Mapping Russia’s Linguistic Tapestry

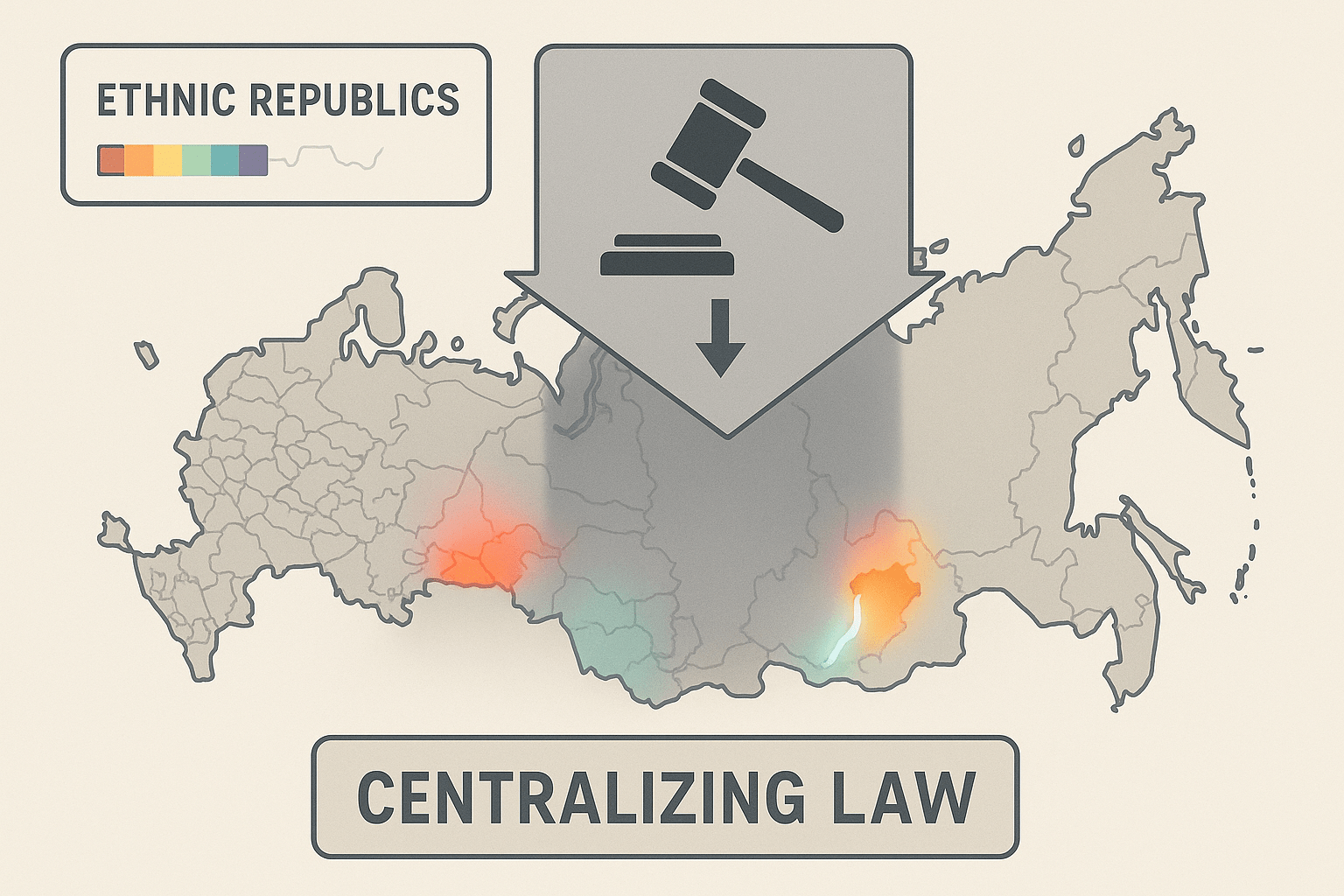

To understand the law’s impact, one must first appreciate the staggering human geography of Russia. Far from being a monolithic, ethnically Russian nation-state, the Russian Federation is a mosaic of a country, home to over 190 distinct ethnic groups. Encoded in its very structure are 22 “ethnic republics”, territories designated for a specific non-Russian ethnic group, which, at least on paper, hold special status and the right to their own state language alongside Russian.

These republics form a complex archipelago of cultural and linguistic diversity embedded within the larger Russian state. Let’s trace their geography:

- The Volga-Urals Region: In the heart of European Russia, republics like Tatarstan (capital: Kazan) and Bashkortostan (capital: Ufa) are home to Turkic-speaking Tatars and Bashkirs. This region is historically significant, economically powerful, and has long been a center of a moderate and distinct form of Islam.

