These ancient sunken lanes are more than just footpaths; they are deep trenches carved into the earth, living documents of geography and history written over millennia. To walk a Holloway is to step back in time, treading the same ground as medieval drovers, Roman soldiers, and perhaps even prehistoric hunter-gatherers.

What is a Holloway? The Geography of a Sunken Lane

The name itself tells the story. “Holloway” derives from the Old English “holh weg”, which simply means “hollow way.” These routes are geographical phenomena born from a slow, persistent collaboration between humans and nature. The process of their creation is a perfect lesson in small-scale physical geography.

It begins with a simple track across soft, easily eroded ground. Southern England, particularly the counties of Dorset, Somerset, Sussex, and Hampshire, is rich in the perfect geological canvases for Holloways: soft sandstone, greensand, and chalk. The process unfolds over centuries:

- Human Traffic: Countless generations of people walking, herding livestock, and driving carts with iron-rimmed wheels begin to compact and wear down the surface of the track. The constant friction scrapes away particles of soil and rock.

- Animal Traffic: The hooves of thousands of cattle and sheep, being driven to market along these “drovers’ roads”, churned the soil, breaking it up and making it vulnerable.

- Water Erosion: This is the most powerful sculptor. As the path sinks even slightly, it becomes a natural channel for rainwater. Water, following the path of least resistance, rushes down the lane, carrying away the loosened soil and sediment. Over centuries, this process, known as fluvial erosion, carves the track deeper and deeper into the bedrock.

