This isn’t just an astronomical curiosity; it’s a powerful force in both physical and human geography. By turning down the sun’s energy output, even slightly, these events have cooled the planet, redrawn maps, and redirected the course of human history.

What is a Grand Solar Minimum?

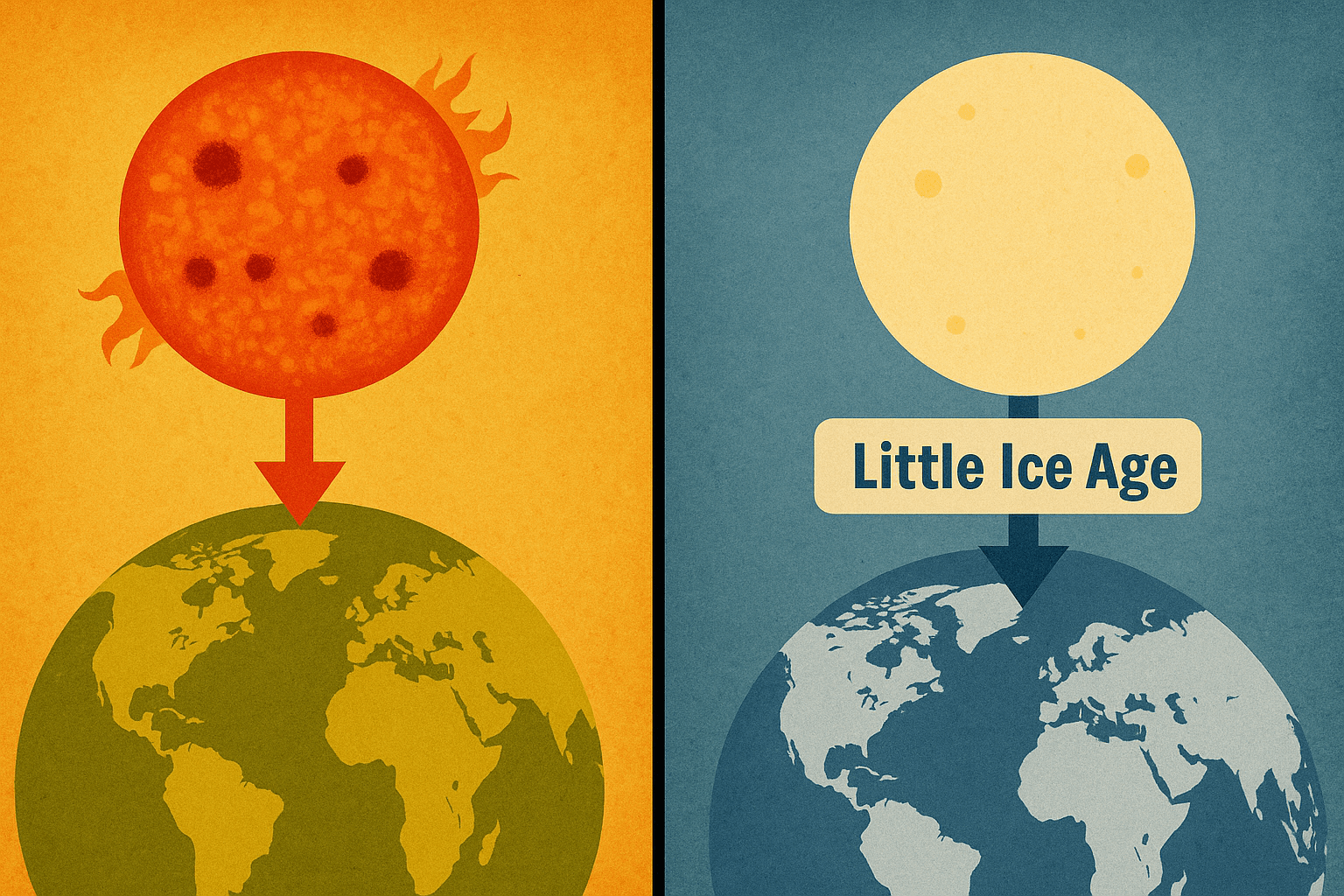

A Grand Solar Minimum is essentially a multi-decade period where successive solar cycles are exceptionally weak. Sunspot activity, a key indicator of the sun’s magnetic energy, all but disappears. This reduction in activity leads to a slight decrease in the sun’s Total Solar Irradiance (TSI)—the total amount of solar energy reaching Earth’s upper atmosphere.

While the drop in TSI is small (around 0.1% to 0.3%), the planet’s climate system is incredibly sensitive. This small change, especially when combined with other climatic factors like volcanic activity, can act as a powerful regional cooling trigger. The most famous of these events is the Maunder Minimum (c. 1645-1715), a period that coincided with the most intense phase of the “Little Ice Age.”

