A Line of Tax and Thorns

To understand the Hedge, we must first understand the British obsession with salt in 19th-century India. Salt was not a luxury; it was an essential dietary supplement for both humans and livestock, crucial for survival in a hot climate. The British East India Company, and later the British Raj, saw this necessity as a prime opportunity for revenue. They imposed a heavy tax on salt, which at times could increase its price by over 1,000 percent.

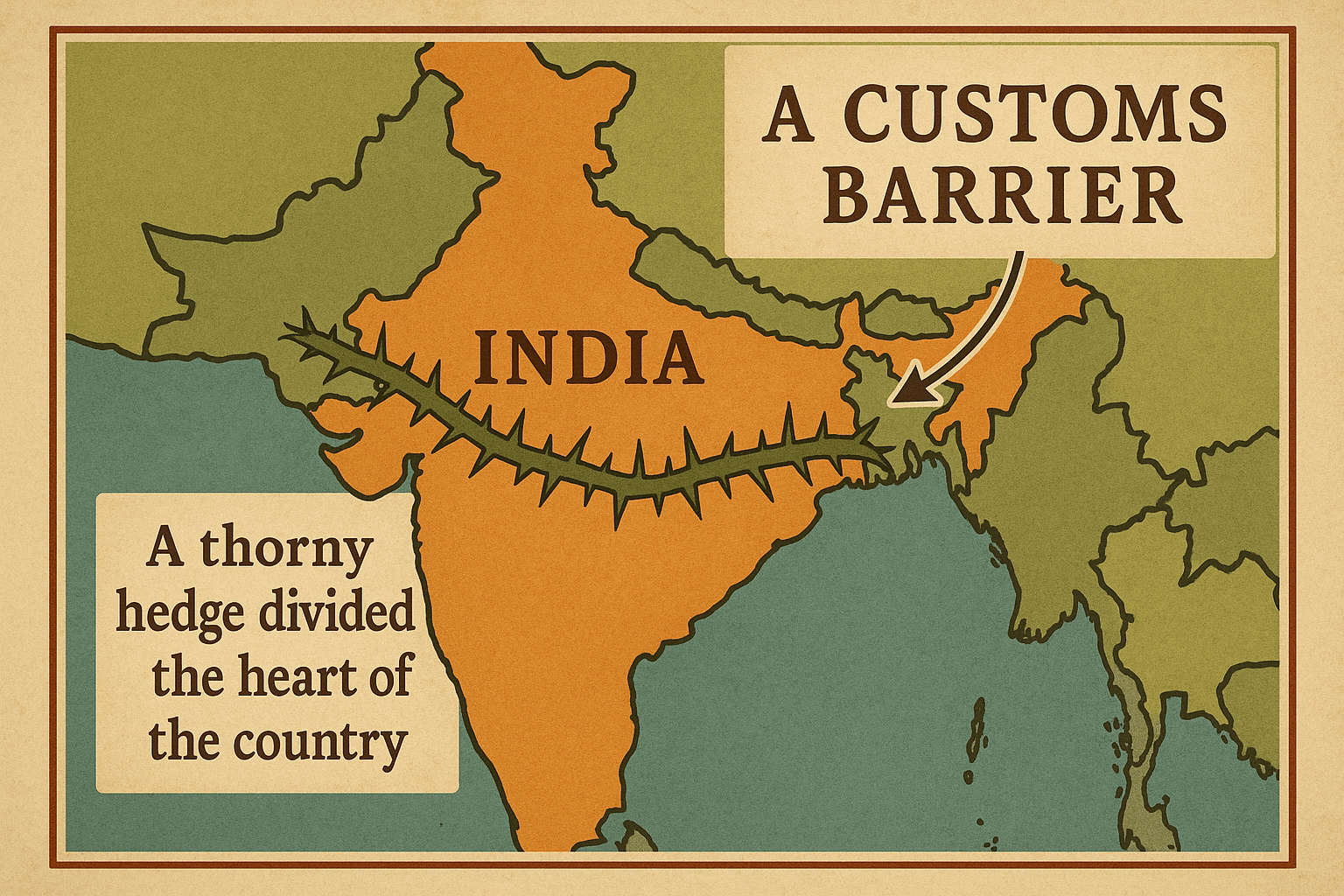

The geography of the subcontinent, however, made enforcement a nightmare. The western part of India, particularly the regions of Rajputana (modern Rajasthan) and the Rann of Kutch, was rich in natural salt from vast salt lakes and pans. In contrast, the eastern territories, including the populous Bengal Presidency, had few local sources. To prevent cheap, untaxed salt from the west from flooding eastern markets, the British established the Inland Customs Line in the 1840s.

