The Great Continental Jigsaw

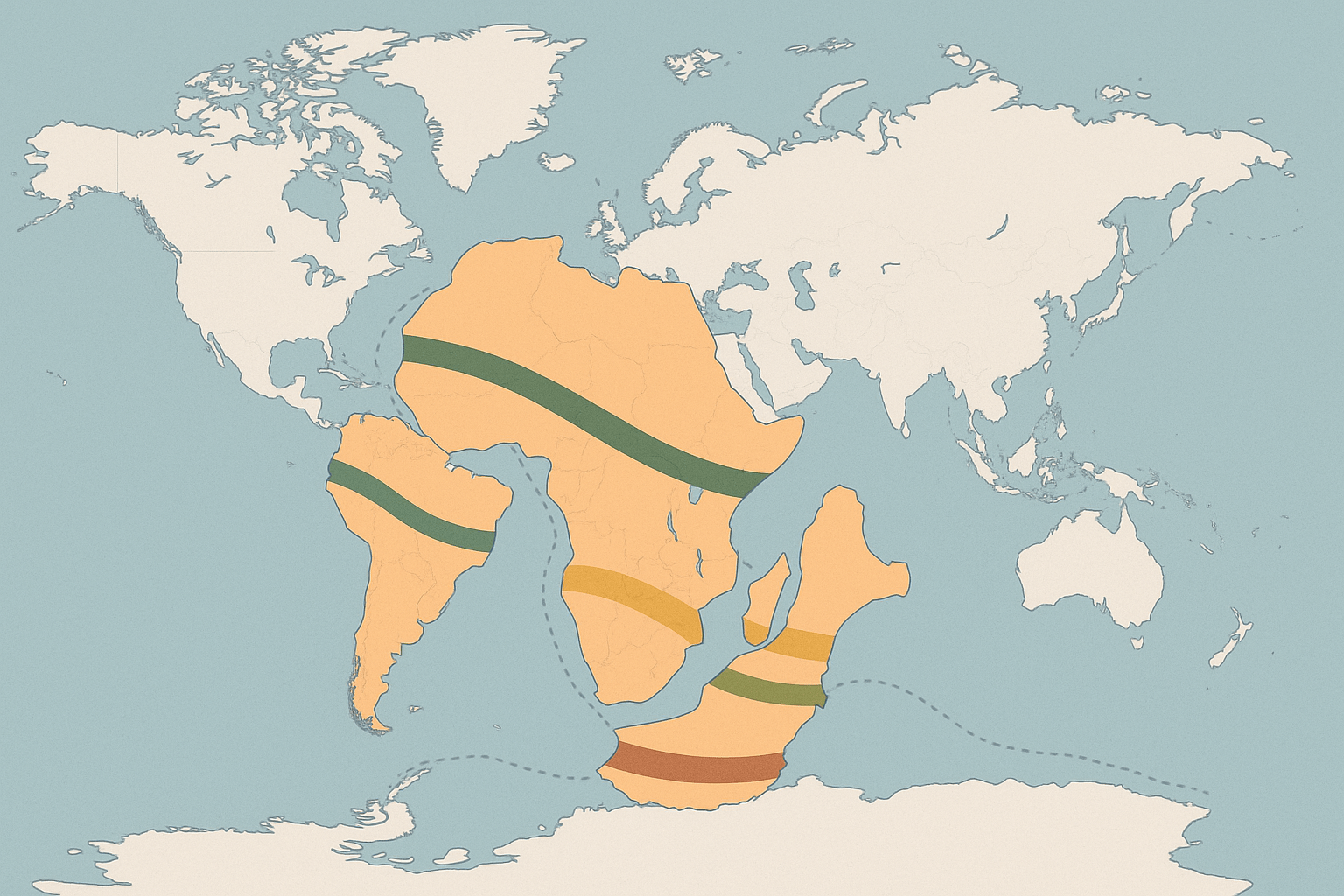

The story of Gondwana begins, as many great discoveries do, with a simple observation. For centuries, cartographers and thinkers noticed the uncanny fit between continents. The most striking is the connection between South America and Africa, but the puzzle is larger than that. Tuck the Arabian Peninsula and the horn of Africa together. Slide the western coast of Australia against the shores of Antarctica, and then nestle India into the space between Antarctica, Africa, and Australia. Suddenly, the disparate lands of the Southern Hemisphere snap together into a coherent whole. This was the core of Alfred Wegener’s theory of continental drift in the early 20th century. While the fit wasn’t perfect—erosion and time had blurred the edges—it was too compelling to ignore. It was the first clue that these continents shared a history, but much more evidence was needed to prove they once shared a single address.

