The Lines on the Map That Breathe: Charting the Geography of Sacred Trails

A path is more than just a way to get from A to B. For millennia, some paths have been imbued with a deeper purpose, drawing millions of feet along their course not for trade or conquest, but for faith, penance, and enlightenment. These are the world’s great pilgrimage routes, from the sun-baked plains of Spain to the misty mountains of Japan. But to see them merely as spiritual highways is to miss their most profound story: the intimate, powerful dialogue they have with geography itself.

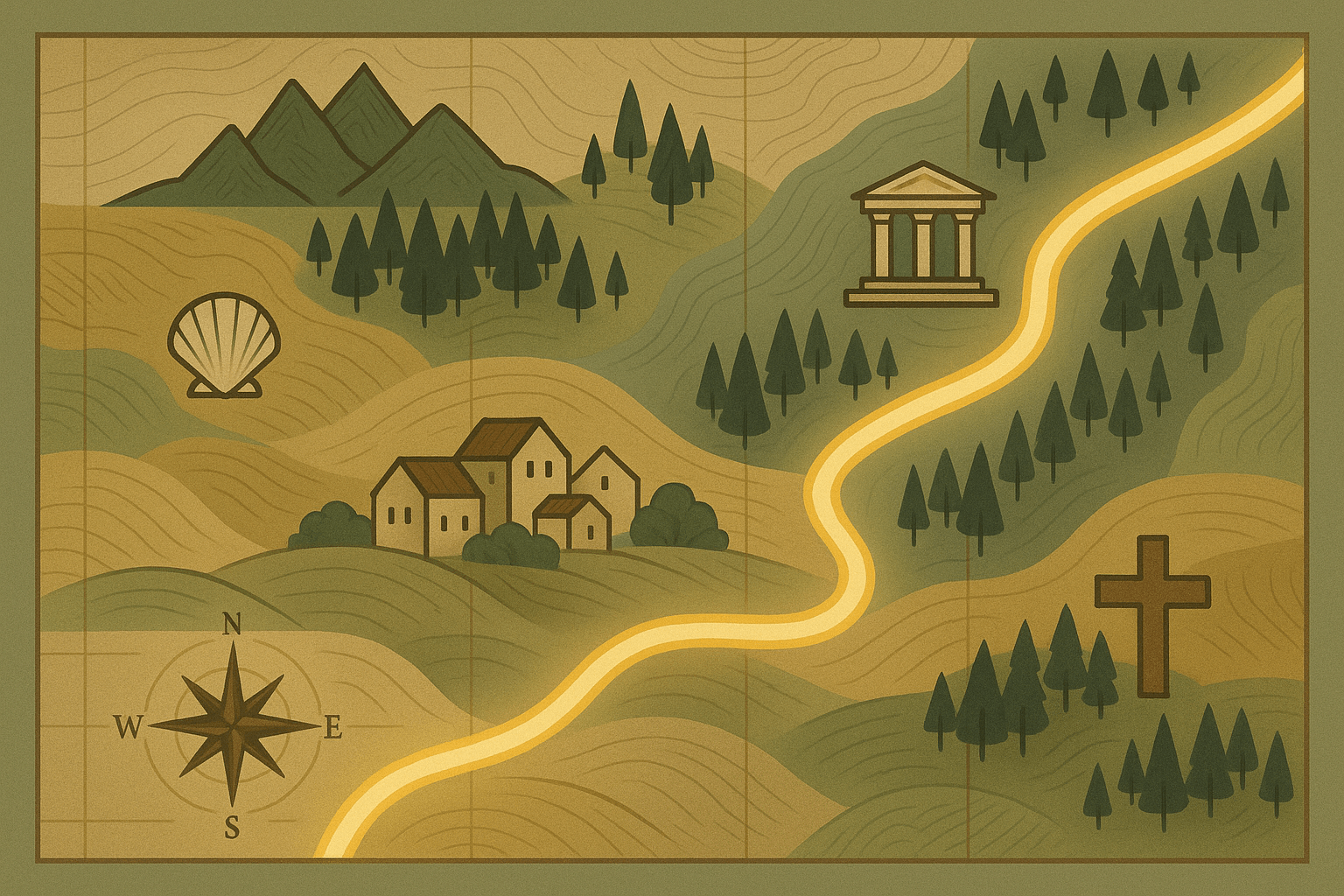

Pilgrimage routes are not random lines drawn on a map. They are deeply geographical phenomena, shaped by the contours of the Earth and, in turn, reshaping the human and physical landscapes they traverse. To walk them is to read a story written in mountains, rivers, cities, and stones.

The Spatial Logic of a Sacred Journey

Why does a pilgrimage route run where it does? The answer lies in a combination of physical necessity and spiritual significance, a concept we can call “sacred spatial logic.”

