This line, a scar etched across the landscape of an entire nation, is one of modern geography’s most peculiar and poignant features. It is more than just a political demarcation; it’s a physical barrier, a UN-controlled buffer zone, and an eerie time capsule, preserving the tumultuous events of the 1970s in brick and dust.

Drawn in Green: The Birth of a Border

The name “Green Line” sounds almost pastoral, but its origins are purely pragmatic. It was born from crisis. In December 1963, as intercommunal violence erupted between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots in Nicosia, the commander of the British peacekeeping forces, Major-General Peter Young, took a map of the city. With a green chinagraph pencil, he drew a line to separate the warring communities, establishing a ceasefire zone. That hasty line on a map would become a defining feature of the island’s geography.

The line was solidified and dramatically expanded following the events of 1974, which saw a Greek-led coup followed by a Turkish invasion. The island was split in two, and the Green Line evolved into the UN Buffer Zone in Cyprus (UNFICYP). This zone stretches approximately 180 kilometers (112 miles) from the island’s west coast near Kato Pyrgos to the east coast south of Famagusta. Its width varies dramatically, from several kilometers in rural areas to just a few meters in the dense urban maze of old Nicosia.

Nicosia’s Divided Heart: A Unique Urban Geography

Nowhere is the geographical impact of the Green Line more visceral than in Nicosia (known as Lefkoşa in the north). The city’s historic, star-fort-shaped Venetian walls, designed centuries ago to unify and protect, now encircle a divided core.

To walk the streets near the line is a lesson in urban geography interrupted:

- Dead-End Streets: Roads that once flowed with traffic and people now terminate abruptly at oil drums, sandbags, and concrete walls. A simple turn can take you from a lively café district to a silent, UN-patrolled frontier.

- Architectural Scars: Buildings within and along the edge of the zone are pockmarked with bullet holes, their facades crumbling. They stand as silent witnesses to the fighting that raged here nearly half a century ago.

