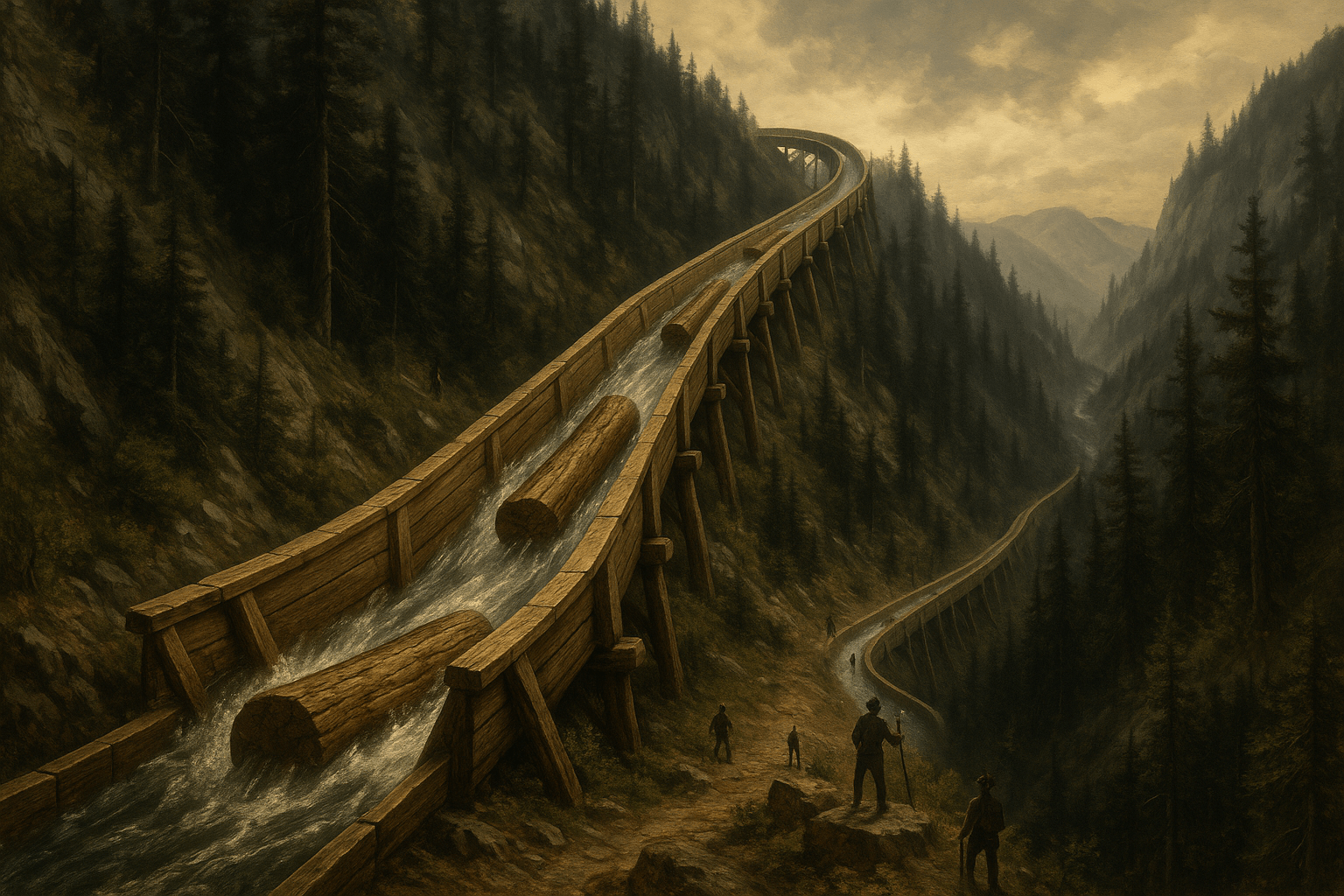

Picture a landscape of immense challenge: the rugged, roadless mountains of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Virgin forests, thick with towering pine, fir, and redwood, stood ready for harvest, but a monumental geographical problem stood in the way. How could you move millions of pounds of timber from a remote mountainside, across deep canyons and treacherous slopes, to the sawmills and railroad depots waiting miles below? The answer wasn’t a road or a railway—it was a river, built by hand.

This is the story of the timber log flume, an extraordinary feat of engineering that served as a liquid highway through the wilderness. More than just a tool, the log flume was a direct and ingenious response to physical geography, a temporary artery that reshaped the human geography of entire regions.

The Geographical Imperative: Why Build a River?

