The Tigris River, an artery of life that has nourished civilizations for millennia, is being fundamentally re-engineered. Along its banks, where the world’s first cities rose from the fertile soil of Mesopotamia, a new kind of monument now stands: the megadam. Far from the mud-brick ziggurats of antiquity, these colossal structures of concrete and steel are powerful agents of geographic and cultural change. Nowhere is this transformation more profound or controversial than at the site of the Ilisu Dam in southeastern Turkey, a project that has quite literally remapped a cradle of civilization.

A Concrete Giant on a Legendary River

Completed in 2019 and fully operational by 2020, the Ilisu Dam is a keystone of Turkey’s Southeastern Anatolia Project (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, or GAP), a massive regional development plan aimed at harnessing the hydroelectric and irrigation potential of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Situated in Şırnak Province, near the border with Syria and Iraq, the dam is an engineering marvel. It stands 135 meters (443 feet) high and stretches over 1,800 meters (5,900 feet) across the Tigris valley, creating a reservoir that covers more than 300 square kilometers (115 square miles).

Its primary purpose is to generate electricity, with an installed capacity of 1,200 megawatts, making it one of Turkey’s largest hydroelectric power plants. For the government, the dam represents energy independence, economic progress, and modernization for a historically underdeveloped region. But for geographers, historians, and downstream nations, it represents an irreversible alteration of a landscape freighted with immense human history.

The Drowning of Hasankeyf: A Cultural Map Erased

The most devastating and well-documented impact of the Ilisu Dam has been the complete submergence of the ancient city of Hasankeyf. This was not just a town; it was a living museum, a place of continuous human settlement for an estimated 12,000 years. Its dramatic limestone cliffs, honeycombed with thousands of Neolithic caves, towered over a bend in the Tigris. Over the centuries, it became a strategic stronghold for a succession of empires.

The layers of history were visible everywhere:

- A Roman fortress from the 4th century.

- The remnants of a magnificent 12th-century stone bridge built by the Artuqid dynasty.

- The striking cylindrical Zeynel Bey Tomb, a 15th-century masterpiece of Timurid-inspired architecture.

- The Ayyubid-era Great Mosque and the towering citadel that offered a commanding view of the river valley.

Activists, archaeologists, and residents campaigned for decades to save Hasankeyf, proposing it as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Their efforts failed. In 2019, the waters of the Ilisu reservoir began to rise, slowly and inexorably creeping up the ancient stone walls and minarets. While a few key monuments, including the Zeynel Bey Tomb and the Artuklu Hamam (bathhouse), were painstakingly relocated to a new “archaeological park” on higher ground, critics argue this is a hollow victory. The monuments have been torn from their geographical and historical context, turned into museum pieces in a new, artificial settlement. The soul of Hasankeyf—the intricate tapestry of buildings, caves, and landscape woven together by the Tigris—now lies beneath dozens of meters of still water.

