UXO refers to any type of explosive weapon—bombs, shells, grenades, landmines, cluster munitions—that did not explode when it was employed and still poses a risk. These ghosts of conflict create invisible borders, dictate where people can live and farm, and hold development hostage. To understand their impact, we must first map their presence.

The Global Footprint of a Deadly Legacy

While the problem is global, the contamination is intensely concentrated in the theaters of 20th and 21st-century conflicts. The map of UXO is a tragic atlas of modern warfare:

- Southeast Asia: Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam are profoundly scarred by the Vietnam War era. The sheer volume of ordnance dropped here is staggering.

- Europe: The fields of France and Belgium still yield an “iron harvest” from World War I. The Balkans, particularly Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, are littered with mines and cluster munitions from the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s.

- The Middle East & North Africa: Decades of conflict have left countries like Iraq, Syria, Libya, and Yemen saturated with UXO, complicating humanitarian aid and post-conflict reconstruction.

- Africa: Angola, Mozambique, and Chad face extensive contamination from long civil wars, denying communities access to vital agricultural land and water sources.

- South America: Colombia is one of the most mine-affected countries in the world, a legacy of its long internal conflict between the government and guerrilla groups.

Each of these regions tells a unique story of conflict, but they share a common geographical consequence: the land itself has become an enduring enemy.

A Scar on the Land: Laos, The World’s Most Bombed Nation

To truly grasp the scale of the UXO crisis, we must travel to Laos. Between 1964 and 1973, during a “Secret War” conducted by the U.S. as an extension of the Vietnam War, more bombs were dropped on this small, landlocked nation than were dropped on all of Europe during World War II. The primary target was the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a crucial supply line for North Vietnamese forces that snaked through the rugged eastern provinces of Laos.

The numbers are almost incomprehensible: an estimated 270 million cluster submunitions were dropped. With a failure rate of up to 30%, this left as many as 80 million live “bombies” scattered across the landscape. The geography of this bombing campaign is key.

The eastern provinces, like Xieng Khouang and Savannakhet, bore the brunt of the assault. The physical geography of this region—characterized by mountains, dense forests, and rice paddies—makes detection and clearance exceptionally difficult. Bombs burrowed into the soft earth of farmland, were concealed by jungle canopy, and were washed by monsoonal rains into rivers and fields far from their original drop point. The famous Plain of Jars, an ancient archaeological site and a vital agricultural hub in Xieng Khouang, is one of the most heavily contaminated areas on Earth.