Initially, this “line” was just a chain of customs posts along major roads and trade routes. But it was porous and easily bypassed. Smugglers, driven by desperation and profit, could simply trek through the countryside. The British response, championed by Customs Commissioner A. O. Hume, was audacious: they decided to create a physical barrier so immense and impenetrable that no one could cross it undetected. They decided to grow a hedge.

Charting a Botanical Fortress Across a Continent

At its greatest extent in the 1870s, the Great Hedge stretched approximately 2,500 miles (over 4,000 km), arguably longer than the Great Wall of China. Its path was a massive geographical undertaking, cutting across a vast swath of the Indian subcontinent.

- It began in the north, in the Punjab province at the foothills of the Himalayas, near modern-day Pakistan.

- From there, it ran south, shadowing the path of the Yamuna and Ganges rivers. It passed west of major cities like Delhi and Agra, the latter city being the headquarters of the Customs Line.

- It then veered southeast, traversing the vast, flat Gangetic plains of what is now Uttar Pradesh.

- The Hedge continued across the rugged, hilly terrain of Central India, through states we now know as Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.

- Finally, its southern end terminated in the Mahanadi River delta in the princely state of Orissa (now Odisha), near the Bay of Bengal.

This living wall traversed an incredible diversity of physical geography. It crossed sun-baked plains, navigated ravines and hills, and cut through dense forests. Its maintenance required an army of nearly 14,000 men—patrols, officers, and gardeners—stationed at customs posts every mile. The hedge was not just a line on a map; it was a living, breathing, and heavily policed border that divided the subcontinent in two.

The Anatomy of the Hedge

What did this botanical fortress look like? It was no simple garden hedge. The goal was to create a barrier that was, in the words of one official, “perfectly impassable to man or beast.” To achieve this, a carefully selected mix of hardy, thorny, and fast-growing native plants was used. The primary components were:

- Indian Plum (Ziziphus jujuba): A dense, thorny shrub that formed a strong base.

- Babool (Vachellia nilotica): A formidable acacia tree armed with long, sharp thorns.

- Prickly Pear (Opuntia): A cactus that could thrive in the driest sections of the line.

- Karonda (Carissa carandas): A tough shrub with robust thorns.

- Thorny varieties of Bamboo.

These were planted in a dense row, often reinforced with stone walls or earth embankments. Over time, the plants grew into each other, creating a tangled, interwoven mass of branches and thorns. In many places, the hedge was maintained to be 10 to 14 feet tall and up to 12 feet thick, creating a green wall that was far more difficult and painful to breach than a simple stone structure.

The End of the Line

For all its monumental scale, the Great Hedge was a monstrously inefficient and brutal system. It was hugely expensive to maintain, and it inflicted immense hardship on the poorest Indians, who were forced to pay exorbitant prices for a basic necessity or risk a dangerous smuggling journey. The human cost was immense.

By the late 1870s, even the British administration began to recognize its folly. A new strategy, spearheaded by the finance minister Sir John Strachey, was deemed far more efficient. Instead of policing a 2,500-mile-long border, the British consolidated their control over the major salt sources themselves, particularly the Sambhar Salt Lake in Rajasthan. By taxing the salt at its point of production, they could control the supply and render the entire Inland Customs Line obsolete.

In 1879, the line was officially abandoned. The army of customs officers was disbanded, and the Great Hedge was left to its fate. The end came swiftly. Without constant maintenance, nature began to reclaim it. Locals, for whom the hedge had been a symbol of oppression, quickly dismantled it for firewood and cleared the land for agriculture. Within a few decades, the most extensive customs barrier the world has ever seen simply vanished.

A Ghost on the Landscape

The story of the Great Hedge was so completely forgotten that for over a century, it was little more than a historical footnote in obscure colonial records. It was only in the 1990s that a retired British official, Roy Moxham, stumbled upon mentions of it and, through tenacious research and travel, pieced together its incredible story and traced its ghost-like path.

Today, almost nothing of the Great Hedge remains. There are a few disputed stretches of old earth-works or stubborn shrubs in remote parts of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh that might be its last vestiges. But the wall itself is gone, melted back into the very geography it was designed to control. It stands as a powerful and peculiar monument to the extremes of colonial rule—a reminder of how political power and economic policy can physically reshape a continent, and how even the most colossal human endeavors can be swallowed by the land and lost to memory.