First and foremost, these routes are governed by physical geography. Early pilgrims were travelers on foot, and their paths followed the logic of least resistance. They traced the gentle gradients of river valleys, like the segments of the Via Francigena that follow the Rhône. They sought out natural mountain passes, like the treacherous Great St. Bernard Pass in the Alps or the Roncesvalles Pass in the Pyrenees, a dramatic entry point for the Camino Francés into Spain.

The destinations themselves are often tied to specific geographical features:

- Mountains: The arduous trek to Mount Kailash in Tibet or Mount Sinai in Egypt ties the physical challenge of the ascent to the spiritual goal.

- Rivers: The Char Dham Yatra in the Indian Himalayas leads to the sources of four holy rivers, including the Ganges. The river itself becomes a flowing, linear destination.

- Springs & Grottoes: The site of Lourdes in France is centered on a grotto and spring, a specific hydrogeological feature believed to possess miraculous properties.

Layered on top of this physical foundation is the human geography of faith and survival. Routes naturally connect nodes of human activity. The Camino de Santiago, for instance, is not a single path but a vast network (a red de caminos) that consolidated over centuries, funneling pilgrims from across Europe towards the tomb of St. James. Many of its Spanish sections were laid directly over old Roman roads, co-opting existing infrastructure for a new, sacred purpose. The path connects a string of cities—Pamplona, Burgos, León—that grew into vital hubs of religious and economic power, their very existence defined by the river of people flowing through them.

Landscapes Forged by Faith: The Pilgrim’s Infrastructure

A constant stream of travelers over centuries leaves an indelible mark on the landscape. The human geography along a major pilgrimage route evolved into a highly specialized support system—a service economy for the soul, built of stone, timber, and tradition.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the settlements along the way. Towns like Puente la Reina in Spain owe their existence to the Camino. Its name, “the Queen’s Bridge”, refers to the magnificent 11th-century Romanesque bridge built specifically to allow pilgrims to cross the River Arga. Many of these “Camino towns” have a distinct linear morphology, their main street one and the same as the pilgrim’s path.

This purpose-built landscape includes:

- Shelter: The famous albergues (pilgrim hostels) of the Camino, the shukubo (temple lodgings) on Japan’s Shikoku Pilgrimage, and the ancient caravanserais of the Middle East provided safe lodging.

- Wayfinding: Simple, brilliant geographical markers guide the way. The scallop shell, an icon of the Camino, is embedded in sidewalks and on posts for hundreds of miles. On Japan’s Kumano Kodo, small, moss-covered Oji shrines serve as spiritual signposts and rest stops, while Jizo Bodhisattva statues comfort and protect travelers.

- Engineering: Beyond bridges, the landscape is physically engineered. The Kumano Kodo features miles of ishidatami, beautifully laid stone steps that make the steep, rain-slicked mountain slopes of the Kii Peninsula navigable.

This infrastructure created a unique economic geography. A symbiotic relationship formed between the travelers and the settled communities, who provided food, shelter, spiritual guidance, and even the earliest forms of souvenirs, like pilgrim badges and relics.

The Modern Resurgence: Old Paths, New Geographies

In the 21st century, these ancient routes are experiencing a dramatic revival, but the geography of the journey is changing once again. Today’s pilgrim is a far more global and diverse figure. They may be walking for faith, but just as often they are seeking adventure, fitness, cultural immersion, or a “digital detox”—a conscious disconnection from modern life by engaging in the simple, physical act of walking.

This resurgence is creating a new human geography along the paths. The influx of international travelers transforms the cultural landscape. English, German, and Korean are heard as often as Spanish in the villages of Galicia. This has profound economic consequences. For many declining rural areas, the modern pilgrimage is a lifeline, revitalizing local economies through tourism. However, this boom is a double-edged sword, bringing challenges of overcrowding, commercialization, and environmental strain, forcing a debate about how to preserve the “authenticity” of the experience.

Technology has also altered the pilgrim’s interaction with the physical world. GPS devices, booking apps, and online forums are the new, invisible infrastructure. While this makes the journey more accessible and safer, it fundamentally changes the nature of navigation and discovery. Getting lost and finding one’s way through observation and instinct—once a core part of the geographical experience—is becoming a rarer event.

In response, a new layer of global geography has been added: institutional protection. The recognition of routes like the Camino de Santiago and the Kumano Kodo as UNESCO World Heritage Sites formalizes their global importance, providing resources for conservation and ensuring that the physical path and its cultural landscape endure.

From a mountain pass dictating a detour to a town that owes its entire existence to a bridge, the geography of pilgrimage is a powerful reminder that our movements and our beliefs are written into the very fabric of the planet. These routes are not relics of the past. They are living, breathing cultural landscapes, a testament to the enduring human need to place one foot in front of the other and walk toward something that matters, reading the map of the Earth with every step.