A Riverine Nation’s Arteries

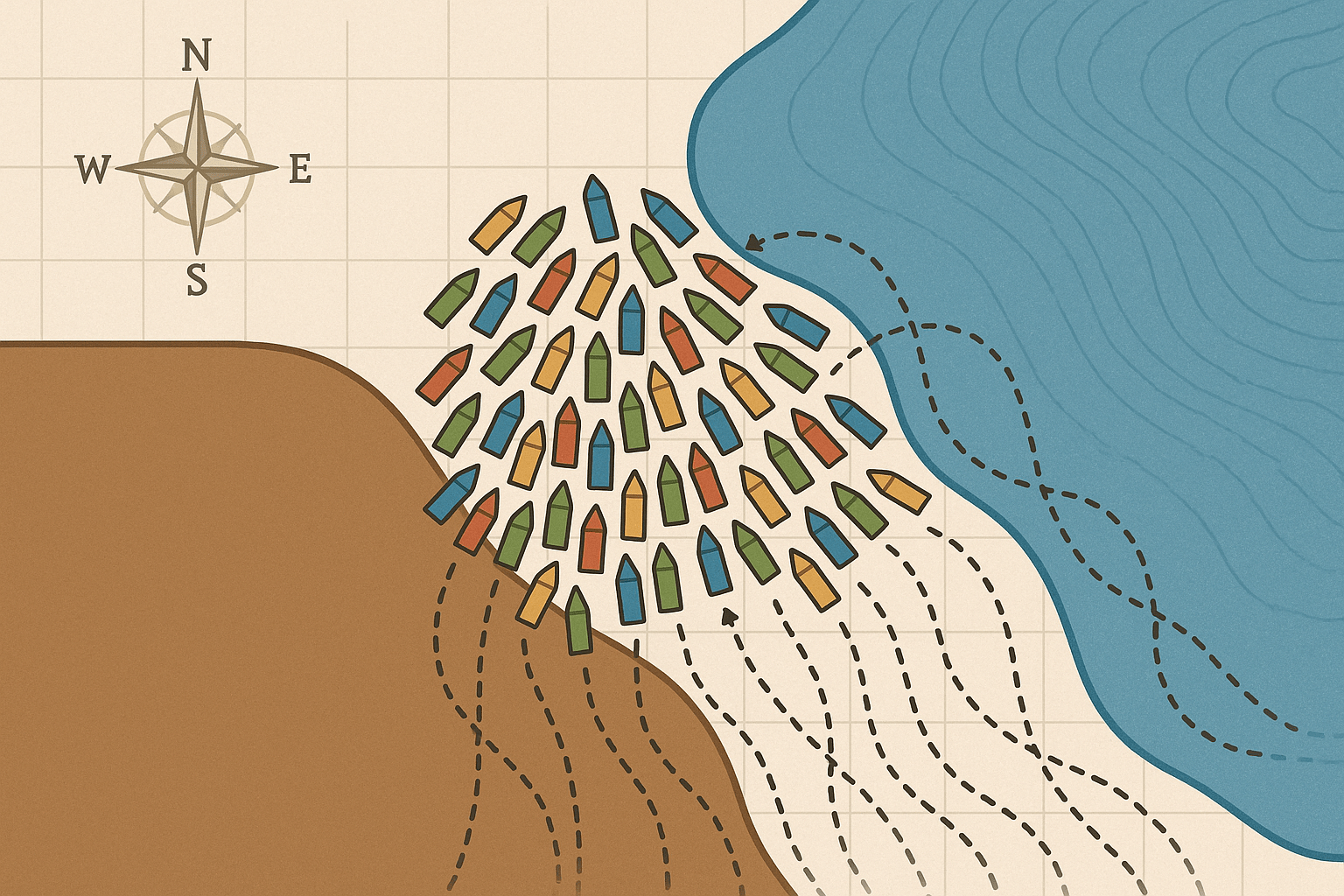

Understanding the ghat requires first understanding the map of Bangladesh. This is the world’s largest river delta, a latticework of over 700 rivers, tributaries, and distributaries that crisscross the landscape. The mighty Padma (the local name for the Ganges), the Meghna, and the Jamuna (Brahmaputra) carve the country into distinct regions, making land-based travel difficult, and in many cases, impossible. For centuries, these waterways have been the primary highways.

