To understand the sheer scale of the challenge, we must first look at the geographical stage itself.

The Desert Canvas: Mecca’s Physical Geography

Mecca lies in the Hejaz region, a historically significant corridor between the Red Sea and the formidable Nafud desert. It’s not located on a major river or a fertile plain. Instead, the holy city is nestled within the Sirat Mountains, in a hot, dry, and rocky valley. Summer temperatures regularly soar above 45°C (113°F), and natural, sustainable water sources are virtually non-existent. Historically, its survival depended on the Zamzam well, a miraculous source in an otherwise unforgiving environment, and its position as a hub on ancient incense trade routes.

This unforgiving physical geography is the fundamental problem that all Hajj logistics must solve. How do you support a temporary population that swells from around 2 million permanent residents to over 4 million people in one of the world’s most water-scarce and intensely hot environments?

Mapping the Human Tide

The first and most visible challenge is managing the flow of people. This is a multi-layered geographical problem, operating on both a global and a micro-local scale.

From the World to Mecca

Pilgrims arrive from more than 180 countries, creating a massive international logistical puzzle. The primary gateway is Jeddah’s King Abdulaziz International Airport, whose Hajj Terminal is a marvel in itself. A colossal, tent-like structure, it is designed to handle immense surges of passengers, acting as a transitional space where pilgrims can prepare for the final leg of their journey to Mecca, about 70 kilometers inland.