Geological Handshakes Across Oceans

If these continents were once joined, they should share more than just a complementary shape. Their fundamental geology—the types and ages of their rocks—should match up across the oceans. And they do, with spectacular precision.

Consider the Cape Fold Belt, a series of dramatic, folded mountains near Cape Town, South Africa. These mountains seem to run right off the continent and disappear into the Atlantic. But travel across the ocean to the area around Buenos Aires, Argentina, and you’ll find the Sierra de la Ventana, a mountain range of the same age and same structural style. When you reassemble Gondwana, these two ranges form a single, continuous mountain chain stretching over 1,000 kilometers.

The evidence goes deeper, into the ancient cores of the continents known as cratons. The geology of the São Luís Craton in Brazil is a near-perfect match for the West African Craton in Ghana. Geologists can trace rock formations and mineral deposits from one continent to the other. Rich diamond mines in Sierra Leone, for example, correspond to similar diamond-bearing geology in northeastern Brazil. It’s a geological handshake, an undeniable connection proving these lands were once fused together.

Echoes of Ancient Life: The Fossil Record

Perhaps the most evocative evidence for Gondwana comes from the silent testimony of fossils. These remains of ancient life paint a picture of a single, unified ecosystem that stretched across lands now separated by thousands of kilometers of ocean.

Three key fossils tell much of the story:

- The Glossopteris Fern: This ancient plant is the star witness. Fossils of Glossopteris have been found in the coal fields of Australia, deep within the ice of Antarctica, across India, throughout southern Africa, and in South America. The seeds of this fern were heavy and could not have floated across vast oceans or been carried by wind. The only logical explanation for its widespread distribution is that all these continents were connected, allowing the fern to colonize a single, contiguous landmass.

- Mesosaurus: This was a small, freshwater reptile, about a meter long, that looked a bit like a miniature crocodile. Its fossils are found in only two places on Earth: the Paraná Basin in Brazil and the Karoo Basin in southern Africa. A creature adapted to fresh water could never have survived a journey across the salty, wide Atlantic Ocean. Their shared presence is irrefutable proof that these two regions were once linked by a common system of lakes and rivers.

- Lystrosaurus: A stocky, pig-sized land reptile from the Triassic period, Lystrosaurus was no swimmer. Yet, its fossils are found in South Africa, India, and even Antarctica. Finding the remains of this land-dweller on what is now the most isolated and inhospitable continent on Earth is powerful evidence. It tells us that not only was Antarctica once connected to other continents, but it was also warm enough to support thriving reptile populations.

Scars of a Great Ice Age

The final, powerful piece of evidence is carved into the bedrock itself. Around 300 million years ago, Earth experienced a major ice age. As massive glaciers and ice sheets expanded, they dragged rocks and debris along their base, gouging deep, parallel scratches, known as glacial striations, into the underlying rock. When the ice melted, it left behind deposits of unsorted sediment called tillite.

Geologists found these ancient glacial scars and deposits across South America, southern Africa, India, and Australia. In their present locations, they make no geographical sense. In India, for example, the striations show that the glaciers moved from the south—from the warm Indian Ocean. In South America, they appear to have crept up from the Atlantic. This is physically impossible; glaciers flow downhill from cold, high-altitude centers.

However, when you reassemble the continents into Gondwana, the picture becomes crystal clear. The striations on all the continents align perfectly, radiating outwards from a central point. That point, located over southern Africa and Antarctica, was the South Pole during that period. The evidence of a single, massive polar ice cap covering the southern part of Gondwana is undeniable.

The Ghost on the Map

By piecing together the continental fit, the geological formations, the fossil distributions, and the glacial scars, we can draw the map of this lost world. Gondwana was a supercontinent of immense scale that existed for hundreds of millions of years, centered around the South Pole but stretching into warmer latitudes. It was a world of vast fern forests, strange reptiles, and towering mountain ranges, all under a single southern sky.

Its eventual breakup, which began around 180 million years ago, shaped the world we know today. It created the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, isolated Antarctica at the pole, and sent India on a long journey north to collide with Asia, forming the Himalayas. The legacy of Gondwana is still with us, influencing everything from the distribution of marsupials in Australia to the location of coal and diamond deposits. It’s a reminder that the geography we take for granted is fleeting, and that the face of our planet is in a constant, majestic state of change.