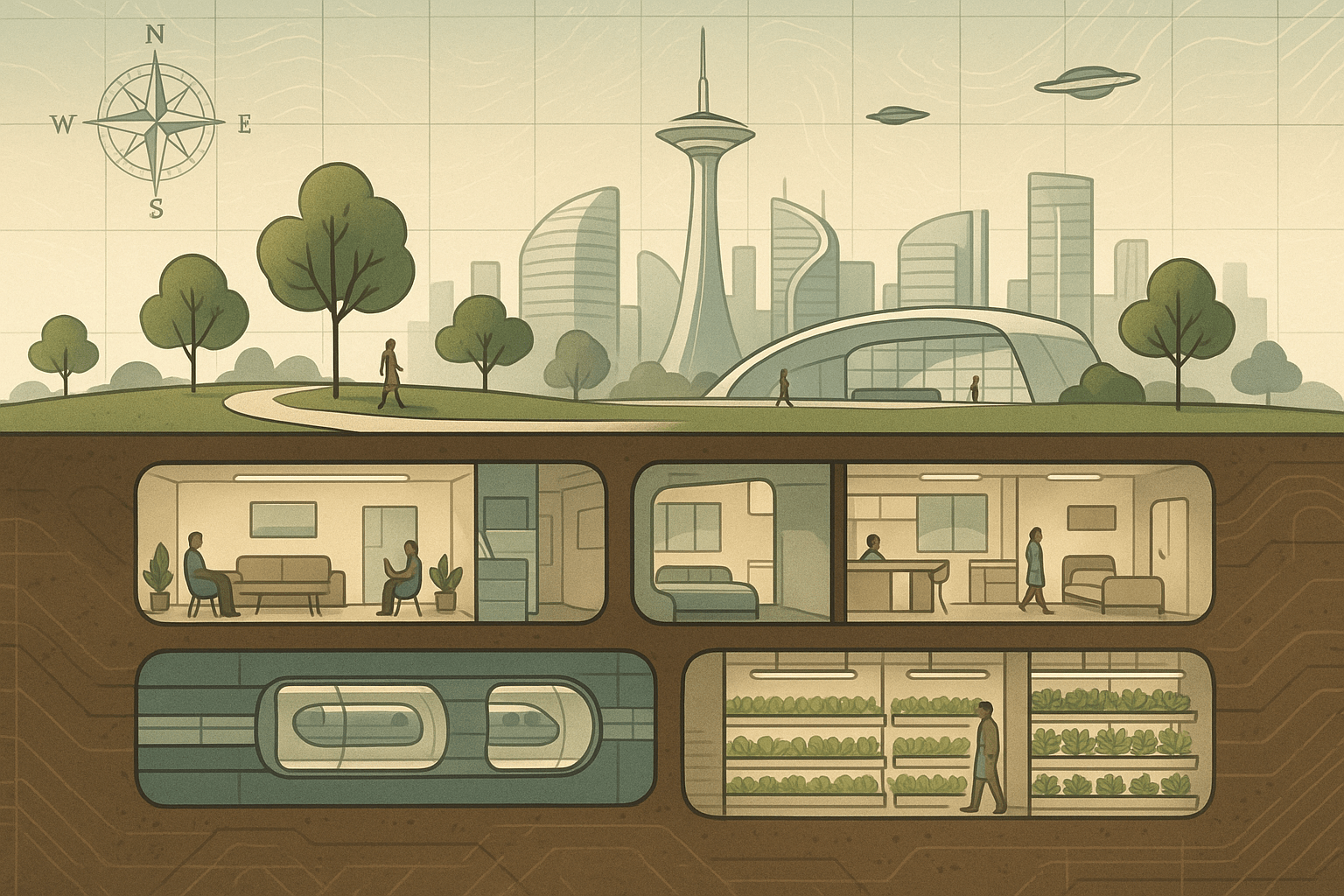

For centuries, the human story has been written on the surface of the Earth. We built our cities beside rivers, on coastal plains, and in sheltered valleys—our geography shaping our destiny. But as the 21st century unfolds, two powerful geographical forces are converging to push our ambitions in a new direction: down. The relentless growth of our urban populations is consuming finite land, while a changing climate unleashes ever-more-extreme weather. In response, architects, engineers, and urban planners are looking to a new frontier, one that has been beneath our feet all along.

The Geographical Pressures Pushing Us Down

The concept of subterranean living isn’t new. From the rock-hewn city of Petra in Jordan to the underground dwellings of Cappadocia in Turkey, our ancestors understood the protective embrace of the Earth. Today’s motivations, however, are driven by modern geographical crises.