Logging has always been a battle against terrain and gravity. In the era before heavy machinery and extensive road networks, the physical geography of a forest dictated the terms of harvest. The most valuable timber often grew in the most inaccessible places: the steep slopes of the Sierra Nevada in California, the dense ranges of the Pacific Northwest, and the formidable Appalachian Mountains.

Loggers faced a daunting list of obstacles:

- Extreme Topography: Deep, V-shaped canyons, rocky outcrops, and precipitous hillsides made conventional transport impossible.

- Lack of Infrastructure: There were no roads. Building railroads into these temporary logging sites was prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

- Waterway Limitations: While river drives were a common method, they required a suitably large, navigable river that flowed in the correct direction. Many prime logging areas were landlocked, far from any useful waterway.

The solution had to be relatively cheap, quick to build, and able to harness the one constant force in the mountains: gravity. The log flume was the perfect answer. It was a purpose-built, elevated wooden channel filled with a steady stream of water, creating a controlled, gravity-fed river that could carry logs over, around, and through the most difficult landscapes.

Engineering a Wooden River

A log flume was far more than just a wooden gutter. It was a complex system requiring precise engineering, immense labor, and a deep understanding of the local environment. Its construction was a marvel of grit and ingenuity.

Anatomy of a Flume

The core of the flume was the trough, typically built in a “V” shape. This design was crucial; it used less water than a flat-bottomed trough and naturally centered the logs, reducing the chance of them jamming. These troughs were constructed from rough-sawn planks, often milled right on site from the very trees being harvested. The seams were carefully caulked with tar and oakum to be as watertight as possible.

This wooden channel rested on a massive skeleton known as a trestle. These trestles were sprawling wooden structures that carried the flume at a consistent, gentle gradient across the landscape. They spanned chasms hundreds of feet deep, clung to the sides of sheer cliffs, and snaked through forests for miles. The gradient was key; too steep, and the logs would fly out of control, smashing the flume to pieces. Too shallow, and they would get stuck, causing massive, dangerous logjams.

Of course, a flume is useless without water. A reliable source—a dammed-up mountain creek or spring—was located at the highest point. This water was the lifeblood of the operation, the “fuel” that powered this wooden transportation system.

The Human Geography of the Flume

The flume wasn’t just wood and water; it was operated and maintained by a dedicated and hardy crew. The most notable role was that of the “flume tender” or “walker.” These men patrolled miles of the flume on foot, walking along narrow planks next to the rushing water. Armed with a pike pole and an axe, their job was to prevent and break up logjams—a lonely and perilous task where a single misstep could mean a fatal fall or being crushed by tons of moving timber.

Mapping the Flumes: Monuments of a Bygone Era

Log flumes were constructed across the globe, wherever timber and mountains met, but they reached their zenith in the American West.

The Kings River Flume, California

Perhaps the most legendary of all was the Kings River Flume in California’s Sierra Nevada. Completed in 1890, this behemoth stretched over 62 miles, descending nearly 5,000 feet from the high-altitude logging camps to the lumberyard in the town of Sanger. It was an engineering spectacle, winding through the mountains like a wooden serpent. It took logs on a six-hour journey that would have otherwise been impossible, and in doing so, it created Sanger, a town whose entire economy and existence revolved around the lumber that arrived via this man-made river.

The Benson Log Flume, Oregon

Another giant was the Benson Log Flume, which ran from the forests near the Washington-Oregon border down to the Columbia River. This flume was famous for its dramatic final drop, where logs would shoot out of the flume’s terminus and splash into the river to be collected into rafts. It perfectly illustrates how flumes served as critical links, connecting inaccessible inland forests to major commercial waterways.

The End of the Line: The Decline of the Flume

For all their ingenuity, the era of the great log flumes was relatively short-lived. They were a temporary solution to a geographical problem, and once better solutions emerged, they quickly fell into disuse. The primary drivers of their decline were technology and economics.

The development of the gasoline-powered logging truck and the tough, tracked caterpillar tractor in the early 20th century was the death knell for the flume. These machines could go nearly anywhere, and they made it economically feasible to build logging roads into the heart of the wilderness. Railroads also became more advanced and capable of navigating steeper grades.

By the mid-20th century, the great flumes were abandoned. They were left to rot back into the landscape they once conquered, their trestles collapsing and their planks weathering into gray ghosts. Today, only faint traces remain—rotting timbers, old concrete footings, and overgrown clearings. Yet, these remnants are powerful monuments to a time when loggers, faced with an impossible landscape, chose to build their own river.