The Anatomy of a Water Tower

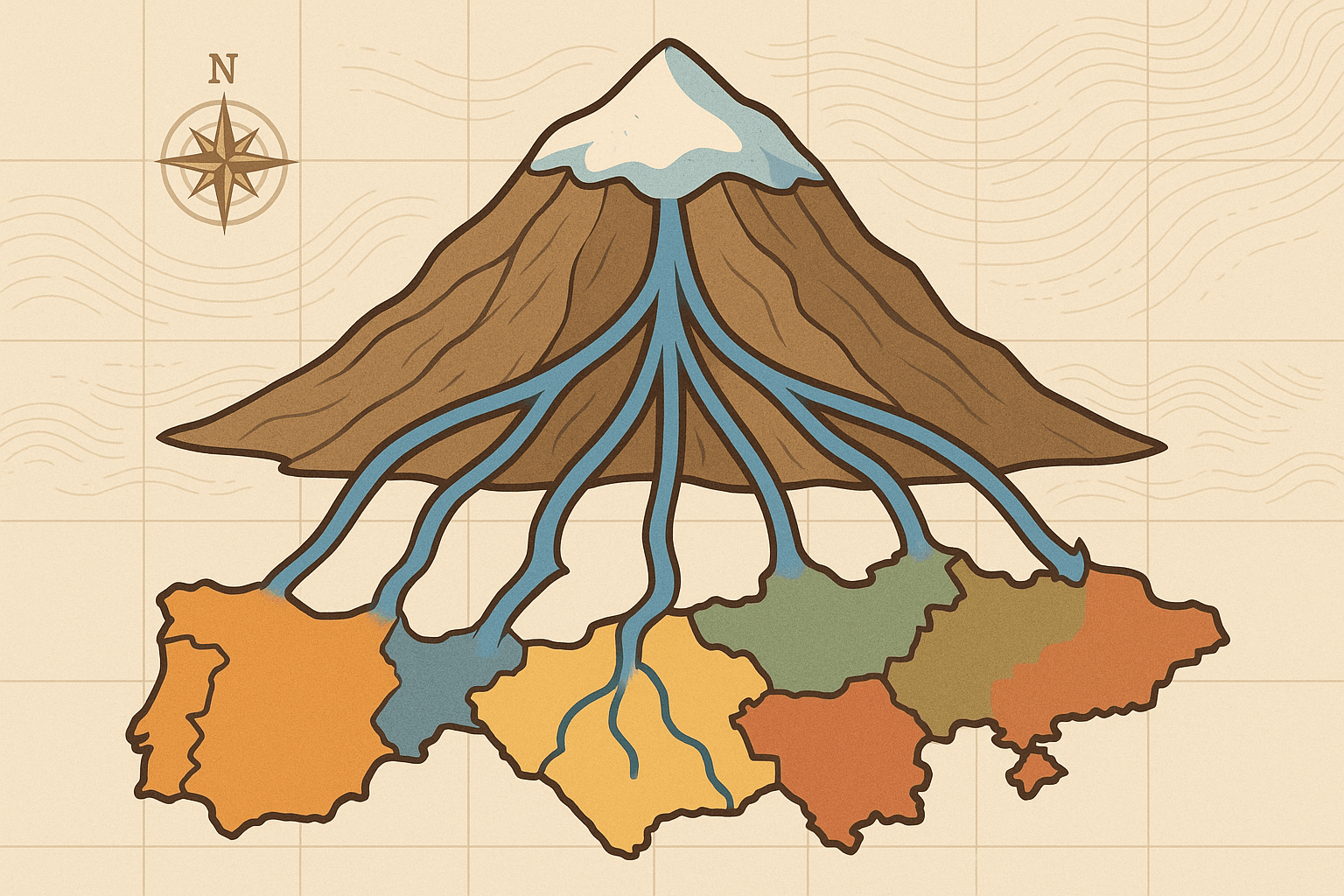

To understand the geopolitics, we first have to appreciate the physical geography. Mountain water towers aren’t simply large rocks that water runs off. They are intricate hydrological engines, working through a few key processes:

- Orographic Lift: As moisture-laden air masses are forced to rise over a mountain range, the air cools and condenses, causing precipitation. This is why the windward side of a mountain is typically far wetter than the leeward “rain shadow” side.

- The Cryosphere Reservoir: This precipitation often falls as snow, accumulating over winter and forming vast snowpacks and glaciers. This frozen water, known as the cryosphere, acts as a massive natural reservoir, storing water for months or even millennia.