Mapping the Maunder Minimum: A Frozen World

The Maunder Minimum offers a vivid case study in how a quiet sun reshapes physical geography. The cooling was most pronounced in the Northern Hemisphere, particularly in Europe, leaving a trail of dramatic environmental changes.

- Frozen Rivers and Seas: The iconic image of this era is the frozen River Thames in London. For decades, the river froze solid for weeks at a time, hosting elaborate “Frost Fairs” with shops, pubs, and even elephant parades on the ice. Similarly, the canals of Amsterdam and other Dutch cities froze regularly, making ice skating a vital mode of transport. The Baltic Sea froze over completely on several occasions, allowing armies and merchants to travel on ice between Sweden, Denmark, and Poland—a geographical impossibility today.

- Advancing Glaciers: In the Alps, glaciers surged forward at an alarming rate. Swiss and French farming villages that had existed for centuries were consumed by advancing ice. In the Chamonix Valley in France, the Mer de Glace glacier advanced by over a kilometer, threatening local communities and destroying farmland.

- North American Hardship: Across the Atlantic, the changes were also felt. Early European colonies experienced brutally long and cold winters. New York Harbor reportedly froze over, allowing people to walk from Manhattan to Staten Island. These harsh conditions severely tested the resilience of early settlers and altered agricultural possibilities.

The Human Geography of a Colder Climate

These shifts in physical geography had immediate and severe consequences for human populations, fundamentally altering patterns of life, settlement, and survival.

Agriculture, Famine, and Migration

The most direct impact was on agriculture. Shorter, cooler, and wetter growing seasons led to widespread crop failures across Europe. Wheat and oat harvests failed repeatedly from Scotland to Italy. Vineyards that had thrived in southern England during the preceding Medieval Warm Period withered and disappeared. In Iceland, cereal cultivation became impossible, and the island’s population was pushed to the brink of starvation, becoming almost entirely dependent on fishing and imports.

This agricultural crisis triggered famine, malnutrition, and disease, which in turn fueled social unrest and migration. Historians often link the extreme climate of the 17th century to the period known as the “General Crisis”, a time of widespread political instability, rebellion, and warfare across Eurasia, including the Thirty Years’ War. While not the sole cause, the constant stress of food scarcity undoubtedly exacerbated existing political tensions.

Cultural and Societal Shifts

The cold also seeped into the culture. The era gave rise to a new genre of art: the Dutch winter landscape. Painters like Hendrick Avercamp and Aert van der Neer became famous for their detailed, sprawling canvases depicting communities skating, working, and socializing on frozen waterways. These paintings are a direct cultural record of a changed climate.

Innovation also followed hardship. The Dutch refined the design of the ice skate, adding a bladed edge that made it an efficient tool for travel and commerce. Architecture began to adapt, with greater emphasis on smaller windows and larger fireplaces to conserve heat.

Beyond the Maunder: Other Minimums, Other Geographies

The Maunder Minimum wasn’t an isolated incident. Other solar lulls have left their mark on the map.

- The Spörer Minimum (c. 1460-1550): This earlier cold snap is strongly linked to one of human geography’s great tragedies: the end of the Norse settlement in Greenland. As sea ice expanded and growing seasons vanished, the European colony became isolated and unsustainable. Its last inhabitants perished, a stark example of a community erased by climate change.

- The Dalton Minimum (c. 1790-1830): This more recent and less severe minimum also brought a period of global cooling. It coincided with the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, which led to the catastrophic “Year Without a Summer” in 1816. The underlying cooling from the Dalton Minimum likely amplified the volcanic winter, causing snow in June in North America and Europe, triggering a global food crisis, and inspiring Mary Shelley’s gothic masterpiece, Frankenstein, during a gloomy, storm-wracked Swiss holiday.

The Sun’s Role in Modern Geography

Today, scientists watch the sun’s cycles with intense interest. Some solar physicists suggest we may be entering another prolonged period of low solar activity, a potential modern Grand Solar Minimum. However, it is crucial to place this in the context of our modern world.

The scientific consensus is clear: any cooling effect from a new solar minimum would be far outweighed by the warming caused by human greenhouse gas emissions. It would not trigger a new Little Ice Age. Instead, it might temporarily slow the rate of global warming by a few tenths of a degree, a minor speed bump on a powerful upward trend. The geography of our future is being written not just by the sun, but by the complex interplay between natural cycles and unprecedented human influence.

By studying the geography of past solar minimums, we gain a profound appreciation for our planet’s sensitivity. The sun is not merely a passive backdrop to human affairs; it is an active, dynamic force that has helped sculpt our landscapes, test our resilience, and shape the very map of our world.