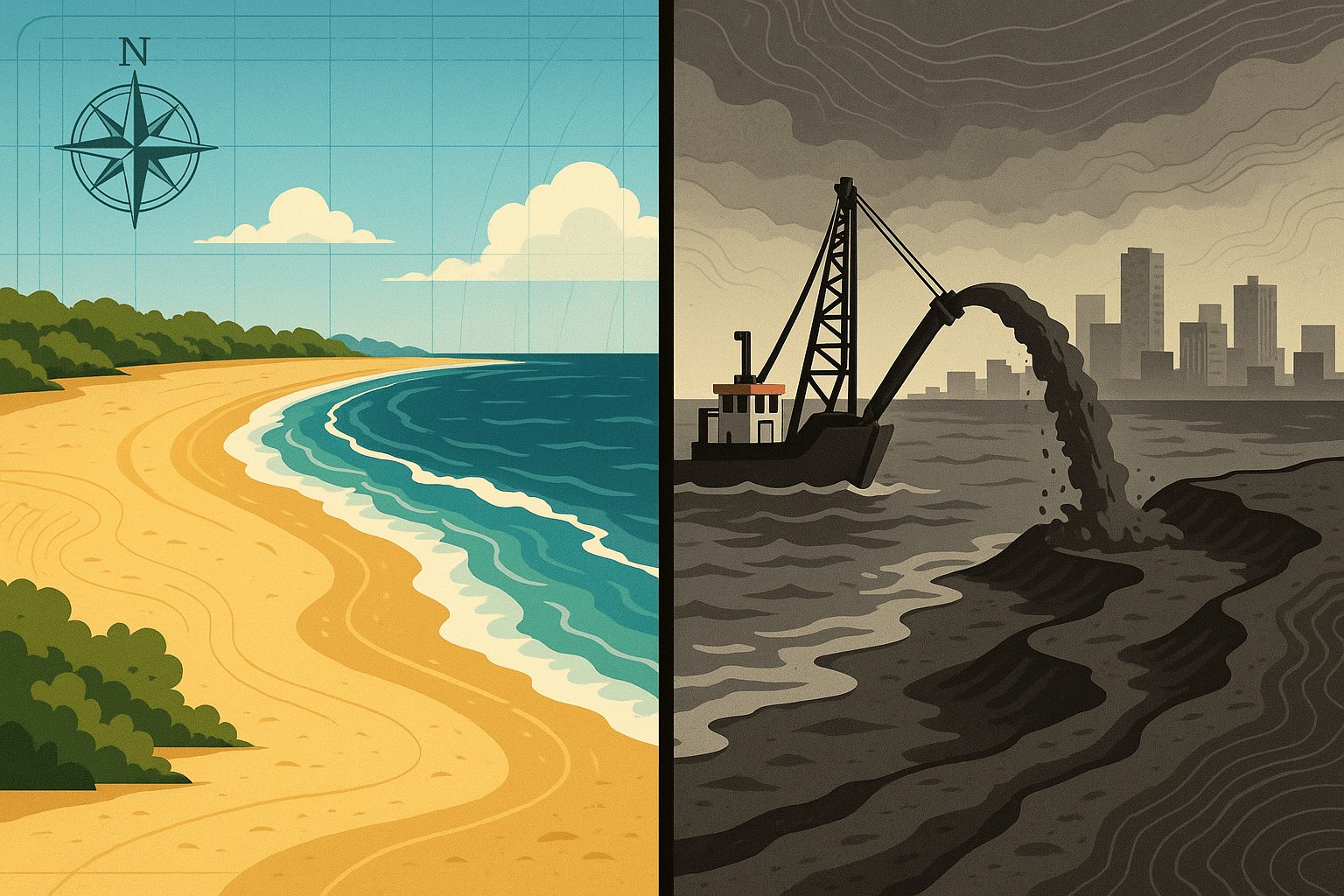

Picture a vast desert, dunes of fine, golden powder stretching to the horizon. Now, picture a sandy beach, waves lapping at an endless shore. It seems absurd to suggest we’re running out of sand. It’s the very symbol of abundance, of infinity. Yet, this perception is dangerously wrong. The world is facing a global sand crisis, a hidden shortage of a resource so fundamental to our civilization that its scarcity is redrawing maps, threatening ecosystems, and fueling a violent, shadowy economy.

The paradox lies in the type of sand we use. The wind-polished, rounded grains of desert sand are too smooth to bind together effectively in concrete. The sand we crave is the angular, gritty kind found in riverbeds, lakes, and on coastlines. And we crave it in staggering quantities. Sand is the primary ingredient in concrete, glass, and even the silicon chips in your phone. After water, it is the most consumed natural resource on the planet. Our modern world—our gleaming cities, sprawling infrastructure, and towering skyscrapers—is quite literally built on sand.