- Gradual Release: Unlike a sudden downpour in the lowlands, this frozen reservoir releases its water gradually. The spring and summer melt provides a consistent, reliable flow into rivers precisely when downstream agricultural plains are at their driest. This natural regulation is a service of incalculable value.

When a single mountain range serves as the headwaters for rivers flowing into multiple countries, its geography becomes a map of potential conflict. The nation that controls the high-altitude source—the “faucet”—holds immense power over its downstream neighbors.

The “Third Pole”: Geopolitical Flashpoint in the Himalayas

Nowhere is this dynamic more pronounced than in Asia’s Hindu Kush-Himalayan (HKH) region. Spanning eight countries and holding the largest concentration of ice outside the polar regions, it has been dubbed the “Third Pole.” The glaciers and snowmelt of the HKH feed ten of Asia’s largest river systems, including the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Mekong, Yangtze, and Yellow Rivers. The lives and economies of over 1.9 billion people are tied to this single geographical feature.

Case Study: The Indus River

The Indus River originates on the Tibetan Plateau in China, flows west through Ladakh in India, and then turns south, becoming the absolute lifeline of Pakistan before emptying into the Arabian Sea. Pakistan, one of the world’s most water-scarce countries, relies on the Indus basin for over 90% of its food production. This geography creates a situation of profound vulnerability. Any dams or water diversion projects built by India upstream on the Indus and its tributaries are viewed in Islamabad as a potential existential threat. The 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, brokered by the World Bank, has largely prevented outright war by allocating different tributaries to each nation. However, it remains a fragile peace, constantly tested by political tensions and the growing threat of climate change, which is causing Himalayan glaciers to retreat at an alarming rate.

Case Study: China’s Upstream Dominance

China’s control of the Tibetan Plateau makes it the ultimate upstream power in Asia. It controls the headwaters of both the Brahmaputra and the Mekong, two rivers vital to its southern neighbors.

- The Brahmaputra: Known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet, this mighty river flows east before making a dramatic turn south into Arunachal Pradesh, India, and then into Bangladesh. China’s massive dam-building activities on the river, undertaken without consultation, have sparked deep anxiety in New Delhi and Dhaka. The fear is not just about reduced water flow, but also China’s ability to release or withhold water at will, potentially exacerbating floods or droughts downstream.

- The Mekong: Rising in Tibet, the Mekong winds its way through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The Mekong Delta in Vietnam is one of the world’s great rice bowls, entirely dependent on the river’s seasonal flow and the nutrient-rich sediment it carries. China’s cascade of upstream dams has been blamed for record-low water levels, disrupting fisheries in Cambodia’s Tonlé Sap lake and threatening the agricultural viability of the Vietnamese delta. China’s lack of transparency regarding dam operations turns a shared natural resource into a tool of geopolitical leverage.

Beyond Asia: Global Mountain Hotspots

While the Himalayas are the grandest example, the geopolitics of mountain water towers is a global phenomenon.

The Nile River: The story of the Nile is a classic upstream-downstream conflict. While often associated with Egypt, over 85% of its water originates as rainfall in the Ethiopian Highlands, feeding the Blue Nile. For millennia, Egypt and Sudan enjoyed historical dominance over the river’s flow. But Ethiopia’s construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) near the border with Sudan has completely upended this dynamic. Ethiopia sees the dam as essential for its development and electricity generation. Egypt, a desert nation utterly dependent on the Nile, views it as a direct threat to its water supply and national security. The dispute highlights how a single geographical feature—a highland plateau—can redefine regional power dynamics.

Central Asia’s Tian Shan Mountains: The Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, which once fed the Aral Sea, originate in the Tian Shan and Pamir mountains of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. These upstream nations are mountain-rich but energy-poor. They seek to build hydropower dams to generate electricity. However, the downstream nations—Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan—are agricultural powerhouses that rely on that same water for irrigation. This pits the upstream need for energy against the downstream need for water, creating a constant source of regional tension that is a direct legacy of Soviet-era borders drawn without regard for hydrological geography.

Navigating a Thirsty Future

The geography of mountain water towers is a geography of interdependence. While the potential for conflict is immense, it also creates a powerful incentive for cooperation. The path forward requires moving beyond zero-sum thinking.

Key to this is the establishment of robust, transparent, and adaptable transboundary water-sharing agreements. Unlike older treaties, new frameworks must account for the impacts of climate change and include all stakeholders, not just national governments. Crucially, they must mandate the sharing of real-time data on water flow, snowpack, and dam operations to build trust and allow for effective planning.

Ultimately, the mountains send us a clear message: water flows across the borders that we draw on maps. How we manage these shared high-altitude lifelines will determine the stability and prosperity of vast swathes of our planet for generations to come.