To understand the complexity of this region is to understand one of the most challenging geopolitical legacies of the 20th century. It’s a story written in its very landscape, from the rivers that give it life to the borders that threaten to tear it apart.

A Jewel in a Mountainous Crown: The Physical Geography

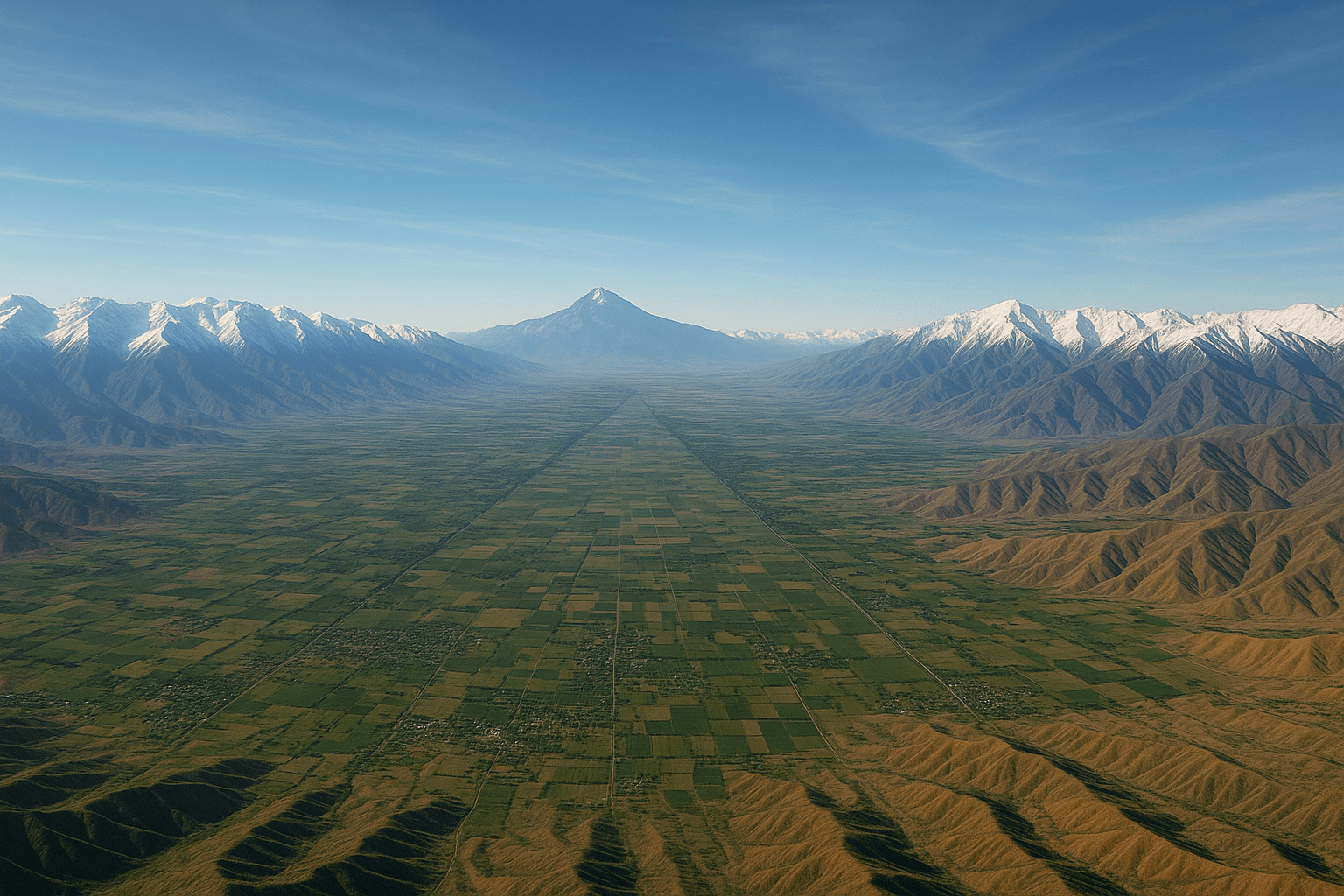

The Fergana Valley is a massive, triangular depression, covering some 22,000 square kilometers, cradled by the formidable Tien Shan mountains to the north and the Gissar-Alai range to the south. This unique topography is the source of both its wealth and its woes. For millennia, rivers like the Syr Darya and its headwaters, the Naryn and Kara Darya, have flowed down from the mountains, depositing rich alluvial soil across the valley floor. This has created an agricultural paradise in an otherwise arid and rugged part of the world.

The valley is famous for its cotton, but it also produces a bounty of fruits, vegetables, and silk. This fertility has supported a large population for centuries, making it the demographic core of Central Asia. The contrast is stark: a flat, green, and densely inhabited valley floor giving way abruptly to the sparsely populated, mountainous terrain of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. This simple geographical fact—that the life-giving water comes from the mountains and nourishes the plains—is central to the valley’s modern conflicts.