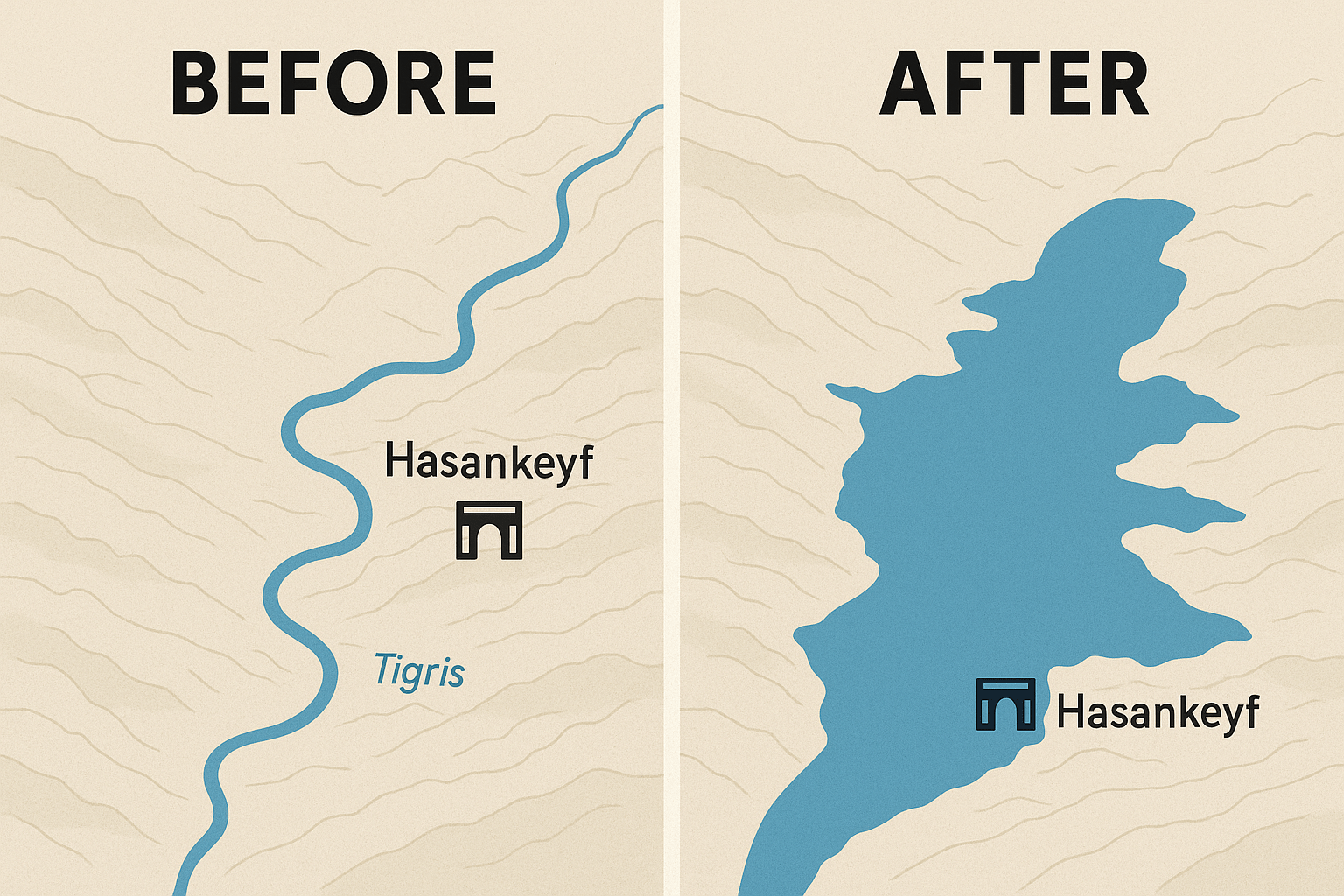

Redrawing the Physical Map: A River Transformed into a Lake

The creation of the Ilisu reservoir has fundamentally redrawn the physical map of the Upper Tigris basin. What was once a dynamic, meandering blue line on the map is now a massive, static body of turquoise water. This transformation from a riverine to a lacustrine (lake-like) ecosystem has profound consequences for the region’s physical geography.

Firstly, the dam acts as a massive sediment trap. The Tigris, like all great rivers, carries a heavy load of silt and nutrients from the mountains downstream. This sediment historically enriched the floodplains of Mesopotamia, creating the Fertile Crescent. The Ilisu Dam now blocks an estimated 90% of this sediment, starving the downstream ecosystem of essential nutrients. The long-term effect is a less fertile river valley and increased coastal erosion where the Tigris meets the Persian Gulf.

Secondly, the river’s flow is no longer governed by natural seasonal cycles of rain and snowmelt. It is now dictated by the dam’s operators, based on electricity demand and reservoir management. This artificial flow regime disrupts the life cycles of fish and other aquatic species, many of which are adapted to the natural pulse of the river.

Geopolitical Ripples Downstream

The Tigris is a transboundary river. After leaving Turkey, it flows for a short stretch along the Syrian border before entering Iraq, where it is the lifeblood for millions. The Ilisu Dam’s location, just 60 kilometers from the Iraqi border, gives Turkey immense control over the river’s flow, creating a new and tense geopolitical reality.

For Iraq, the dam is a source of existential anxiety. Reduced water flow from the Tigris threatens the country’s already fragile water security. This impacts:

- Agriculture: Iraqi farmers who depend on the Tigris for irrigation face an uncertain future.

- The Mesopotamian Marshes: This unique UNESCO World Heritage site, a vast wetland in southern Iraq, is critically dependent on water from both the Tigris and Euphrates. Reduced flow from Ilisu exacerbates its desiccation.

- Drinking Water: Major cities, including Baghdad, rely on the Tigris for their municipal water supply.

This situation exemplifies the concept of “hydro-hegemony”, where an upstream country can leverage its geographical position to exert political and economic power over downstream neighbors. While bilateral agreements exist, the dam gives Turkey a powerful bargaining chip, turning a shared natural resource into a point of international friction.

A New Reality, A Lost Heritage

The Ilisu Dam is a stark case study in the trade-offs of modern development. It produces clean energy and promises economic benefits for southeastern Turkey. Yet, in doing so, it has reconfigured the physical landscape, erased an irreplaceable center of human heritage, and created new geopolitical vulnerabilities. The map of ancient Mesopotamia has been changed forever—not by a shifting empire or a natural disaster, but by the deliberate, calculated construction of a concrete wall across a legendary river. The waters that now cover Hasankeyf are a quiet but powerful testament to what is lost when the drive to engineer the future severs its connection to the past.