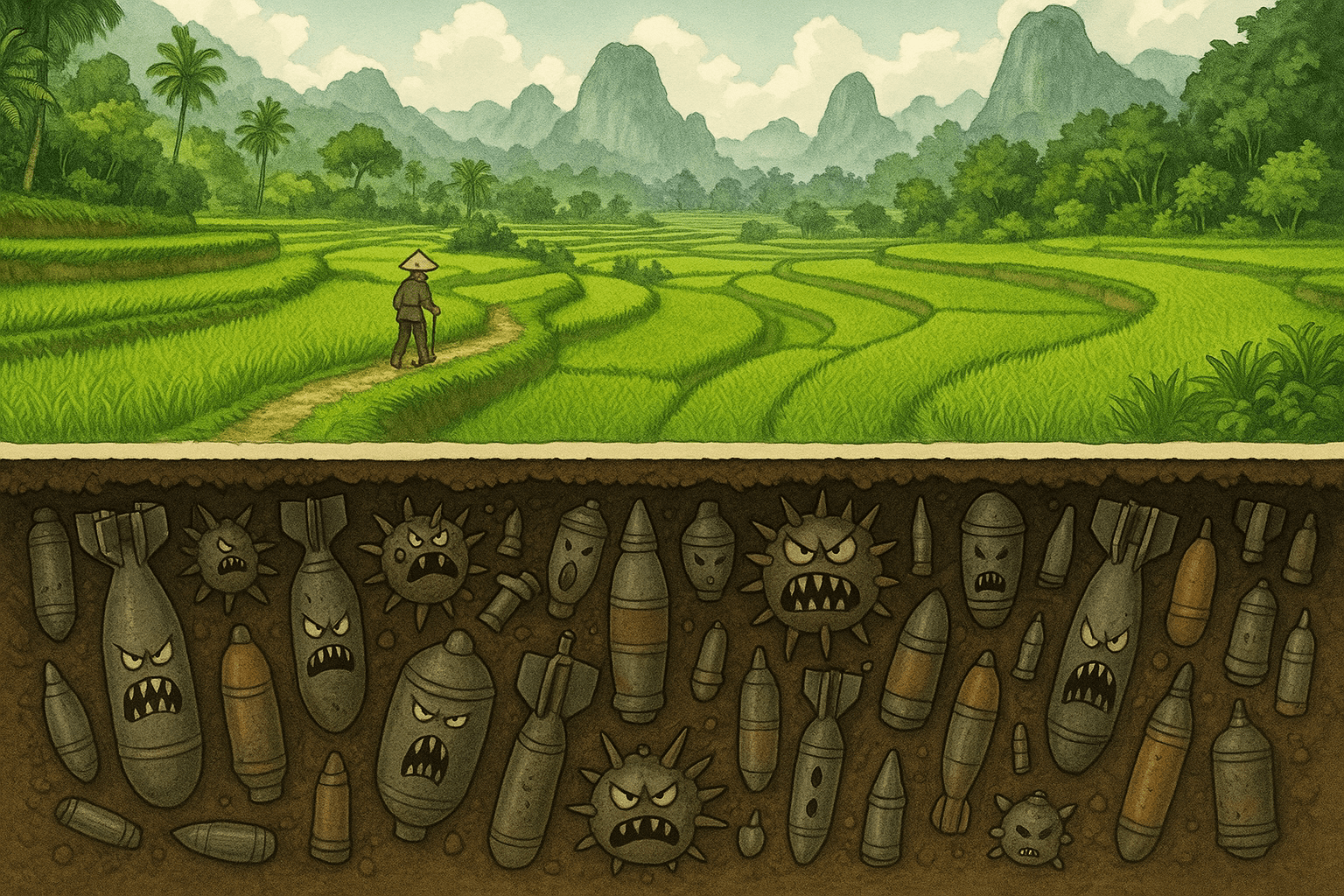

This contamination creates a devastating intersection of physical and human geography. The very land that people rely on for subsistence farming is the most dangerous. For a rural family, the choice is often between facing potential starvation or risking their lives to plant rice.

How UXO Reshapes Landscapes and Lives

The presence of unexploded ordnance fundamentally alters the relationship between people and their environment. It is a powerful agent of geographical change, imposing its own cruel logic on human activity.

The Crippling of Agriculture

In agrarian societies, UXO is a direct threat to food security. Farmers and their children are the most frequent victims. Fertile land is declared “Confirmed Hazardous Areas”, effectively removing it from productive use. This land denial forces communities to over-farm smaller, safer plots, leading to soil degradation and lower yields. Every act of cultivation—plowing, hoeing, digging for irrigation—becomes a life-or-death gamble.

Stifling Development

Progress is built on safe ground. The presence of UXO stalls or exponentially increases the cost of essential development projects. Before a new school, road, well, or power line can be built, the land must be painstakingly cleared. This diverts precious funds and delays progress for generations, trapping communities in a cycle of poverty that the conflict itself initiated. A region’s economic geography becomes frozen in time.

The Fabric of Daily Life

Living with UXO means living with constant, low-level fear. It also leads to a grim form of adaptation. In Laos, the casings of defused bombs are ubiquitous, repurposed as fence posts, planters, building supports, and even canoes. While a striking visual of resilience, it’s a constant reminder of the danger that still lurks unseen. Tragically, a shadow economy often emerges around scrap metal, where impoverished people risk their lives to find and dismantle ordnance for a pittance.

The Geographical Challenge of Clearance

Making the earth safe again is a slow, methodical, and geographically complex process. Organizations like the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) and The HALO Trust are on the front lines, but the terrain is their biggest adversary.

Clearance teams use a combination of historical records, satellite imagery, and community interviews to map suspected hazardous areas. Deminers with metal detectors then walk the land, meter by painful meter. In the rugged mountains of Laos or the dense jungles of Colombia, this work is slow and perilous. Steep slopes, metallic-rich soil that gives false positives, and dense vegetation all hinder progress. Modern tools like drones and advanced Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are helping to create more accurate maps, but the core work remains on the ground.

The legacy of a few years of war can take centuries to erase. The “iron harvest” in Belgium continues a full century after WWI ended. For Laos, experts estimate that at the current pace, it will take over 100 years to clear the most dangerous areas.

The geography of unexploded ordnance is a story of a war’s afterlife. It shows how conflict isn’t just a historical event, but a lingering physical presence that continues to claim victims, suppress economies, and shape the very contours of the land. It is a powerful, tragic reminder that the last act of a war is not a peace treaty, but the final, painstaking reclamation of the ground beneath our feet.