These internal divides, often far more significant than the differences between neighboring countries, are creating seismic shifts. They are quiet, slow-moving tectonic plates of demography that are reshaping the political landscapes, economic futures, and cultural identities of nations from the inside out.

The Great Divide: Urban Ambition vs. Rural Tradition

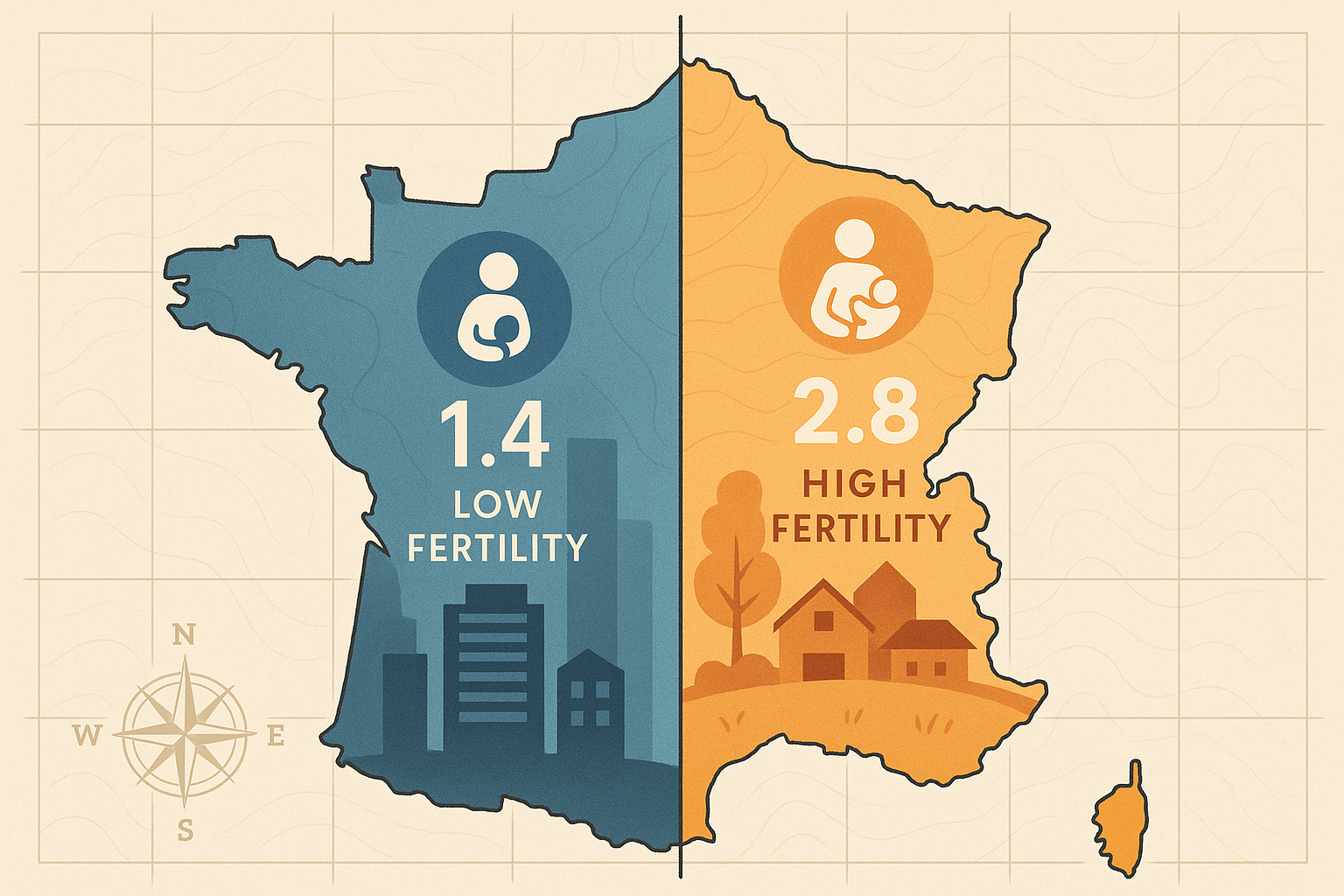

The most universal fertility fault line is the one that separates the city from the countryside. This is a story of human geography as old as civilization, but it has reached a demographic extreme in the 21st century.