The Ritual Pathway

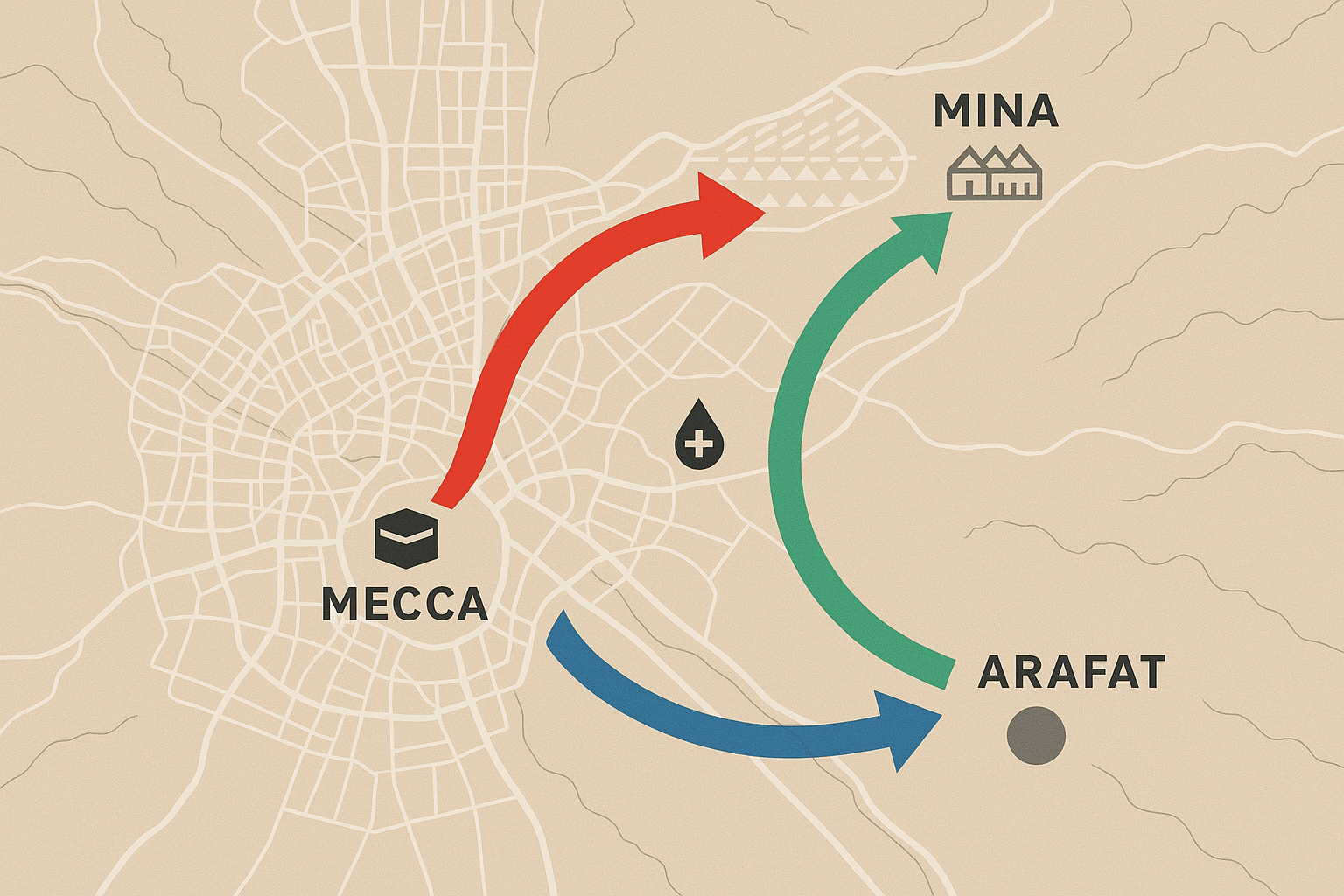

Once in Saudi Arabia, the true logistical dance begins. The Hajj rituals require pilgrims to move between several key sites in a specific sequence over five days:

- Movement from Mecca to the plains of Mina.

- A journey to the plains of Arafat for a day of prayer.

- An overnight stay at Muzdalifah.

- Return to Mina for the symbolic ‘stoning of the devil’ ritual.

- Final return to Mecca for farewell circumambulations of the Kaaba.

This prescribed path concentrates millions of people into incredibly small geographical footprints. The solution is a symphony of meticulously planned transportation and crowd control. The Al Mashaaer Al Mugaddassah Metro is a purpose-built elevated railway connecting the holy sites. For one week a year, it becomes one of the busiest metros in the world, capable of transporting over 72,000 passengers per hour in a single direction. This is supplemented by a fleet of over 20,000 buses, all coordinated to move specific national groups along designated routes at scheduled times, preventing a chaotic free-for-all.

Perhaps the most potent example of geographical engineering is the Jamarat Bridge in Mina, the site of the stoning ritual. Historically a scene of deadly trampling incidents, it has been completely redesigned. It is now a massive, multi-level pedestrian bridge, allowing for a smooth, one-way flow of pilgrims across five floors, an architectural solution to a deadly crowd-flow problem.

Life Support Systems: Sustaining the Pop-Up City

Moving people is only half the battle. Keeping them sheltered, fed, and hydrated in the middle of a desert is an even greater challenge.

Shelter: The City of Tents

The valley of Mina transforms from an empty expanse of dusty land into a sprawling, organized metropolis of over 100,000 fire-proof, air-conditioned tents. This “City of Tents” covers approximately 20 square kilometers. The tents are arranged in a precise grid, with numbered camps and color-coded sections corresponding to a pilgrim’s country of origin. This isn’t just shelter; it’s a pre-fabricated urban landscape, complete with temporary clinics, food stalls, and sanitation facilities, all erected and dismantled each year.

Water: A River in the Desert

Mecca’s average annual rainfall is a mere 110 millimeters. Providing water for millions requires a monumental feat of engineering that bypasses local geography entirely. The solution lies on the coast. Massive desalination plants, primarily in Jeddah and Shuqaiq on the Red Sea, convert seawater into fresh water. This water is then pumped through an extensive network of pipelines across the coastal plains and mountains to Mecca and the holy sites. During the Hajj, billions of liters of water are consumed. The sacred Zamzam well, while still spiritually central, now has its output managed by a high-tech pumping station and bottling plant to ensure its water is distributed hygienically and efficiently to millions.

Food and Waste: Fueling the Masses

Feeding the temporary city requires a supply chain that works with military precision. Vast industrial kitchens, some located on the outskirts of Mecca, can prepare hundreds of thousands of pre-packaged meals per day. Government authorities rigorously inspect food sources to ensure safety. The logistical aftermath is equally daunting: the pilgrims generate thousands of tons of waste daily. An army of sanitation workers equipped with compacting trucks works around the clock in a constant cycle of collection and removal, a critical service to maintain hygiene and prevent disease in such crowded conditions.

An Intersection of Faith and Infrastructure

The Hajj is, at its heart, a profound personal journey. Yet, the stage upon which it unfolds is a testament to human ingenuity and our ability to overcome immense geographical constraints. It represents the pinnacle of temporary urbanism, a pop-up megacity built on a foundation of sophisticated logistics, advanced engineering, and meticulous planning.

By mapping the flows of people, water, food, and shelter, we see a different kind of miracle: the transformation of a barren desert valley into a habitable, functioning metropolis for one of the largest gatherings of humanity on Earth. It is a powerful reminder that where human will and faith converge, even the most challenging landscapes can be reshaped.