Take a moment and listen. Whether you’re in a bustling metropolis or a quiet town, you can likely hear it: the distant hum of traffic, the murmur of voices, the general thrum of human activity concentrated in one place. This soundscape is now the dominant auditory experience for our species. Sometime around 2008, humanity quietly crossed a monumental threshold. For the first time in our history, more people lived in urban areas than in rural ones. We officially entered the First Urban Century.

This isn’t just a dry statistic for demographers. It is a profound geographical event, a tectonic shift in how we occupy the Earth. The story of the 21st century is inextricably linked to the story of our cities—their explosive growth, their immense challenges, and their undeniable gravitational pull.

Mapping the Great Migration

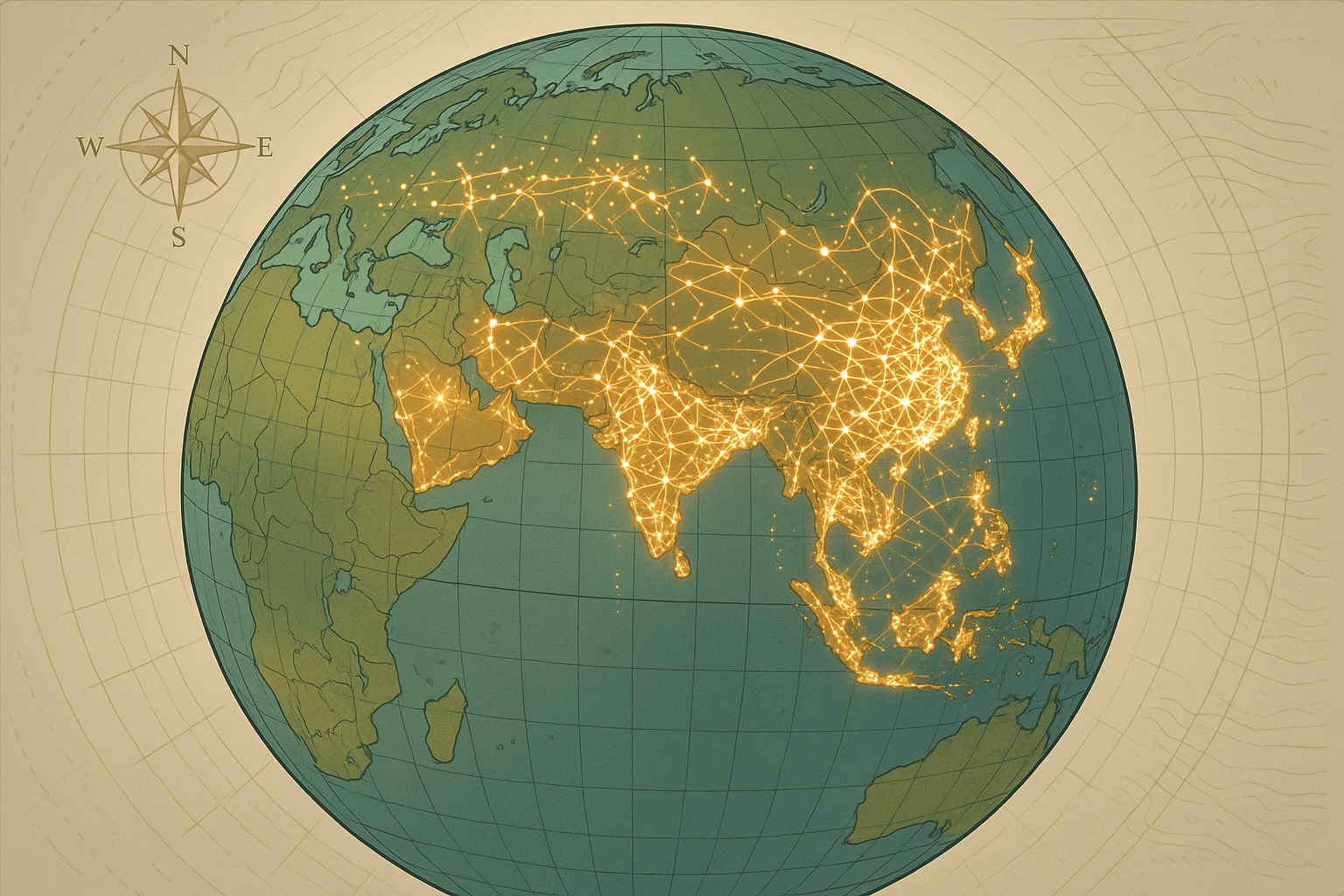

The speed of this transformation is staggering. In 1900, only about 13% of the world’s population lived in cities. By 1950, it was still less than a third. To go from 30% to over 50% in just a few decades represents the largest mass migration in human history. But this story has a distinct geography. While the cities of Europe and North America urbanized gradually over a century or more during the Industrial Revolution, today’s urban boom is overwhelmingly concentrated in Asia and Africa.

