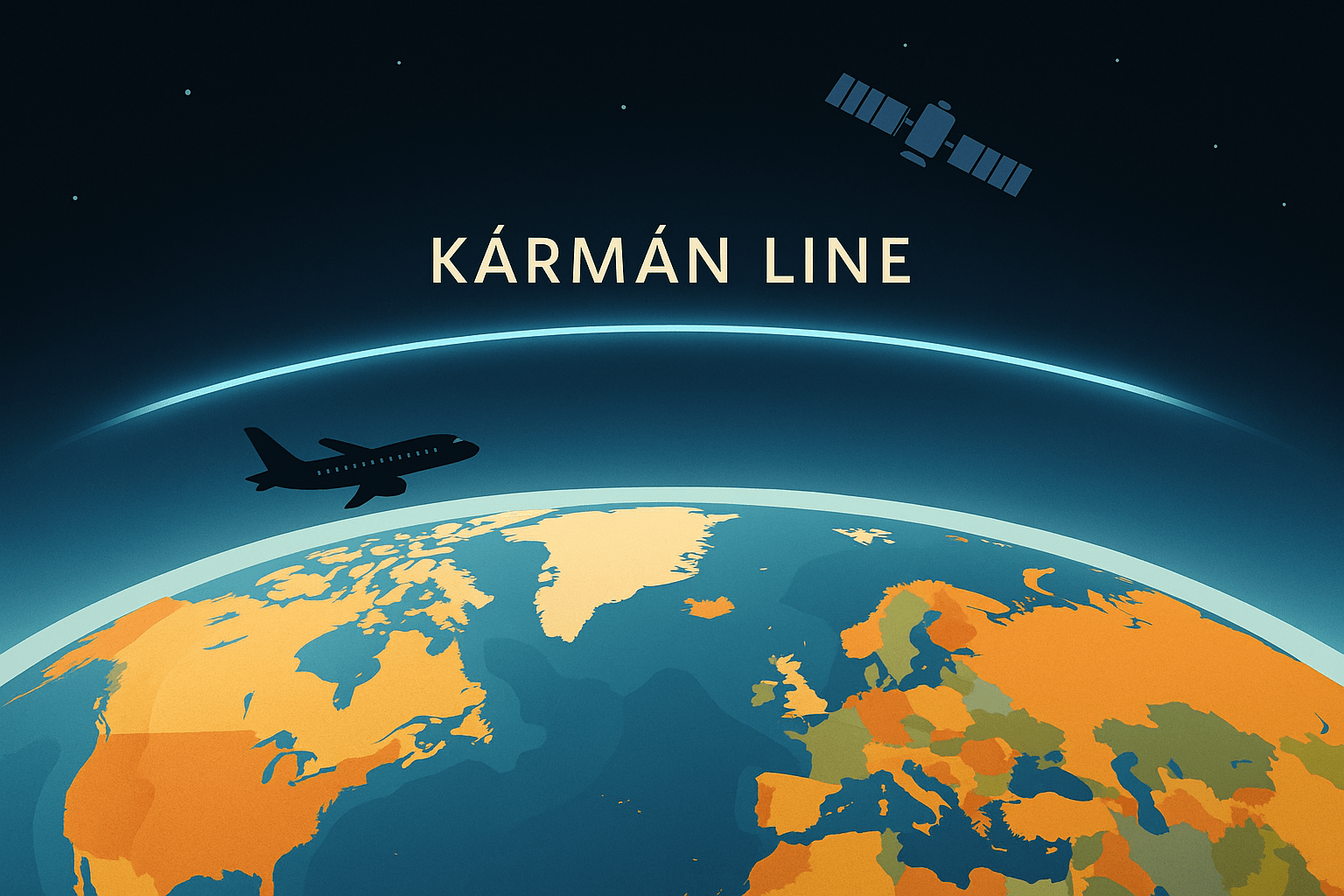

Look up at the sky. Where does it end? We can see the blue of our atmosphere, the clouds that drift within it, and the distant pinpricks of stars. But is there a definitive line where our world stops and the vast expanse of outer space begins? For geographers, pilots, lawyers, and aspiring astronauts, this is not just a philosophical question. It’s a matter of physics, sovereignty, and the future of humanity. The most widely accepted, though not universally agreed-upon, answer lies at an invisible boundary 100 kilometers (about 62 miles) above our heads: the Kármán line.

