This trail is a story of human geography, carved by the currents of global trade and the coastlines of economic disparity. It’s a journey from the sanitized streets of New York, London, and Tokyo to the riverbanks, coastal towns, and sprawling dumps of Southeast Asia, West Africa, and South Asia. To understand our waste, we have to understand its geography.

The Great Conveyor Belt of Consumption

The global waste trade is built on a simple economic principle: for many wealthy nations, it is cheaper to export waste than to process it at home. High labor costs and stringent environmental regulations, like landfill taxes and emissions standards, make domestic recycling and disposal expensive. Conversely, developing nations often have lower labor costs, less restrictive regulations, and a workforce willing to perform the difficult, dangerous work of sorting and dismantling refuse for a small income.

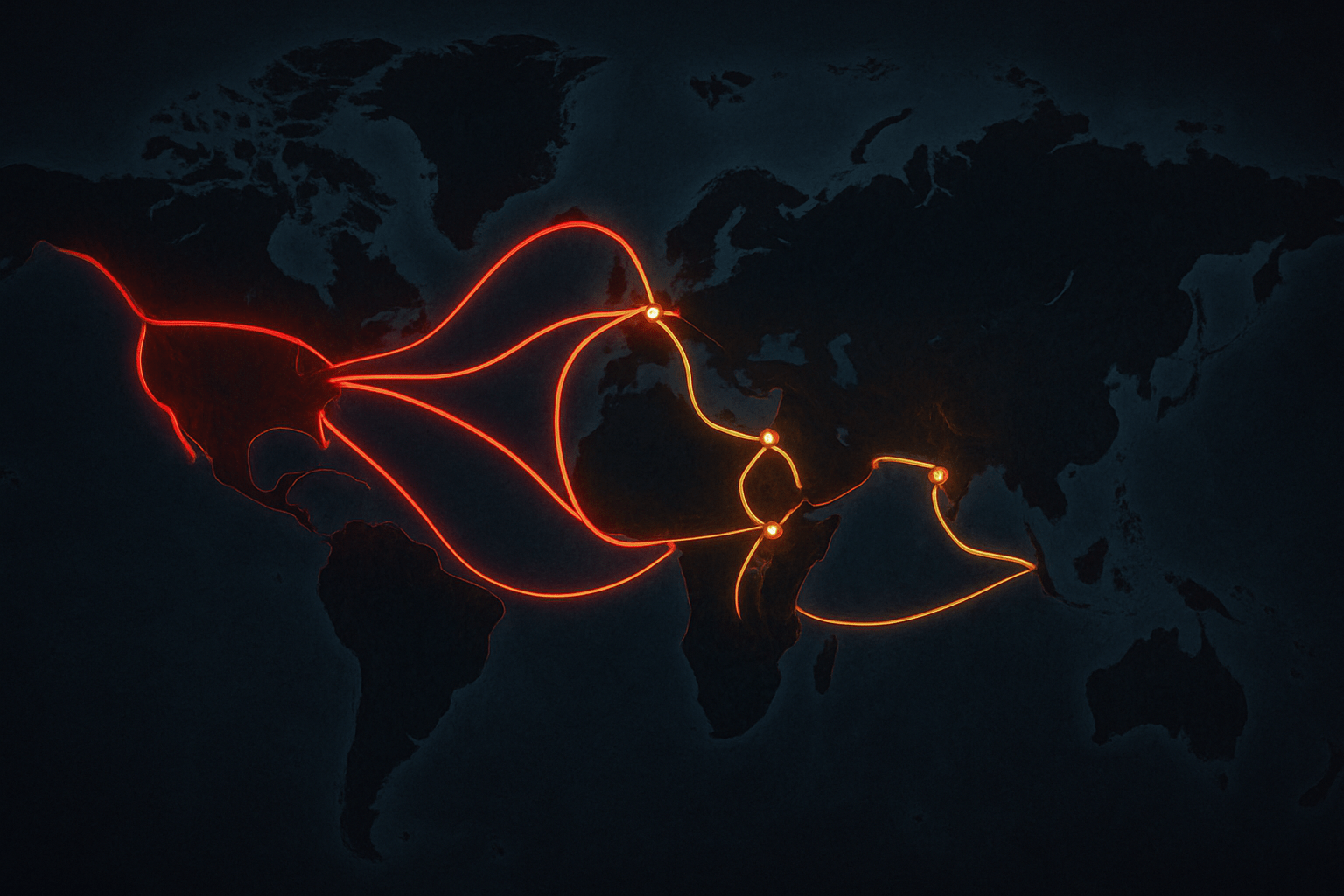

This creates a powerful economic conveyor belt. Bales of crushed plastic and shipping containers filled with discarded electronics are loaded onto cargo ships in the same ports that deliver consumer goods—places like the Port of Los Angeles or Rotterdam. These containers then travel across major shipping lanes, tracing the reverse path of our consumer products. The primary exporters are the world’s biggest consumers: the United States, the European Union, Japan, and Canada. For decades, the primary destination was China, which had an insatiable appetite for raw materials to fuel its manufacturing boom.