- The North Caucasus: A mountainous, strategic, and often volatile strip of land between the Black and Caspian Seas. This is Russia’s most linguistically diverse area. Here, Chechnya (Grozny), Dagestan (Makhachkala), and Ingushetia (Magas) are home to dozens of unique Caucasian languages. For these cultures, forged in resistance to centuries of imperial expansion, language is inextricably linked to identity and survival.

- Siberia and the Far East: Across the vast, resource-rich taiga and tundra lie republics like Sakha (Yakutia), a territory larger than Argentina, where the Turkic Sakha language is spoken, and Buryatia, near Lake Baikal, a center of Russian Buddhism where the Mongolic Buryat language thrives.

For decades, the delicate balance of power between Moscow and these republics was maintained through a system where both Russian (the federal language) and the titular republican language were mandatory in schools. This system acknowledged the country’s diversity. The 2018 law shattered that balance.

The Law as a Geopolitical Lever

Officially, the 2018 legislation was framed as a move to “protect the rights of Russian speakers” and create a “unified educational space.” The reality, however, is a clear geopolitical strategy to achieve two of the Kremlin’s long-term goals: centralization of power and the promotion of a singular national identity.

Weakening Regional Power Centers

Language is the ultimate vehicle for culture, history, and a shared sense of self. It is the invisible infrastructure of a nation. By making the study of regional languages optional—knowing full well that the pressures of state exams and university admissions heavily favor Russian—the Kremlin is systematically dismantling one of the key pillars of republican autonomy. A generation of Tatars, Chechens, or Buryats who cannot fluently read, write, or think in their ancestral tongue is a generation less connected to their unique regional identity and more tethered to the center: Moscow.

This is a quiet but effective way to neutralize potential sources of dissent or separatism. The resource-rich republics of the Volga and the strategic territories of the Caucasus have historically been the most assertive in demanding autonomy. By eroding the linguistic foundation of their distinctiveness, Moscow makes them more governable and less likely to challenge federal authority.

Forging a “Russian World”

The law also serves a powerful ideological purpose. There is a crucial distinction in the Russian language between russkiy (ethnic Russian) and rossiyskiy (a citizen of the Russian Federation, regardless of ethnicity). For years, the Kremlin has been working to blur this line, promoting a national identity that is increasingly synonymous with ethnic Russian culture, the Russian language, and the Orthodox Church. This concept is often called the Russkiy Mir, or “Russian World.”

By mandating Russian and demoting other languages, the state is sending a clear message: to be a successful and fully integrated citizen of the Russian Federation (a rossiyskiy citizen), one must assimilate into the dominant russkiy culture. It is an assertion that the civic identity of the country is, at its core, an ethnic Russian one. This project of national consolidation is seen by the Kremlin as essential for projecting strength both domestically and abroad.

The View from the Republics: Resistance and Resignation

The reaction to the law was not uniform; it varied according to the unique geography and political situation of each republic.

The epicenter of resistance was Tatarstan. As one of the most populous and economically successful republics, Kazan mounted the strongest defense of its linguistic rights. Activists organized protests, and Tatarstan’s political leaders initially pushed back hard against Moscow’s pressure, citing the Russian constitution which grants republics the right to their own state language. For them, the law was a betrayal of the federalist principles that are supposed to hold the country together. Despite their efforts, they were ultimately forced to comply.

In the North Caucasus, the situation was more subdued, but no less tense. In places like Chechnya, where strongman leader Ramzan Kadyrov’s power is entirely dependent on his loyalty to Vladimir Putin, open defiance was impossible. Instead, regional leaders have tried to compensate by doubling down on promoting their language and culture through other means—festivals, public signage, and state-sponsored media—even as its role in the classroom diminishes. It is a tacit acknowledgement of Moscow’s power, coupled with a desperate attempt to keep their culture alive.

For activists across Russia, the long-term fear is “linguicide”—the gradual, state-engineered death of a language. When a language recedes from the public sphere and the classroom, it is forced to retreat into the private sphere of the home. Within a few generations, without formal instruction, its vocabulary shrinks, its grammar falters, and its utility as a living, breathing medium of communication fades.

The Redrawing of a Nation’s Soul

The 2018 language law is far more than a footnote in education policy. It is a deliberate and strategic act of geopolitical engineering. It uses the schoolhouse as a frontier for national consolidation, seeking to smooth over the complex linguistic and cultural contours of Russia into a more uniform, centralized, and Moscow-centric whole. The battle over whether a child in Dagestan or Yakutia learns Avar or Sakha is, in reality, a battle for the future political geography of Russia itself. It raises a fundamental question: can a state as vast and diverse as Russia forge a single national identity without erasing the many nations that exist within it?