Defining the Edge of the World

The Kármán line is named after Theodore von Kármán, a brilliant Hungarian-American engineer and physicist who was a titan of 20th-century aerospace. In the 1950s, he tackled the question of where aeronautics (the science of flight within the atmosphere) ends and astronautics (the science of travel beyond it) begins.

His reasoning was elegantly simple and rooted in physical geography. To stay aloft, an airplane relies on aerodynamic lift, which is generated by the movement of air over its wings. As you go higher, the atmosphere becomes progressively thinner. To generate the same amount of lift in this rarefied air, a plane must fly faster and faster. Von Kármán calculated that there is an altitude where the air becomes so thin that, to get enough lift to support itself, a vehicle would have to be travelling at orbital velocity—the speed needed to circle the Earth without falling back down.

At this point, the vehicle is no longer “flying” in any traditional sense. It’s not being supported by the atmosphere; it’s being held up by its own immense speed, essentially becoming a satellite. This theoretical crossover point is the Kármán line. It’s the altitude where the familiar rules of our planet’s atmosphere give way to the cosmic laws of orbital mechanics.

A Vertical Border: National Sovereignty vs. The Final Frontier

This physical distinction has profound consequences for human geography and international law. Every nation on Earth claims sovereignty over its territory. This includes not only its land and territorial waters but also the airspace directly above it. This principle, codified in the 1944 Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, is why a foreign military jet cannot simply fly over the United States without permission. A country’s borders extend vertically into the sky.

But how high does that sovereignty go? If it extended infinitely, then a satellite passing over a country could be considered a violation of its airspace. Global positioning systems (GPS), satellite television, and international communication would become a geopolitical nightmare.

This is where the Kármán line provides a crucial, if informal, solution. It acts as a de facto ceiling on national airspace.

- Below 100 km: This is considered national airspace. A country controls access and can enforce its laws. It is part of that country’s sovereign territory.

- Above 100 km: This is considered outer space. Governed by the principles of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, it is treated as an international commons, free for exploration and use by all nations. No country can claim sovereignty over any part of it.

Think of it this way: the Kármán line transforms the political map of the world. It’s an invisible dome over every country, marking the end of its jurisdiction and the beginning of what the treaty calls the “province of all mankind.”

A Contested Altitude: Not Everyone Draws the Line in the Same Place

While the 100 km figure is widely used, particularly by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the world governing body for air sports and astronautical records, it is not a universally accepted legal standard. The debate over the precise border to space is a fascinating intersection of science, tradition, and national interest.

The United States, for example, has historically used a different boundary. The U.S. Air Force and NASA have often awarded astronaut wings to pilots who fly above an altitude of 50 miles (approximately 80 km). This isn’t an arbitrary number; it’s based on different atmospheric models and the point where atmospheric drag becomes more noticeable for re-entering vehicles. This discrepancy has tangible consequences in the modern era.

Consider the burgeoning space tourism industry:

- Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin launches its New Shepard capsule on a suborbital trajectory that consistently travels past the 100 km Kármán line. Its passengers are, by the FAI’s definition, unequivocally astronauts.

- Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic flies its spaceplane to an altitude of around 80-90 km. Passengers experience weightlessness and see the curvature of the Earth. By the U.S. definition, they are astronauts. By the FAI’s definition, they have flown very, very high, but have not quite crossed into outer space.

This lack of a formal, treaty-defined border to space remains one of the great unresolved issues in international law. Some nations may prefer the ambiguity, as it provides flexibility in a rapidly evolving technological landscape.

The Future Above the Line

As our reliance on space technology grows, the Kármán line will only become more significant. The region just above it, Low Earth Orbit (LEO), is becoming increasingly crowded. It’s home to the International Space Station, the Hubble Space Telescope, and massive satellite constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink, which provide global internet coverage.

The management of these orbital highways, the tracking of thousands of pieces of space debris, and the regulation of commercial activities all hinge on this fundamental separation between air and space. Issues like “hypersonic flight”, where vehicles might travel at extreme speeds through the upper atmosphere, blur the line even further. Is a hypersonic glider flying at 90 km an aircraft subject to national airspace rules, or a spacecraft enjoying freedom of passage?

The Kármán line is more than just a number. It is a concept that organizes our world. It’s a geographical boundary drawn not on land or sea, but in the thin, cold air at the very edge of our atmosphere. It separates the domain of nations from the common heritage of humanity, and as we continue our push into the cosmos, the debate over where exactly to draw this invisible line will shape the future of exploration, commerce, and our place in the universe.