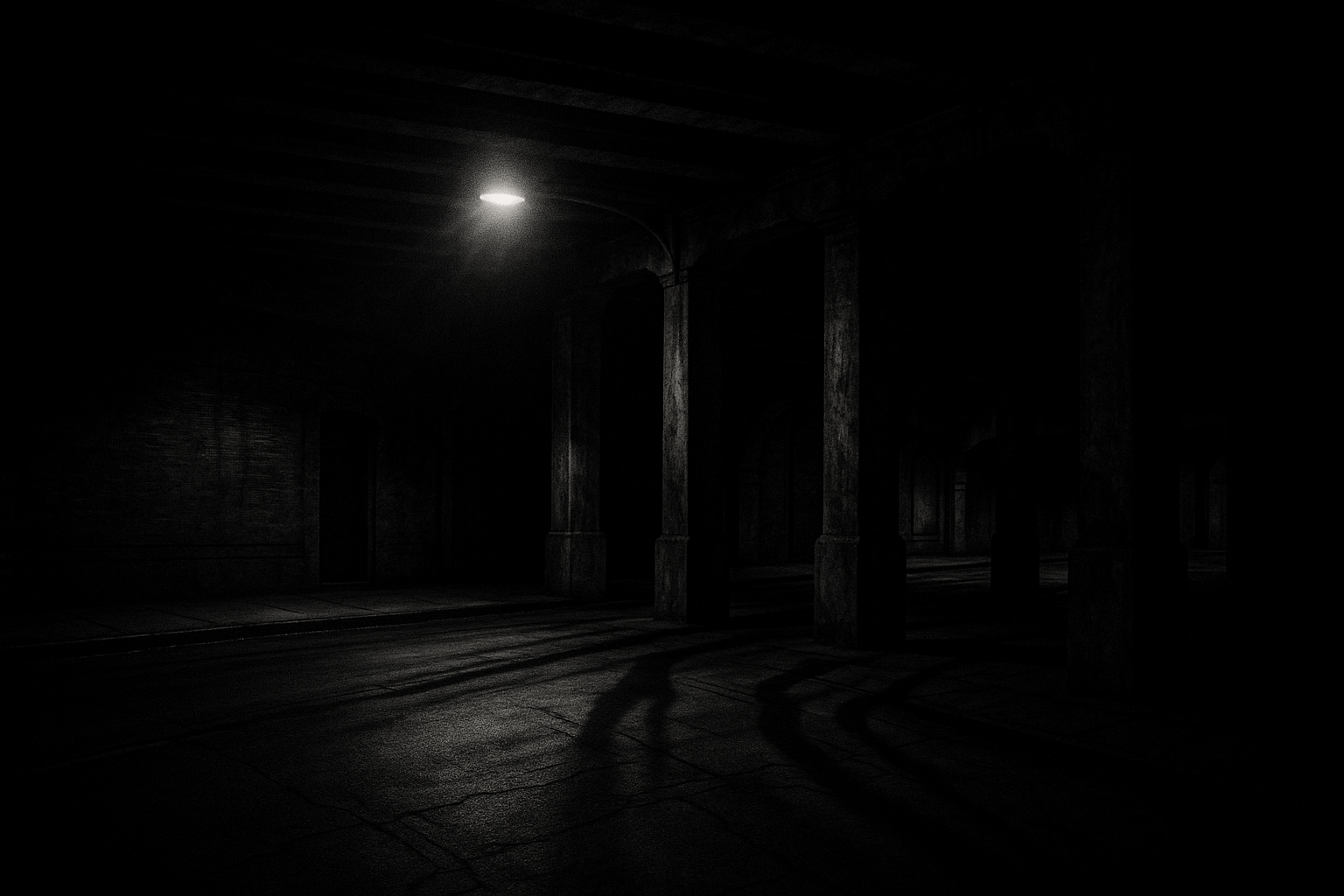

Have you ever chosen the long way home, deliberately avoiding that poorly lit underpass or the park that’s a little too quiet after sunset? Have you felt a prickle of unease on a deserted platform, listening for footsteps that aren’t your own? This feeling isn’t just paranoia; it’s a deeply geographical experience. It’s an internal map of perceived danger, charted not by lines of latitude and longitude, but by shadows, silence, and sightlines. This phenomenon has a name: the Geography of Fear.

It’s a concept that moves beyond crime statistics to explore how the physical design of our urban environment directly influences our sense of safety, dictating where we feel welcome and where we feel vulnerable. It’s the intersection of physical geography—the concrete, steel, and green spaces of a city—and human geography—our emotional and psychological response to those spaces.

What Are Landscapes of Fear?