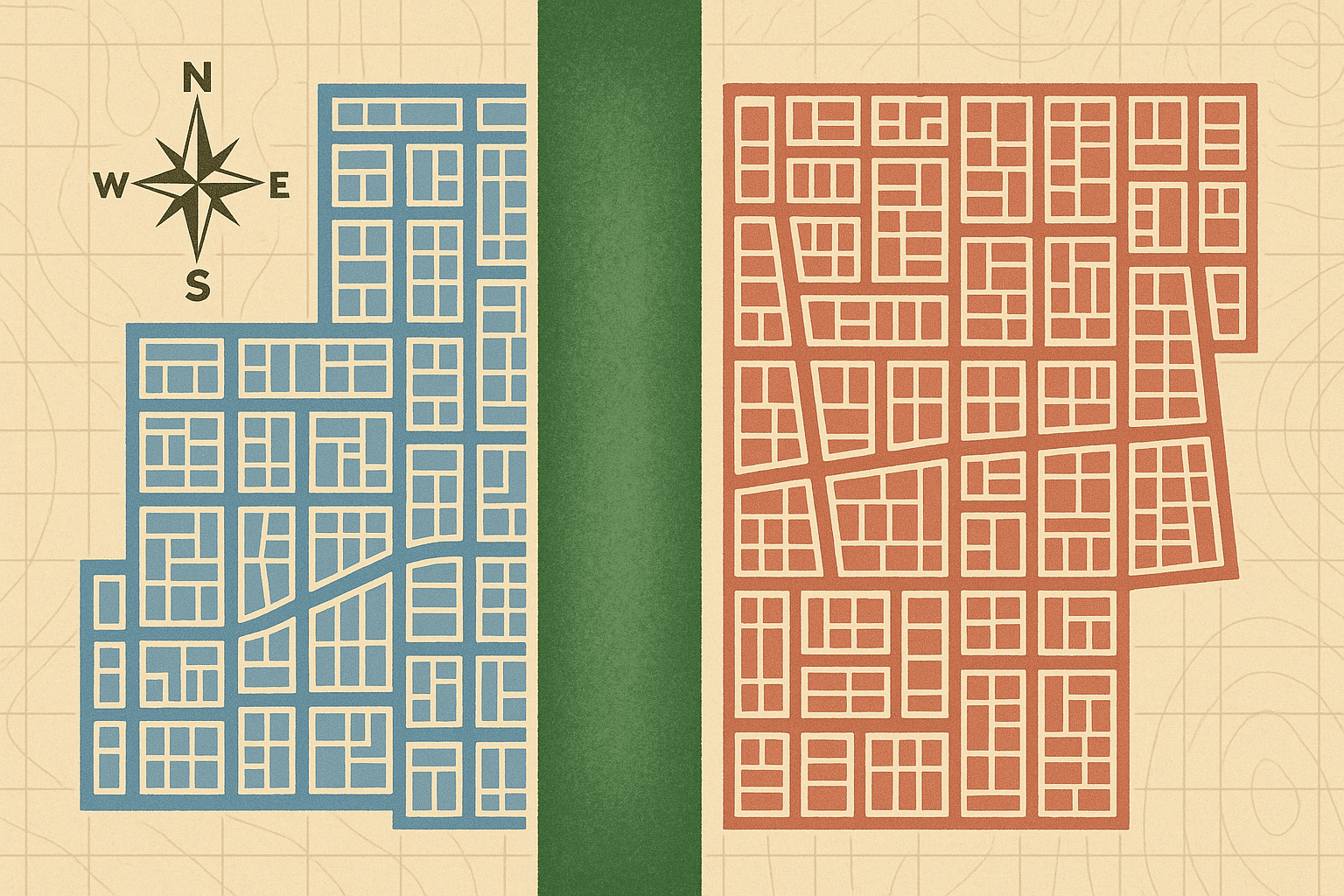

- A Tale of Two Cities: The line creates two distinct urban atmospheres. South of the line, in the Republic of Cyprus, you find the Euro, Greek language, and a distinctly southern European feel. Cross a checkpoint, and you enter the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (recognized only by Turkey), where the Turkish Lira is the currency, Turkish is spoken, and the cultural ambiance shifts immediately.

The most famous example of this division and its recent evolution is Ledra Street. For decades, this main commercial artery was blocked by a solid wall. Its opening as a pedestrian crossing in 2008 was a momentous event, transforming a symbol of division into a bridge for communication and commerce, albeit one where you must still present your passport.

An Accidental Time Capsule

Because access to the Buffer Zone has been severely restricted since 1974, it has become a de facto time capsule. The moment the ceasefire was called, time stopped. Inside this forbidden zone, an entire cross-section of mid-1970s Cypriot life is preserved in a state of arrested decay.

The most haunting example is the Nicosia International Airport. Once the bustling gateway to the island, it now sits silent and derelict within the Buffer Zone. A Cyprus Airways Trident passenger jet, stranded during the invasion, still rests on the tarmac, its paint peeling and tires flat—a ghostly monument to a bygone era. Elsewhere in the zone, car dealerships contain brand-new 1974 models gathering decades of dust. Homes remain filled with the personal effects of families who fled, expecting to return in a few days.

The Unlikely Wildlife Haven

The Green Line presents a fascinating paradox for physical geography. While it represents a tragic human division, its lack of human activity has inadvertently created a unique ecological sanctuary. This “no-man’s-land” has become a haven for flora and fauna.

With agriculture, hunting, and development forbidden, nature has reclaimed the space. The zone acts as a vital corridor for wildlife, including the rare and protected mouflon, a native species of wild sheep. Biologists have documented a rich biodiversity within the line’s confines, making it one of the most unique and accidental nature reserves in Europe. It is a powerful example of how quickly ecosystems can recover when human pressure is removed.

A Scar with a Future?

Today, the Green Line is more porous than it once was. Since the first checkpoint opened in 2003, several more have been established, allowing for greater movement of people and goods between the two sides. For Cypriots, crossing the line to work, shop, or visit friends and family has become a part of life. For tourists, it offers a surreal glimpse into one of the world’s most intractable geopolitical conflicts.

The Green Line remains a complex and powerful geographical feature. It is a physical scar on the land, a border on the map, and a wound in the Cypriot consciousness. It is both a reminder of a painful past and a space where nature thrives in humanity’s absence. As talks about reunification ebb and flow, the ultimate fate of this unique geographical phenomenon remains uncertain. Will it one day be erased, its streets reconnected and its buildings restored? Or will it remain a permanent feature on the map of Cyprus, a green line dividing an island in the sun?