****

Ever wonder why you’ll drive past a small, local coffee shop to get to a giant Starbucks on the other side of town? Or why New York City, a global hub, has a stronger economic connection with London than with, say, Lima, Peru, even though Lima is significantly closer?

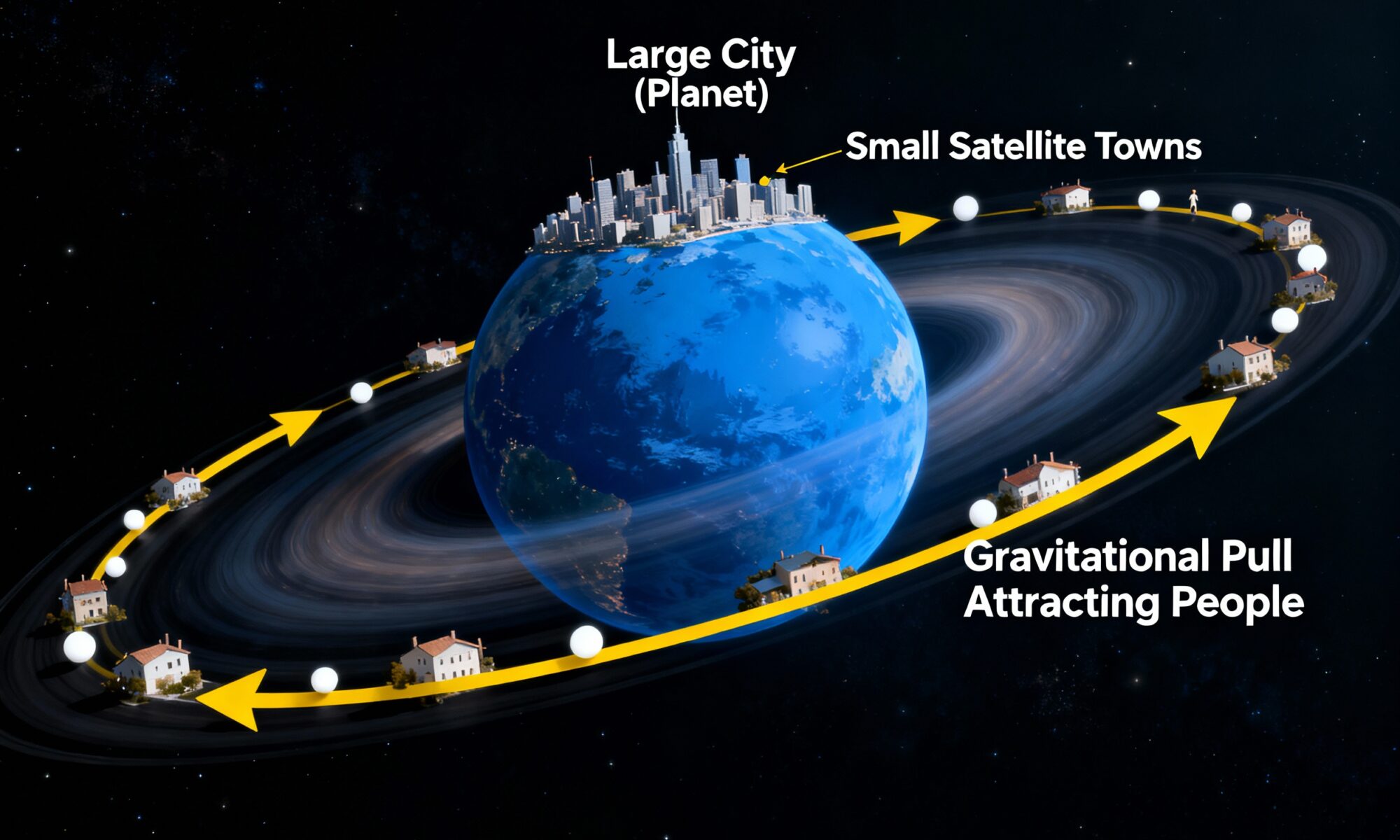

The answer to these seemingly unrelated questions lies in one of human geography’s most powerful and, frankly, weirdly accurate concepts: the Gravity Model. And no, it doesn’t involve calculating the gravitational pull of planets. But the logic is strikingly similar.

So, What Is the Gravity Model Anyway?

If you remember anything from high school physics, you might recall Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation, which states that the gravitational force between two objects is proportional to their mass and inversely proportional to the distance between them. Bigger objects have a stronger pull, and that pull weakens with distance.