The Soviet Scissorhands: Forging the Borders

Before the 1920s, the concept of rigid, national borders was foreign to the people of the Fergana Valley. Identities were more fluid, centered on one’s town, clan, or faith. But with the rise of the Soviet Union came the policy of “national delimitation.” Soviet cartographers, driven by Joseph Stalin’s “divide and rule” strategy, set out to carve Central Asia into distinct Soviet Socialist Republics (SSRs).

Their goal was not to create logical, ethnically homogenous states. Instead, the borders were drawn to break up traditional power structures and ensure that each republic was dependent on the others, and ultimately on Moscow. The lines often followed bizarre logic, zigzagging to encompass a key railway, a vital irrigation canal, or a patch of cotton-growing land for a specific republic, while completely ignoring the ethnic makeup of the villages on either side.

The result was a masterpiece of geopolitical chaos. The most fertile and populous parts of the valley, historically dominated by Uzbek and Tajik speakers, were largely incorporated into the Uzbek SSR. The mountainous peripheries, home to nomadic and semi-nomadic Kyrgyz, became the Kyrgyz SSR. The valley’s western entrance, centered on the ancient city of Khujand, went to the Tajik SSR. The seeds of future conflict were sown deep into the administrative map.

Islands on Dry Land: The Enclave and Exclave Puzzle

The most bewildering legacy of this border-drawing frenzy is the proliferation of enclaves and exclaves. An enclave is a territory completely surrounded by the territory of another state. From the perspective of the home country, it’s an exclave—a piece of itself that is physically detached.

The Fergana Valley is littered with them, creating logistical nightmares and constant friction. Some of the most significant examples include:

- Sokh (Uzbekistan): A large exclave inside Kyrgyzstan, populated almost entirely by ethnic Tajiks. Its residents must cross Kyrgyz territory to reach mainland Uzbekistan, a journey fraught with checkpoints and potential delays.

- Vorukh (Tajikistan): A critical Tajik exclave located inside Kyrgyzstan. Access to Vorukh via a single road that passes through Kyrgyz territory is one of the most frequent and violent flashpoints in the entire region.

- Shohimardon (Uzbekistan): Another Uzbek exclave in Kyrgyzstan, a popular historical and pilgrimage site that is difficult for Uzbek citizens to access.

- Barak (Kyrgyzstan): A tiny Kyrgyz exclave, home to just a few hundred people, completely surrounded by Uzbekistan. Its residents have been left profoundly isolated.

For the people living in these territories, daily life is a struggle. A simple trip to a market, a hospital, or a relative’s house can involve crossing an international border multiple times. These “islands” are constant reminders of division and are highly vulnerable to blockades and disputes.

A Human Mosaic, A Cauldron of Tension

The Fergana Valley is not just a patchwork of borders, but a mosaic of people. Uzbeks form the majority on the valley floor, while Tajiks and Kyrgyz are significant minorities, often living in intermingled communities. For decades, Soviet authority suppressed any overt nationalism. But with the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the three republics gained independence, and the arbitrary borders suddenly became hard international frontiers.

Ethnic identity became more pronounced, and competition over scarce resources—land and water—intensified along these newly salient ethnic and national lines. Pastures that had been shared for generations were now claimed by one nation, angering communities on the other side. Disputes over unmarked sections of the border (of which there are still hundreds of kilometers) can erupt from something as simple as a farmer building a fence or a cow wandering across an imaginary line.

The Lifeblood of Conflict: Water and Land

Nowhere is the tension more palpable than in the struggle over water. The great rivers that irrigate Uzbekistan’s vast cotton fields originate upstream in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. During the Soviet era, a central system managed resource sharing: the downstream republics got water for agriculture, while the upstream republics received gas, coal, and electricity in return.

This system has completely broken down. Today, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, poor in fossil fuels, want to use their water resources to generate hydroelectricity by building dams. For downstream Uzbekistan, this is an existential threat. Dams would allow the upstream countries to control the flow, potentially holding back water during the crucial summer growing season to fill their reservoirs for winter power generation. This fundamental conflict—hydropower versus irrigation—pits the survival of one nation’s economy against another’s.

Can the Knot Be Untangled?

The Fergana Valley Knot is a complex tangle of history, geography, and human need. It is a stark illustration of how lines drawn on a map a century ago continue to shape lives, fuel conflict, and challenge the stability of an entire region.

Untangling it is a monumental task. In recent years, there have been glimmers of hope. Uzbekistan, under new leadership, has pursued a more cooperative “good neighbor” policy, leading to the reopening of many border crossings and progress on delimiting contested sections. However, core issues like the status of the exclaves and the sharing of water remain deeply contentious.

The path forward requires immense political will, compromise, and a shift in mindset from zero-sum competition to shared regional prosperity. The people of the Fergana Valley, bound together by a shared geography and a common history, must find a way to manage their shared future, or risk being forever trapped by the divisions of the past.