Coined by the renowned geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, the term describes how certain environments can evoke anxiety and fear, regardless of the actual, statistical risk of harm. A city’s “landscape of fear” is composed of places that feel uncontrolled, unobserved, and unpredictable. These are not necessarily the most crime-ridden areas, but they are the ones that our instincts tell us to avoid.

This fear is often a rational response to specific environmental cues. Our brains are wired for survival, constantly scanning our surroundings for potential threats. When the urban landscape provides signals of decay, isolation, or concealment, our internal alarm bells start to ring. It’s a silent conversation between our senses and the city’s structure.

The Anatomy of an Unsafe Space

What specific elements turn a simple street or park into a geography of fear? Urban planners and criminologists have identified several key features that contribute to this perception of danger. These are the building blocks of an unsafe space:

- Poor Lighting: This is the most classic element. Darkness is a powerful amplifier of fear because it conceals potential threats and robs us of our primary sense for detecting danger—our sight. A single broken streetlight can render an entire block a no-go zone in our mental map.

- Lack of “Eyes on the Street”: Famed urbanist Jane Jacobs championed this concept. Spaces feel safer when they are subject to natural surveillance from people living, working, and walking by. Blank walls, shuttered storefronts, and high fences create dead zones where a person can feel utterly alone and unobserved, making them feel more vulnerable.

- Obstructed Sightlines and Entrapment Spots: Our fear spikes when we can’t see what’s ahead or when our escape routes are cut off. Blind corners, overgrown shrubbery, narrow and winding alleys, and subterranean walkways all create a sense of potential ambush or entrapment.

- Signs of Decay and Incivility: The “Broken Windows Theory” suggests that visible signs of neglect—such as graffiti, litter, abandoned buildings, and vandalism—signal a breakdown in social order. These elements tell us that a space is not cared for or controlled, which we interpret as a sign that illicit activities may be tolerated there.

- Monofunctional Zones: Areas designed for a single purpose, like a central business district full of offices or a large park with no surrounding residences, become predictably empty at certain times. This desolation can transform a bustling daytime area into an intimidating, empty expanse at night.

The Human Geography of Fear: An Unequal Burden

Crucially, the geography of fear is not experienced uniformly by everyone. Our individual identities—our gender, age, race, sexuality, and physical ability—profoundly shape how we navigate and perceive the city.

For example, women and gender-diverse individuals often carry a heightened sense of vigilance, conditioned by the threat of gender-based violence. A poorly lit street may be an inconvenience for one person but a terrifying barrier for another. This fear has tangible consequences: it restricts mobility, limits access to jobs and recreation, and effectively shrinks the city for those who feel most at risk. An elderly person may avoid uneven pavements for fear of falling, while a person of color may feel unsafe in neighborhoods with a history of racial profiling. In this way, poor urban design becomes an issue of social equity, limiting the “right to the city” for its most vulnerable inhabitants.

Designing for Safety: Urban Planning as an Antidote

If poor design can create landscapes of fear, then thoughtful design can dismantle them. The goal is not to build fortresses, but to cultivate environments that feel naturally safe and welcoming. This is the core idea behind Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED), a set of principles used by planners and architects worldwide.

Natural Surveillance

Instead of relying solely on security cameras, CPTED prioritizes maximizing visibility. This means using low-level landscaping so people can see over it, installing ample, human-scale lighting, and designing buildings with windows facing the street. Mixed-use zoning is a powerful tool here; by placing cafes, shops, and apartments side-by-side, we ensure there are “eyes on the street” at all hours of the day.

Natural Access Control

This isn’t about building walls, but about using design to guide people intuitively. Clearly defined pathways, low fences, and distinct entryways create a sense of order and make it harder for potential offenders to approach a target without being noticed. It channels human flow in a way that feels open but organized.

Territorial Reinforcement

Spaces feel safer when it’s clear someone owns and cares for them. This principle encourages a sense of community ownership. Public art, well-tended community gardens, clean sidewalks, and distinctive neighborhood banners all send a powerful message: “people care about this place.” This fosters a collective sense of responsibility and deters would-be criminals, who feel more like outsiders in a well-tended space.

Maintenance and Management

This is the long-term commitment to safety. A beautifully designed park can quickly become a landscape of fear if it’s not maintained. This means promptly replacing burnt-out lightbulbs, removing graffiti, repairing broken benches, and keeping the space clean. Good maintenance is the ultimate signal of a competent, caring authority and an engaged community.

Ultimately, the geography of fear is a solvable problem. By understanding how the physical form of our cities shapes our deepest instincts, we can begin to design, build, and retrofit them for everyone. A truly great city isn’t just one with impressive skylines or efficient transport; it’s one where every resident, regardless of who they are, can walk home after dark feeling not fear, but a sense of belonging.