The Gravity Model in geography hijacks this exact idea and applies it to people, cities, and countries. In simple terms, it predicts that the level of interaction between two places is a function of their size and their distance from each other.

Let’s break down the two key components:

- “Mass” (Size): In geography, “mass” isn’t about weight. It’s a measure of significance or attraction. For cities, this is usually population. For countries, it could be GDP. For a shopping center, it might be the number of stores or total square footage. The bigger the “mass”, the stronger its “gravitational pull.” A massive city like Tokyo or a huge economy like the United States exerts a major pull on everything from migrants to investment capital.

- Distance: This is the friction, the barrier to interaction. The further two places are apart, the weaker their connection will likely be. This core geographic principle is known as distance decay—the effect of distance on cultural or spatial interactions. As distance increases, the interaction decreases.

The model’s magic is in how these two forces play off each other. A place with a huge “mass” can overcome the friction of distance, while even a short distance can be a significant barrier for places with very small “mass.”

The Gravity Model in Your Daily Life

You don’t need to be a geographer or an economist to see this model in action. You live it every day. The Gravity Model helps explain the invisible logic behind many of your own choices.

Where You Shop

Think about your shopping habits. For a quick item like a gallon of milk, you’ll probably go to the closest convenience store. The “mass” of your need is small, so the friction of distance wins out—you’re not going to drive 20 minutes for one item.

But what if you need a new outfit, new electronics, and want to grab dinner? You’re more likely to drive past several smaller plazas to get to the large regional mall. The mall’s massive “pull” (its huge variety of stores, a food court, a movie theater) is strong enough to overcome the greater distance. The mall’s mass outweighs the friction of distance.

Your Favorite Sports Team

Why are there so many Boston Red Sox fans in New England but so few in Washington state? The answer is the “mass” of Boston and its proximity to the rest of the region. The team’s pull is strongest on those who are closest.

However, some teams, like the Los Angeles Lakers or Manchester United, have a massive global following. Their historic success and brand recognition give them such an enormous “mass” that their pull extends across continents, overcoming the immense friction of distance.

Scaling Up: Cities, Countries, and Global Connections

The same principles that dictate your trip to the mall also shape global patterns of migration, trade, and communication.

Migration Patterns

The Gravity Model is a fantastic predictor of migration flows. A person from a small town in rural Mexico is statistically far more likely to migrate to a large, nearby city like Los Angeles or Houston than to a smaller, more distant city like Charlotte, North Carolina. The massive “mass” (job opportunities, existing communities) of LA and Houston, combined with their relative proximity, creates a powerful gravitational pull.

This explains why major cities tend to draw migrants from their surrounding regions and from other large cities they are well-connected to.

International Trade

Look at a map of global trade, and the Gravity Model will stare right back at you. The United States’ largest trading partners are, unsurprisingly, Canada and Mexico. Why? They both have large economies (high “mass”) and they share a border with the US (very low “distance”).

The model also explains why the US trades more with Germany (a massive economy far away) than with Bolivia (a smaller economy much closer). Germany’s economic “mass” is so enormous that it overcomes the distance, creating a stronger trade relationship.

It’s a Model, Not an Infallible Law

While the Gravity Model is incredibly useful, it’s a simplification of a complex world. It gives us the general rule, but there are always exceptions and other factors that can bend, break, or modify the “laws of gravity.”

- Technology and Time-Space Compression: The internet, cheap air travel, and container shipping have effectively “shrunk” the world. This phenomenon, called time-space compression, reduces the friction of distance. It’s easier and cheaper to interact with someone on the other side of the globe today than it was 50 years ago, which weakens the “distance” variable in the model.

- Political Borders and Tariffs: A national border can act like a wall, creating far more friction than distance alone would suggest. The amount of trade between Seattle, USA, and Vancouver, Canada—two large, proximate cities—is significantly less than what the model would predict if that international border didn’t exist.

- Cultural and Linguistic Ties: Humans aren’t just calculating economic beings. Shared language, history, and culture create powerful bonds that defy simple distance calculations. For example, the strong relationship between the United Kingdom and Australia persists despite the immense distance, a legacy of their shared colonial history and language.

So, the next time you’re stuck in traffic on the way to a major airport, a bustling downtown, or a packed outlet mall, take a moment. You’re not just in traffic; you’re feeling the pull. You’re part of a massive, invisible web of connections, all governed by the strangely powerful logic of the Gravity Model.

**