neighbors to create seamless corridors, such as the Lapis Lazuli Corridor that connects the region to Europe via the Caucasus and Turkey.

A Tale of Scale and Strategy

Liechtenstein and Uzbekistan are the only two members of the world’s most exclusive geographical club, yet their experiences reveal everything about context.

Liechtenstein’s story is one of niche adaptation. By becoming a specialist in high-value services and integrating deeply with its neighbors, it turned its small size and landlocked status into an afterthought. Uzbekistan’s story is one of grand strategy. As a large, populous nation rich in resources, it cannot ignore its geography; it must actively reshape its connections to the world through massive infrastructure projects and complex diplomacy.

Together, they show us that while geography presents a set of undeniable facts, it is not destiny. With the right strategy, whether it’s specializing in finance or building a new Silk Road, even a nation twice-removed from the sea can find its path to the wider world.