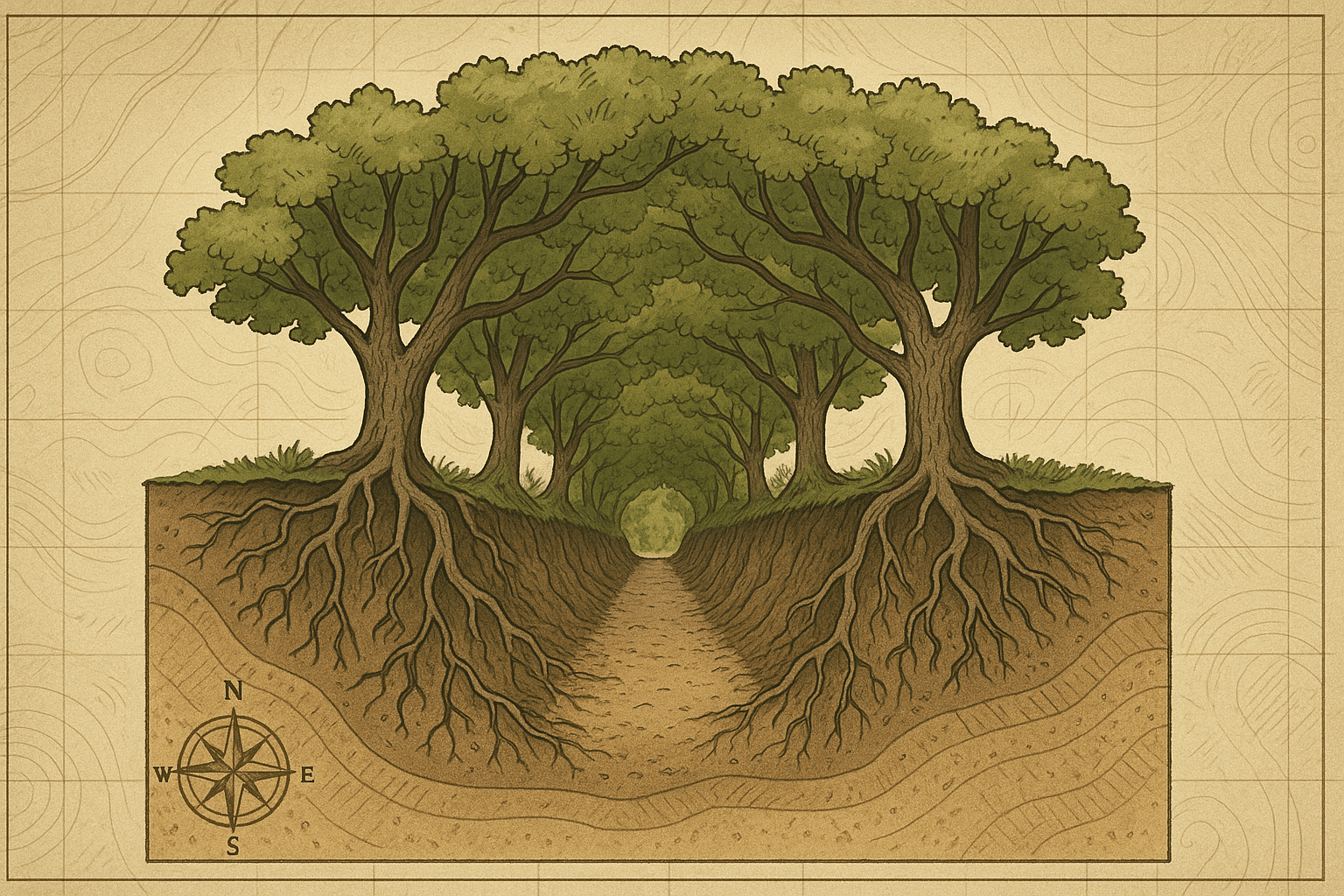

The result is a route that can be shockingly deep, sometimes sinking 5 or 6 meters (15-20 feet) below the level of the surrounding fields. The banks on either side are often near-vertical, a cross-section of the local geology held together by a dense web of tree roots.

A Walk Through Time: The Human Story

Every Holloway is a historical archive, its depth a measure of its age and use. They were the arteries of an older England, connecting villages, farms, and market towns long before tarmac and motorways. Their enclosed, hidden nature made them ideal for more than just everyday travel.

Many served as vital drovers’ roads. The high, steep banks acted as natural fences, creating a perfect funnel to guide herds of cattle or sheep without them straying into adjacent farmland. Walking one today, you can almost hear the faint echoes of hooves and the calls of the drovers.

Their secretive character also made them perfect smugglers’ routes. In coastal counties like Dorset and Sussex, contraband like brandy and tobacco, landed on remote beaches under the cover of darkness, would be spirited inland through this hidden network of sunken lanes, safe from the eyes of the excise men.

This deep connection to the past has not gone unnoticed by writers and artists. The nature writer Robert Macfarlane, in his seminal book The Old Ways, beautifully chronicles his journeys through these sunken paths, describing them as “routes that have been etched into the land by the traffic of feet and hooves and the run-off of water; they are the sunken, shadowed lanes of the English countryside.” They are a recurring, atmospheric feature in Thomas Hardy’s “Wessex” novels, landscapes imbued with memory and fate.

The Living Tunnel: A Unique Micro-Ecology

A Holloway is not just a geological and historical feature; it is a thriving, self-contained ecosystem. The deep cutting creates a unique microclimate—sheltered, shaded, and damp—that is distinct from the open, windswept fields above. This enclosed world fosters a specific and beautiful array of flora and fauna.

The steep banks are a vertical garden. The exposed, sandy soil is perfect for the roots of trees like oak, ash, and hazel to grip, their branches often reaching across the path to form a complete, cathedral-like canopy. This “living tunnel” creates a deep shade on the lane floor, where only certain plants can thrive.

In spring, the banks can be carpeted with shade-loving wildflowers like primroses, wood anemones, red campion, and fragrant wild garlic. Ferns are a quintessential Holloway plant, with species like the Hart’s-tongue fern unfurling its glossy, strap-like fronds in the damp air. The entire structure is stitched together by mosses and liverworts, which thrive in the cool, moist conditions.

This rich plant life provides a vital habitat for wildlife. The gnarled root systems and earthy banks offer perfect homes for badgers, foxes, weasels, and small rodents. The leafy canopy is alive with birdsong, providing a sheltered corridor for species like wrens, robins, and blackbirds to move safely across the landscape.

Where to Find England’s Holloways

While found in several parts of England, the most dramatic and famous Holloways are concentrated in the south. If you want to experience one for yourself, these are the regions to explore:

- Dorset: Arguably the capital of Holloway country. The area around Bridport and Beaminster is crisscrossed with spectacular examples. The most famous is perhaps Shute’s Lane, often called “Hell Lane”, a deeply cut, muddy, and atmospheric track that feels truly ancient.

- The Weald (Sussex & Kent): The High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty has a dense network of lanes, known locally as “gills”, that cut through its sandstone ridges.

- Somerset & Wiltshire: The soft limestone and chalk downs of these counties also feature numerous sunken lanes, often connecting ancient hillforts and settlements.

Many are now designated as public footpaths or bridleways, easily found on an Ordnance Survey map (look for the symbols for a “Byway Open to All Traffic” or “Restricted Byway”, often sinking between the contour lines).

Preserving a Living Heritage

Today, these remarkable features face threats from road widening, infilling for agricultural access, and general neglect. Yet, their importance is greater than ever. Holloways are not just paths; they are ecological corridors, historical records, and geological wonders. They are places that slow you down, forcing you to connect with the landscape and the deep history beneath your feet. To walk a Holloway is to feel the press of time and to understand that the simplest path can often hold the most profound stories.