Imagine buying a house for the price of a used refrigerator. Or better yet, getting one for free. This isn’t a scam or a fantasy; it’s a tangible reality in the shrinking towns and villages of Japan. The country is grappling with a peculiar crisis: a surplus of more than 8 million empty and abandoned homes known as akiya (空き家). In response, local governments have rolled out an intriguing solution: “Akiya Banks”, databases of these vacant properties designed to lure new life into hollowed-out communities.

But the story of Japan’s ghost houses isn’t just about economics or real estate. It’s a compelling tale written on the nation’s very landscape. The spread of akiya is a geographical phenomenon, one deeply rooted in the interplay between Japan’s physical terrain and its dramatic human and demographic shifts.

The Human Geography of Absence

To understand where akiya come from, we first need to look at the human forces that have reshaped Japan over the last century. The primary driver is a demographic one-two punch: one of the world’s lowest birth rates combined with the world’s longest life expectancy. With fewer people being born and the elderly population growing, the country’s total population is in a state of steady decline. There are simply not enough people to fill the homes left behind.

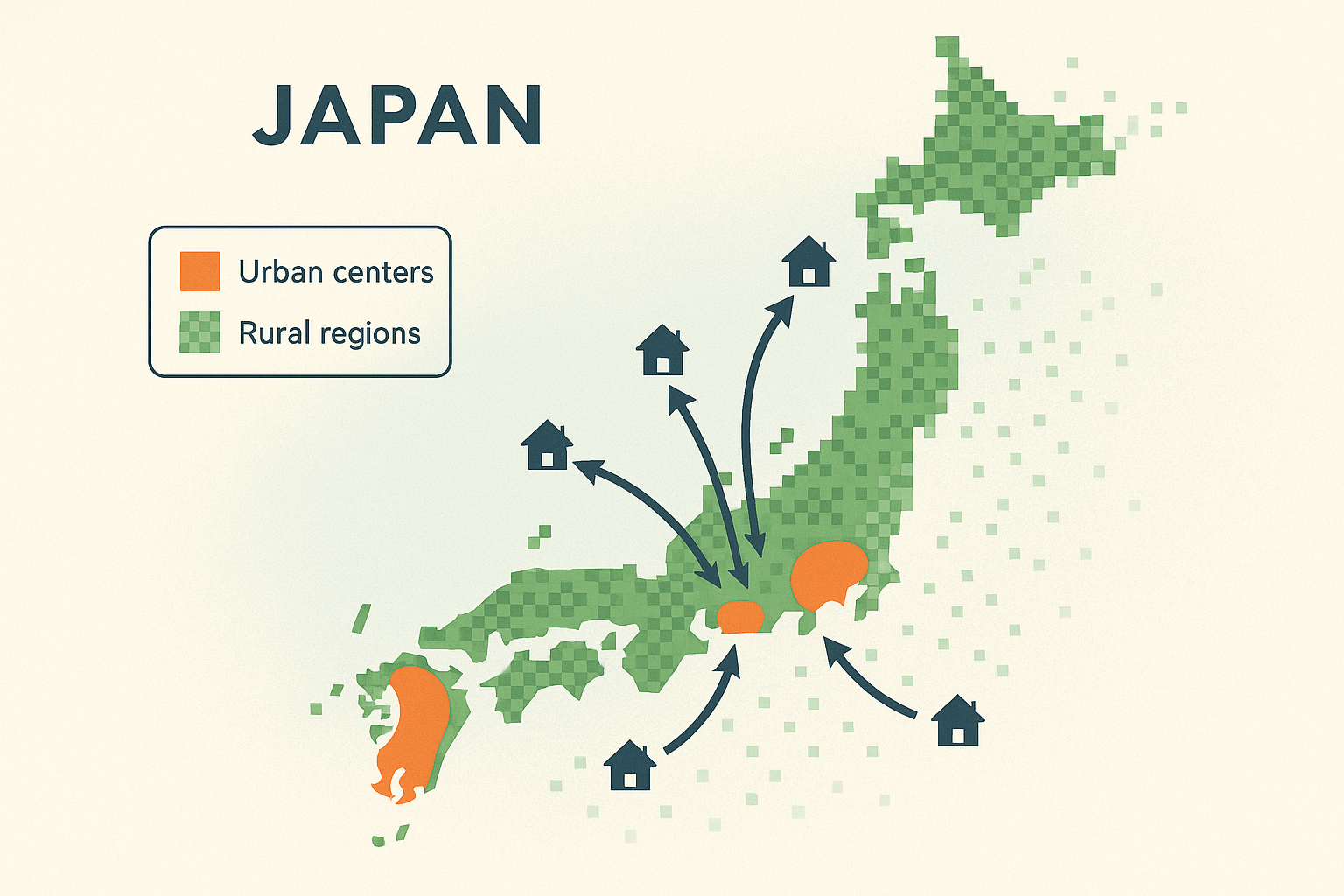

This demographic tide was channeled by a massive wave of internal migration. Following World War II, Japan’s economic miracle created an irresistible pull towards its coastal cities. Young people from rural, inland communities flocked to the sprawling metropolitan areas of Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya for education and, most importantly, jobs. They built new lives and new families in the city, leaving their ancestral homes in the countryside, or inaka, to their aging parents.