This is where the map of humanity is being redrawn. We are witnessing the rise of the megacity—an urban agglomeration with more than 10 million inhabitants. Think of Lagos, Nigeria, a city that has ballooned from just 300,000 people in 1950 to over 20 million today, and is projected to become the world’s largest city by 2100. Or consider the Pearl River Delta in China, a sprawling “meta-region” that links Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou into a continuous urban corridor home to nearly 70 million people. This is urbanization on a scale previously unimaginable.

The human geography behind this shift is driven by a powerful “pull.” Cities are magnets of opportunity. They offer the promise of jobs, better education and healthcare, and a connection to the global economy. For billions, the path out of rural poverty appears to be paved towards the nearest city.

The Physical Geography of Urban Life

Cities don’t just pop up randomly; their locations are deeply rooted in physical geography. It’s no coincidence that a vast number of the world’s largest cities are coastal. From Shanghai to Mumbai, New York to Rio de Janeiro, cities have historically thrived on access to waterways for trade and transport. They are nodes in a global network, and their prime locations on coasts and major rivers are a testament to geography’s enduring influence.

But as cities expand, they begin to rewrite the physical landscape themselves, creating entirely new geographical phenomena:

- Urban Heat Islands: Concrete, asphalt, and steel absorb and retain solar radiation far more effectively than natural vegetation. This causes cities to be several degrees warmer than their surrounding rural areas, altering local weather patterns and increasing energy demand for cooling.

- Sinking Ground: Many cities, like Jakarta, Mexico City, and Houston, are built on soft sediments and have relentlessly pumped groundwater to quench the thirst of their growing populations. The result is land subsidence—the ground beneath them is literally sinking, in some cases by several inches per year.

- Altered Waterways: We encase rivers in concrete channels, fill in wetlands to create new land, and build vast reservoirs hundreds of miles away, creating a city’s “hinterland” of resource dependency. The geographical footprint of a modern city extends far beyond its visible limits.

–

–

The Challenge: Building for Billions

This rapid, often unplanned, urbanization presents one of the greatest challenges of our time: how do we sustainably house and support billions of new city dwellers? The reality on the ground is often a stark contrast to the gleaming skylines seen in promotional photos.

For a significant portion of new urbanites, the city means life in an informal settlement. Slums, favelas, or shantytowns—whatever the local term, these areas are a defining geographical feature of the modern Global South city. Places like Kibera in Nairobi or Dharavi in Mumbai are home to hundreds of thousands of people living in densely packed conditions, often without access to reliable water, sanitation, or electricity. Yet, they are also places of incredible resilience, community, and informal economic dynamism. The challenge is not to erase them, but to integrate them into the formal city, providing essential services and secure land tenure.

Beyond housing, the strain on infrastructure is immense. Transport networks become gridlocked, water and energy systems are pushed to their limits, and waste management becomes a monumental task. For coastal cities, these pressures are compounded by the existential threat of sea-level rise—a direct clash between the physical geography of our planet and the human geography of our settlement patterns.

Forging a Sustainable Urban Future

The First Urban Century is at a crossroads. The path of sprawling, resource-intensive development that defined 20th-century cities is not sustainable on a planet with 8 billion people, heading towards 10 billion.

The future lies in rethinking the very nature of the city. Urban planners, geographers, and leaders are now focused on concepts like “smart growth” and “green infrastructure.” This means building denser, more compact cities that prioritize public transit over private cars. It means weaving nature back into the urban fabric with parks, green roofs, and permeable pavements to manage stormwater and combat the heat island effect. It means designing circular economies where waste is minimized and resources like water and energy are recycled and reused.

Our planet’s future will be won or lost in its cities. They are the primary source of our carbon emissions and environmental degradation, but they are also our greatest hope. By concentrating human ingenuity, creativity, and economic power, cities are the laboratories where we can forge the solutions for a sustainable and equitable world. How we choose to shape the physical and human geography of our cities in the coming decades will define the legacy of this, our First Urban Century.