What do you call the long sandwich you buy at a deli? Is it a sub, a hoagie, a grinder, a hero, or something else entirely? And what about a sweetened, carbonated beverage? Are you in the soda, pop, or coke camp? These aren’t just trivial quirks of speech. They are linguistic fingerprints, clues that trace invisible lines across the map, revealing deep-seated cultural and historical divides. Welcome to the world of dialectology, the fascinating field where linguists become geographers of the spoken word.

While we often think of borders as physical lines drawn on a map—dividing countries, states, or properties—our language creates its own set of boundaries. These are not marked by fences or border patrols, but by the subtle shift in pronunciation or the choice of one word over another. These invisible borders tell a rich story of migration, settlement, and the enduring power of local identity.

From “Pop” to “Soda”: The Cartography of Conversation

For decades, dialectologists have painstakingly worked to map these linguistic variations. The classic method involved traveling to small towns, interviewing lifelong residents (often older and less mobile, to capture the most stable form of the local dialect), and recording their answers to a long list of questions. The result was a series of maps showing where certain words or pronunciations were used, with lines called “isoglosses” marking the geographic limits of a particular linguistic feature.

In the digital age, this work has exploded in scale. One of the most famous modern examples is the Harvard Dialect Survey. Conducted online by Joshua Katz in 2002 (with data from over 350,000 respondents), it generated a stunningly detailed picture of American English. Its maps are not just academic curiosities; they are a vibrant illustration of our nation’s cultural geography.