The ghats, therefore, are not an optional extra; they are a geographical necessity. They are the critical nodes that connect this fragmented landmass. They are where a farmer from a remote southern island brings his produce to the urban market, where a student from a village travels to a university in the capital, and where entire families migrate for work or return home for the Eid holidays. The ghat is the terrestrial anchor in a world dominated by water, the essential link in the nation’s logistical chain.

The Controlled Chaos: A Logistical Ballet

The daily operation of a major ghat like Sadarghat in Dhaka or the Paturia-Daulatdia crossing is a masterpiece of informal choreography—a logistical ballet on a grand scale. The star performers are the massive, multi-decker launches, towering structures of steel that can carry thousands of passengers and tons of cargo. These behemoths arrive with a great roar, maneuvering with surprising agility into impossibly tight spaces along the concrete embankments.

The moment a launch docks, the performance begins. Ropes as thick as a man’s arm are thrown and secured. Before the gangplank is even stable, a frantic exchange begins. A river of people flows off the vessel while another, equally determined river, flows on. Coolies, or porters, are the principal dancers in this scene. Often rail-thin but with immense strength, they navigate the surging crowds with precarious towers of goods balanced on their heads—sacks of rice, crates of chickens, furniture, even motorcycles—all for a few Taka per trip. Their movements are a testament to a lifetime of experience, weaving through the chaos with an instinctual grace.

Meanwhile, smaller wooden boats, or noukas, dart around the giants like pilot fish, ferrying passengers for shorter cross-river trips or bringing last-minute supplies directly to the sides of the larger launches. Everything is in constant motion, a seemingly anarchic system that, through unwritten rules and shared understanding, functions with remarkable efficiency.

The Informal Economy: A City Within a City

The ghat is much more than the sum of its boats and passengers. It is a sprawling, self-sustaining economic ecosystem that thrives on the constant flow of people. Step away from the immediate waterfront, and you are in the heart of a bustling marketplace, a micro-city powered entirely by the informal sector. The entire area is a maze of commerce, offering everything a traveler could possibly need:

- Food and Drink: Tiny tea stalls, known as tongs, are the social hubs, serving sweet, milky tea and gossip. Hawkers weave through the crowds selling jhalmuri (a spicy puffed rice snack), boiled eggs, and bananas. More permanent shacks offer full meals of rice and curry, catering to both hurried travelers and the people who work at the ghat.

- Goods and Services: You can find vendors selling newspapers, mobile phone chargers, cheap plastic toys, locks for luggage, and traditional lungis. There are barbers offering shaves on a wooden stool and money-changers handling small currency.

- Transport: A fleet of rickshaws, auto-rickshaws (CNGs), and buses wait at the ghat’s periphery, ready to complete the final leg of a traveler’s journey, forming the crucial link between the river and the road network.

This entire economy is symbiotic. The tea-seller depends on the coolie, who depends on the passenger, who depends on the launch. It is a fragile but resilient system that provides a livelihood for tens of thousands of people who might otherwise have none.

The Social Fabric and Human Geography

As a point of convergence, the ghat is a fascinating cross-section of Bangladeshi society. On any given launch, you will find a microcosm of the nation. Wealthier passengers book private, air-conditioned cabins, enjoying a comfortable and secluded journey. Meanwhile, the vast majority travels on the open decks, staking out a small space with a mat or a blanket for what is often an overnight trip. They share food, tell stories, and watch the river slide by, creating a temporary community on the water.

The ghat itself has its own distinct social hierarchy. At the top are the launch owners and powerful transport syndicates. Below them are the established shopkeepers and vendors with permanent stalls. Further down are the coolies, whose lives are defined by hard physical labor and precarious daily wages. At the very bottom are the most vulnerable: transient hawkers, beggars, and homeless children for whom the ghat is not a point of transit, but a permanent, unforgiving home.

Each face in the crowd represents a unique story of human geography—a story of migration, of commerce, of celebration, of desperation. The ghat is the stage where these countless personal dramas unfold, day after day.

To truly understand the geography of Bangladesh, you must look beyond the lines on a map. You must see the living, breathing networks that connect its people. The ghats are far more than just dots on the riverside; they are the loud, chaotic, and profoundly human heart of a nation shaped by water.