In the world’s sprawling megacities—from Tokyo to London to New York—fertility rates are often astonishingly low. The reasons are a familiar cocktail of modern urban life:

- High Cost of Living: Raising children in a major city is astronomically expensive.

- Career Opportunities: Particularly for women, urban centers offer educational and professional paths that often compete with or delay childbearing.

- Cultural Norms: Urban environments tend to foster individualism and secularism, de-emphasizing the traditional imperative for large families.

A stark example is South Korea. While the national fertility rate is the world’s lowest at around 0.7, the rate in its capital, Seoul, is even lower, plummeting to a staggering 0.59. Meanwhile, rural provinces, while still low, have comparatively higher rates. This chasm concentrates an aging, shrinking population in the economic and political heart of the country, creating immense pressure on social services and the workforce.

In the United States, this urban-rural divide maps almost perfectly onto the political “red-blue” map. Higher-fertility states and counties are typically rural, more socially conservative, and vote Republican. Lower-fertility areas are overwhelmingly urban, more socially liberal, and vote Democratic. This demographic reality fuels the nation’s culture wars and amplifies the political weight of rural areas through systems like the Electoral College and the Senate, where demographic power doesn’t translate directly to political representation.

The Topography of Belief: Ethnic and Religious Divides

Deeper and often more volatile are the fault lines drawn by ethnicity and religion. When identity is tied to demography, population growth becomes a tool of cultural preservation and political power.

Nowhere is this demographic cartography more stark than in Israel. The country is a living laboratory of divergent fertility trends. Secular Jewish Israelis in Tel Aviv have fertility rates comparable to Europeans, around 2 children per woman. In contrast, the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) Jewish community has a fertility rate that hovers around 6.5—among the highest in the developed world. The Israeli-Arab population sits in between, with a rate that has been falling but remains above the secular Jewish average.

The political tremors from this fault line are undeniable. The rapidly growing Haredi population translates directly into more seats in the Knesset, granting their parties kingmaker status in coalition governments. This demographic weight drives national debates on everything from military conscription (from which Haredi men are largely exempt) to the definition of a Jewish state.

Travel across the globe to Nigeria, and a different fault line appears, this one mapping onto both religion and latitude. The predominantly Muslim north has one of the highest fertility rates in the world, often exceeding 6 or 7 children per woman in its rural expanses. The predominantly Christian south, more urbanized and with higher female education rates, has a significantly lower fertility rate, closer to 4. This north-south demographic imbalance strains Nigeria’s delicate political balance, which is unofficially predicated on power-sharing between the two regions. As the north’s population grows faster, it creates immense pressure for resource allocation, political representation, and jobs, fueling instability in a country already beset by challenges.

When Fault Lines Reshape the Political Map

These internal demographic shifts are not just academic curiosities; they are the leading indicators of future political conflict and transformation. When one group within a nation grows significantly faster than another, it inevitably alters the balance of power.

Consider India’s great north-south demographic divide. The prosperous, more educated southern states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu have fertility rates well below the replacement level. In contrast, the northern states of the “Hindi Belt”, such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, have much higher fertility rates. This has profound implications for India’s democracy. Seats in the Lok Sabha (India’s parliament) are allocated based on population. A future reallocation based on updated census data would dramatically shift political power from the south to the north, potentially creating a massive political crisis.

The consequences of these fault lines are far-reaching:

- Shifting Electorates: Groups with higher birth rates naturally see their share of the electorate grow over time, altering election outcomes for generations to come.

- Resource Competition: A region with a booming youth population will demand more schools and jobs, while a region with an aging population will need more healthcare and pensions. This pits regions and groups against each other in a zero-sum battle for state resources.

- Cultural Transformation: The “national character” is not static. The values, traditions, and languages of the most demographically dynamic groups will inevitably become more influential over time.

Looking at a simple national fertility rate tells you part of the story. But to truly understand the forces shaping a nation’s destiny, you must look deeper. You have to trace the invisible maps, identify the demographic tremors, and understand the fertility fault lines that lie just beneath the surface, slowly but surely remaking the world.