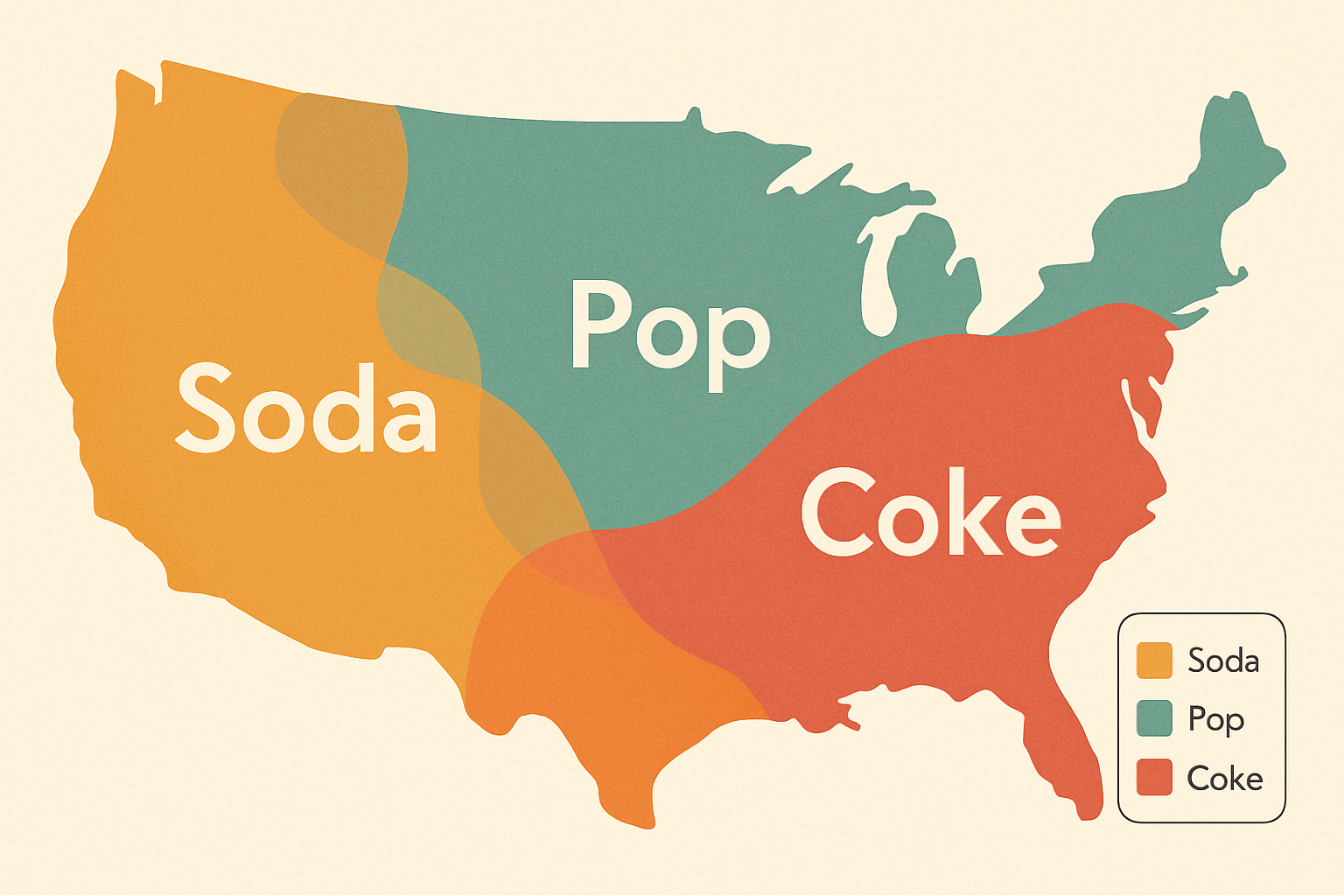

Let’s look at the classic soda/pop/coke divide:

- Soda: Dominates the Northeast, California, and the urban pockets of Florida and the Midwest around St. Louis and Milwaukee.

- Pop: Is king in the vast expanse of the Midwest, the Great Plains, and the Pacific Northwest.

- Coke: Used as a generic term for any soft drink, is overwhelmingly the term of choice across the American South.

This isn’t just a random distribution. It’s a map of cultural spheres of influence. The “pop” region, for instance, largely reflects a midwestern cultural identity, while the “soda” coasts show a different historical and cultural development. The “coke” belt in the South is a testament to the corporate geography of the Atlanta-based Coca-Cola Company, whose brand became so dominant it became the generic term itself.

The Echoes of History in Our Words

So, why do these invisible borders exist where they do? The answer almost always lies in human geography—specifically, in settlement history. The dialects spoken in a region today are often the echoes of the dialects spoken by the first major waves of settlers.

Consider the second-person plural pronoun. How do you address a group of people?

- You Guys: Pervasive across the North and West.

- Y’all: The undisputed champion of the South and Southern Midland.

- Yinz/Yous: Small, powerful pockets in Pittsburgh and the Philadelphia/New York City area, respectively.

The “Y’all Line” is one of the most distinct linguistic borders in the United States. It sharply divides the South from the rest of the country. This isn’t an accident. The term “y’all” has roots in Scots-Irish and English dialects that were brought to the coastal South and then carried westward through the Appalachian valleys and across the Gulf states. The boundary of “y’all” usage is, in essence, a map of a specific historical migration pattern. When you say “y’all”, you are unknowingly tracing a path laid down centuries ago.

Another striking example is the pronunciation of the word “greasy.” Whether you say it with a “z” sound (“gree-zee”) or an “s” sound (“gree-see”) also follows a clear geographic pattern. The “greazy” pronunciation is dominant in the South and Midland regions, a trait that linguists trace back to settlers from the south of England. The “greasy” pronunciation is standard in the North, reflecting settlement patterns from the north of England. This simple vowel sound difference is a living artifact of colonial-era migration.

More Than Just Words: Dialect, Identity, and Place

These linguistic maps do more than just show historical patterns. They reveal the powerful connection between language and identity. Using the “correct” local term is a social shorthand; it signals that you belong. Move to Wisconsin and call a water fountain anything other than a “bubbler”, and you’ll likely be corrected with a friendly smile. Order a “sub” in Philadelphia, and you’ll be told it’s a “hoagie.”

This creates a sense of shared community and place. These invisible borders, while permeable, reinforce regional identity. They are a part of what makes a place feel like itself. To be from the Midwest is to know that “pop” is the right word. To be a Southerner is to have “y’all” as a natural and essential part of your vocabulary.

Of course, in our hyper-connected world of mass media and high mobility, these lines are beginning to blur. Some linguists suggest that regional dialects are fading, creating a more homogenous “General American” English. Yet projects like the Harvard Dialect Survey show that these differences are remarkably resilient. While some features may fade, others hold strong, and new ones may even emerge.

Your Personal Linguistic Atlas

Ultimately, the language we use is a living map. It plots our origins, our travels, and our sense of community. The words you choose for everyday things—from the bug that rolls into a ball (roly-poly? pill bug? doodlebug?) to the night before Halloween (Mischief Night? Devil’s Night? Cabbage Night?)—place you on this vast, invisible chart.

These borders aren’t barriers; they are the beautiful, fascinating contours of the human landscape. They are a reminder that even within a single language, there are countless ways of seeing and describing the world, each one shaped by the unique geography and history of the people who speak it.