First is the issue of human geography and urban density. Megacities like Singapore, Hong Kong, and Tokyo are struggling with profound land scarcity. Singapore, an island city-state with nearly 6 million people packed into just 734 square kilometers, has nowhere to expand but up or down. Building higher comes with its own limitations, making subterranean development a logical next step to reclaim precious surface area for housing, parks, and public life.

Second is the challenge of physical geography and climate. In places like Dubai, summer temperatures can make surface life unbearable. Conversely, in cities like Montreal, harsh winters drive activity indoors. The Earth’s crust offers a remarkable solution: natural geothermal insulation. Just a few meters below ground, the temperature remains relatively stable year-round, drastically reducing the energy needed for heating and cooling. This makes underground structures inherently resilient to heatwaves, blizzards, and even tornados.

Modern Pioneers of the Underworld

While fully self-contained subterranean cities remain largely theoretical, several places around the world offer a glimpse into this underground future, each uniquely shaped by its local geography.

Montreal’s RÉSO: The Climate Solution

Montreal’s “underground city”, officially known as RÉSO (the French word for network), is one of the world’s most extensive subterranean complexes. Spanning over 32 kilometers, it connects metro stations, shopping malls, hotels, universities, and residential buildings. Its existence is a direct response to Montreal’s geography—specifically, its continental climate, which brings humid, hot summers and long, frigid winters. The RÉSO allows life to continue, unimpeded and comfortable, regardless of the weather raging on the surface.

Helsinki’s Granite Foundation

The Finnish capital has a master plan for its own subterranean expansion, and its success is owed entirely to its underlying physical geography. Helsinki is built on a foundation of ancient, incredibly stable granite bedrock. This geological gift makes large-scale excavation safe and cost-effective. The city has already carved out over 400 structures from the rock, including a swimming pool complex (Itäkeskus swimming hall), a church (Temppeliaukio Church), and even data centers that are cooled by the naturally low temperatures of the rock.

Singapore’s Subterranean Master Plan

For Singapore, going underground is a matter of national survival. With no room for sprawl, the government has developed a Subterranean Master Plan to systematically move infrastructure and utilities below ground. This includes warehousing, water reclamation facilities, ammunition storage, and transportation networks. The goal is strategic: free up valuable surface land for people. By placing the functional, industrial parts of the city out of sight, Singapore can create a greener, more livable environment on the surface—a perfect example of human geography adapting to physical constraints.

Coober Pedy’s Dugouts: Vernacular Architecture

Not all subterranean living is high-tech. In the heart of the South Australian Outback lies Coober Pedy, an opal-mining town where summer temperatures regularly exceed 45°C (113°F). For a century, residents have escaped the brutal heat by living in “dugouts”—homes burrowed into the hillsides. These residences maintain a comfortable, stable temperature year-round without air conditioning. Coober Pedy is a testament to how subterranean living can be a low-tech, sustainable response to an extreme climate.

The Rock and the Hard Place: Overcoming Subterranean Challenges

Building a city underground is more complex than simply digging a hole. The challenges are immense, spanning the fields of geology, psychology, and urban planning.

- Geological Stability: As Helsinki proves, the right geology is critical. Building in seismic zones like those in Japan or California presents enormous engineering hurdles. Likewise, soft, sandy, or water-logged soil makes excavation dangerous and expensive. A deep understanding of the local physical geography is the first and most important step.

- Hydrology and Air: How do you manage groundwater and prevent flooding? How do you pump a constant supply of fresh, clean air deep underground for thousands of people? Solving these life-support challenges requires sophisticated and energy-intensive systems.

- The Psychology of a Windowless World: Humans have a deep-seated need for nature and sunlight—a concept known as biophilia. Living without a view of the sky or a connection to the daily cycle of light and dark can lead to depression and disorientation. Architects are exploring solutions like “virtual skylights”, light-funneling fiber optics, and vast atriums that bring a sense of the surface world down below.

- Social Geography: A darker question looms. Will subterranean spaces create a new form of social stratification? The dystopian vision is one where the wealthy enjoy the sunlit surface while the poor, or essential services, are relegated to the depths. Planners must consciously design these spaces to be equitable and desirable for all.

The Future is an Iceberg

The future may not be a complete migration into cavernous, self-contained cities. Instead, we are more likely to see the rise of “iceberg cities”—metropolises where a significant and seamlessly integrated portion of their functions occurs below ground. Transport, logistics, utilities, and even certain commercial activities will dive deep, leaving the surface freer, greener, and more focused on human well-being.

The push downward is not a rejection of the world above, but an attempt to preserve it. By strategically using the space beneath our feet, we can alleviate the geographical pressures that threaten our surface cities. The next great frontier of urban geography may not be expanding outward into the wilderness, but plunging inward into the very earth we stand on.