The Plastic Odyssey: A Post-China Scramble

For years, the geography of plastic waste was simple: it went to China. But in 2018, everything changed. China’s “National Sword” policy slammed the door shut, banning the import of most plastic scrap. This single act of policy created a seismic shift in the physical geography of global waste, triggering a desperate scramble for new destinations.

The plastic tide immediately diverted to Southeast Asia. Countries like Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia saw their plastic imports skyrocket. The geography of the problem became localized and acute:

- Malaysia: The town of Jenjarom, near Port Klang (one of Southeast Asia’s busiest ports), became an international symbol of the crisis. Illegal recycling factories sprang up, blanketing the area in toxic fumes from burning unsorted plastic and leaving behind mountains of non-recyclable residue.

- Indonesia: Along the Brantas River, villages became dumping grounds. Imported plastic scrap, often hidden within bales of waste paper, contained low-grade material that was worthless for recycling. It ended up being burned as fuel in local tofu factories or dumped directly on the riverbanks, choking the waterway that provides drinking water for millions.

- Vietnam: The port city of Haiphong was inundated with containers of plastic scrap, overwhelming customs and port capacity. The waste spilled into the surrounding countryside, polluting agricultural land and coastal ecosystems in the Gulf of Tonkin.

This rerouting of the plastic trail highlights how a geopolitical decision in one country can have profound physical and human geography impacts thousands of miles away.

E-Waste’s Toxic Geography: The Digital Dumps of West Africa

The journey of our obsolete electronics—laptops, phones, televisions—traces another, even more toxic, map. A significant portion of this e-waste ends up in West Africa and parts of Asia, often illegally exported under the guise of “donations” or “used goods.”

The most infamous destination is Agbogbloshie in Accra, Ghana. Once a coastal wetland on the banks of the Korle Lagoon, it is now one of the world’s largest digital graveyards. Here, the human geography is one of informal, perilous labor. Young men and boys, many of them internal migrants from poorer northern Ghana, smash cathode-ray tubes to get to the copper yoke, releasing toxic lead dust. They burn insulated cables in open fires to melt away the plastic and isolate the valuable copper, releasing a cocktail of carcinogens like dioxins and furans into the air. The physical geography is a scarred landscape of black soot, shattered glass, and plastic casings, where toxic runoff from heavy metals like lead, cadmium, and mercury flows directly into the nearby Odaw River and the lagoon, poisoning the water and the fish that local communities depend on.

Ghost Ships and Scrapyards of South Asia

It’s not just consumer products that travel. The largest objects we manufacture—ships—also have a final destination. The shipbreaking industry is concentrated on the tidal flats of South Asia, a location determined by a unique physical geography.

The beaches of Alang, India, on the Gulf of Khambhat, and Chittagong, Bangladesh, on the Bay of Bengal, have some of the highest tidal ranges in the world. This natural phenomenon allows massive, end-of-life tankers and container ships to be driven at full speed onto the beach during high tide. When the tide recedes, the ship is left stranded on the mudflats, ready to be dismantled by tens of thousands of workers.

The work is grueling and extremely dangerous. Workers cut apart the steel hulls with blowtorches, often without protective gear. They face risks from falling steel plates, explosions, and exposure to asbestos, PCBs, and heavy metal-laden paints. The environmental cost is immense, as residual oil, bilge water, and toxic materials seep directly into the coastal soil and marine ecosystem, devastating local fisheries and mangrove forests.

Closing the Loop, Shrinking the Map

The global garbage trail is not an inevitability. In recent years, the geography has begun to shift once more. Countries like Malaysia and the Philippines have started to physically ship containers of illegal waste back to their origin countries, a powerful act of geopolitical pushback against what many now call “waste colonialism.” International agreements like the Basel Convention are being strengthened to prevent wealthy nations from dumping hazardous waste on poorer ones.

Ultimately, the solution to this sprawling, toxic geography is not to find a new, more remote “away.” It’s to shrink the map entirely. This means closing the loop through a true circular economy, where products are designed for durability and recyclability. It means investing in advanced domestic recycling infrastructure and enforcing producer responsibility. And for us, as individuals, it means understanding that every item we discard has a potential destination, a physical place on the map where people and ecosystems bear the true cost of our consumption.