The Unquenchable Thirst of Urbanization

The engine driving this crisis is humanity’s relentless march toward urbanization. Every road paved, every dam built, and every high-rise erected requires colossal amounts of concrete. And for every ton of cement, the construction industry needs six to seven tons of sand and gravel.

Nowhere is this demand more apparent than in Asia. In just three years, from 2011 to 2013, China used more cement (and therefore, more sand) than the United States did in the entire 20th century. This insatiable appetite has led to the wholesale dredging of rivers and lakes. China’s Poyang Lake, its largest freshwater lake, has been so heavily mined for sand that its water levels have dropped dramatically, threatening the wetlands that are a critical stopover for migratory birds like the Siberian crane.

This story is repeated across the developing world. From the megaprojects in India to the rapid expansion of cities across Africa, the demand for sand is exploding, placing unprecedented pressure on fragile aquatic ecosystems.

Erasing the Map: The Environmental Toll

The consequences of this relentless extraction are a case study in devastating, large-scale environmental change. From a physical geography perspective, we are actively dismantling landscapes one bucket at a time.

- Sinking Deltas: Rivers naturally carry sediment downstream, replenishing deltas and coastlines. When we dredge sand from a riverbed, we starve the delta of this life-giving sediment. The Mekong Delta in Vietnam, a rice bowl for Southeast Asia, is sinking and shrinking. Sand mining on the Mekong River has become so intense that the delta is no longer being replenished, leaving it vulnerable to rising sea levels and saltwater intrusion that poisons rice paddies.

- Vanishing Coastlines and Islands: Sand mining from beaches and near-shore seabeds removes a coastline’s natural defense against storm surges and erosion. In Morocco, entire beaches have been stripped bare by illegal miners, leaving coastal towns exposed to the power of the Atlantic. Even more dramatically, in Indonesia, at least two dozen small islands are reported to have disappeared since 2005, submerged due to a combination of sea-level rise and rampant, often illegal, sand mining for export.

- Destroying Aquatic Habitats: The process of dredging, known as “in-stream mining”, churns up the riverbed, destroying fish spawning grounds, killing bottom-dwelling organisms, and clouding the water, which blocks sunlight from reaching aquatic plants. It fundamentally alters the river’s hydrology, leading to collapsing riverbanks and changing water flows.

Sand Wars and Geopolitical Tensions

Where there is a scarce, valuable resource, geopolitics and conflict are never far behind. Sand is no exception. It has become a strategic commodity, a source of tension between nations.

The city-state of Singapore is a prime example. As one of the world’s most densely populated nations, it has relied on land reclamation to expand its territory by over 20% since its independence. This expansion was built almost entirely on imported sand. For years, Singapore was the world’s largest sand importer, sourcing it from its neighbors like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Cambodia. This led to immense environmental damage in those countries and, eventually, diplomatic fallout. One by one, these nations banned sand exports to Singapore, citing ecological devastation and national security, creating a new front of geopolitical friction.

Further north, China has used sand as a tool of raw power projection, dredging massive quantities from the seabed to build artificial islands in the contested South China Sea, turning submerged reefs into military outposts complete with runways and harbors.

The Shadowy World of “Sand Mafias”

The immense value of sand, combined with often-poor regulation, has created a fertile ground for organized crime. In countries like India, the “sand mafias” are a powerful and violent force. These criminal syndicates illegally dredge sand from rivers and beaches, flouting environmental laws and terrorizing local communities.

Their operations are brutal and effective. They bribe officials, intimidate locals, and have been responsible for the deaths of hundreds of people, including journalists, activists, and police officers who have tried to expose or stop their activities. In India’s Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu states, riverbeds are scarred by illicit mining, a testament to the power of these gangs and the deadly consequences of our global demand.

Building a More Sustainable Future

The sand crisis is not insurmountable, but it requires a radical shift in how we think about and manage this resource. The solutions are complex and must be implemented on a global scale.

- Regulation and Governance: The sand trade is largely ungoverned at the international level. We need better monitoring, regulation, and enforcement to curb illegal mining and promote sustainable extraction practices.

- Recycling and Alternatives: We must move towards a circular economy. Recycled concrete and demolition waste can be crushed and reused as an aggregate, reducing the need for virgin sand. Other alternatives, like crushed rock, recycled glass, and even specially treated desert sand, are being explored.

- Smarter Design: Architects and engineers can play a role by designing buildings and infrastructure that use less concrete and are more resource-efficient.

The story of sand is a microcosm of the Anthropocene. It’s a tale of how a seemingly limitless resource can become scarce through unchecked consumption, and how its absence can unravel ecosystems, economies, and communities. The ground beneath our feet is literally shifting. We must recognize the true value of every grain before our concrete world is built on a foundation of sand that has simply washed away.