When these parents passed away, their city-dwelling children inherited properties they had no use for. This is where cultural and economic geography collide:

- The Burden of Inheritance: A rural house miles from one’s job is a liability, not an asset. It comes with annual property taxes, maintenance costs, and the responsibility of upkeep. Tearing it down is expensive, so the most economically rational choice is often to do nothing—to simply let it sit empty.

- The Stigma of “Used” Homes: Unlike in many Western cultures, in Japan there is a strong preference for new construction. Second-hand homes depreciate rapidly. This is compounded by a cultural superstition against buying homes where a previous owner has died, especially if it was a “lonely death”, or kodokushi—an increasingly common tragedy in an aging society.

The result is a landscape dotted with homes frozen in time, slowly being reclaimed by nature, a physical testament to a generation that moved away and never came back.

The Physical Landscape of Emptiness

The distribution of akiya across Japan is far from random. It follows the contours of the country’s challenging physical geography. Japan is a nation of mountains; roughly 73% of its landmass is mountainous and largely unsuitable for large-scale development. For centuries, communities thrived in river valleys and small coastal plains, but modern economic logic favors consolidation and connectivity.

Today, the akiya “belt” lies precisely in these geographically isolated regions. Prefectures in the mountainous, less-connected islands of Shikoku (like Tokushima and Kochi) and the Chugoku region of western Honshu (like Shimane and Yamaguchi) have some of the highest rates of vacant homes in the country. These are places of stunning natural beauty, but their steep terrain makes modern infrastructure difficult and expensive. For young people, it means long commutes, fewer high-paying jobs, and limited access to universities and specialized medical care.

Furthermore, Japan’s position on the Pacific Ring of Fire adds another layer of geographical risk. The constant threat of earthquakes, typhoons, and landslides makes older, wooden-frame akiya a significant hazard. Many of these homes were built before modern seismic codes were enacted. To bring an old kominka (traditional house) up to code is a monumental expense, far exceeding the property’s market value. After a natural disaster, it’s often easier and safer for owners to abandon the property altogether than to face the cost and risk of rebuilding. The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, for example, accelerated abandonment in affected rural areas, leaving behind not just damaged homes but also entire communities deemed too risky for repopulation.

Akiya Banks: An Experiment in Reshaping the Map

Facing this hollowing out of the countryside, municipal governments created Akiya Banks. These are essentially real estate listings, run by the town hall, that showcase available empty homes. The prices are often astonishingly low—$25,000, $5,000, or even free—provided the new owners commit to renovating and living in the property, thereby contributing to the local tax base and community life.

The goal of the Akiya Bank program is nothing short of demographic engineering: to reverse the flow of migration and repopulate the countryside. They are a deliberate attempt to redraw Japan’s population map. The target audience is diverse: young families seeking a lower cost of living, retirees looking for a quiet life, artists and artisans in search of cheap studio space, and, increasingly, foreigners enchanted by the ideal of a traditional Japanese lifestyle.

The rise of remote work, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has given this experiment a new tailwind. What was once a geographical barrier—isolation—can now be a selling point. The dream of swapping a cramped Tokyo apartment for a spacious rural house with a garden is more attainable than ever.

However, the challenges remain immense. The “free” house is just the beginning. Renovation costs can easily run into the tens of thousands of dollars. Local job markets are still thin, and integrating into a small, tight-knit, and aging community can be socially difficult for outsiders (yosomono). The same geographical factors that created the akiya problem—physical isolation and lack of economic gravity—are the very obstacles new residents must overcome.

Ultimately, Japan’s akiya are more than just empty buildings. They are the physical scars of profound demographic shifts, etched onto a challenging and dynamic landscape. The Akiya Banks that seek to fill them are a bold and fascinating experiment in social geography. Whether they can truly revitalize rural Japan or are merely a small patch on a much larger problem remains to be seen, but their existence tells a powerful story about a nation attempting to consciously re-inhabit its own geography.