Imagine a classic Pacific atoll: a perfect ring of palm-fringed sand encircling a turquoise lagoon. It’s an image synonymous with paradise. Now, imagine that entire atoll—lagoon and all—being lifted by an invisible hand, dozens of meters into the sky, leaving its ancient coral skeleton exposed to the elements. This is no fantasy; this is a makatea, one of the most fascinating and formidable geographical phenomena in the ocean.

These uplifted coral atolls are geological marvels, island fortresses that tell a story of immense planetary power, evolutionary isolation, and human resilience. They are the islands that, quite literally, refused to sink.

From Sunken Volcano to Raised Fortress: The Geology of Uplift

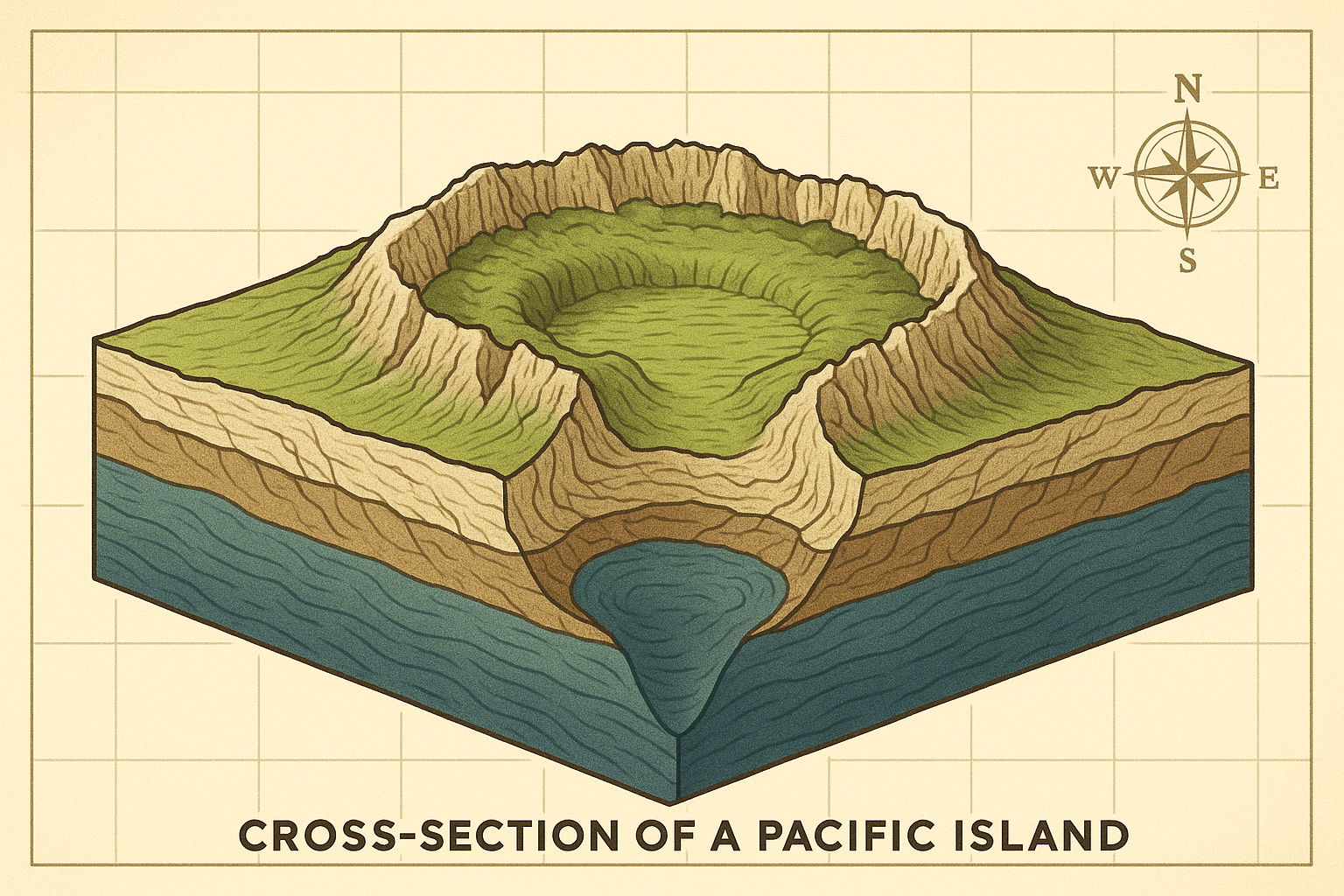

To understand a makatea, you first have to understand its origin as a regular atoll. The process, first theorized by Charles Darwin, begins with a volcanic island. Over millions of years, the volcano becomes extinct and begins to slowly sink under its own weight. As it sinks, a fringing coral reef grows around its shoreline, constantly reaching up towards the sunlight.

Eventually, the volcano disappears completely beneath the waves, leaving only a ring of coral—a barrier reef—enclosing a central lagoon. This is the atoll we know and love. But for a makatea, the story doesn’t end there. A powerful geological event occurs, reversing the sinking process and thrusting the entire formation upwards.

This uplift happens in one of two primary ways:

- Tectonic Collision: When two of Earth’s tectonic plates slowly collide, the crust can buckle and warp, pushing the seafloor and any islands on it high above sea level.

- Lithospheric Flexure: This is a more localized and dramatic process often called the “volcanic teeter-totter.” When a new, massive volcanic island (like Tahiti) forms on a tectonic plate, its immense weight presses down on the flexible crust. Like a person sitting in the middle of a seesaw, this causes the edges of the plate to bulge upwards. Older, nearby atolls sitting on this bulge are lifted out of the water. The island of Makatea in French Polynesia, the namesake for this type of landform, was lifted in precisely this way by the weight of nearby Tahiti and Mehetia.

The result is a fossilized atoll. The former lagoon floor becomes a central plateau, and the old reef rim forms towering, near-vertical cliffs around the island’s perimeter. Sometimes this uplift happens in stages, creating a series of distinct terraces that look like giant steps climbing out of the ocean.

The “Feo”: A Treacherous Landscape of Razor-Sharp Limestone

The defining feature of a makatea is its surface. The Polynesian word makatea translates to “white rock”, but this description belies its true nature. Over hundreds of thousands of years, rainwater, which is naturally slightly acidic, has dissolved the porous coral limestone, creating a brutally sharp and pitted landscape known as karstic terrain. In French Polynesia, this treacherous surface is called feo.

Imagine a terrain of needle-like pinnacles, deep sinkholes, hidden caves, and blade-sharp ridges, all jumbled together in an impassable maze. Walking on feo is incredibly dangerous and can shred boots and skin with ease. This geological structure has profound consequences:

- Lack of Soil: There are few flat surfaces for soil to accumulate. What little exists is found in small depressions and fissures.

- Poor Water Retention: The limestone is like a sponge. Rainwater drains almost instantly through the cracks and fissures, leaving the surface dry and making fresh water a scarce resource.

- A Natural Fortress: The sharp feo cliffs and treacherous interior make the island extremely difficult to traverse, effectively isolating interior sections from the coast.

An Isolated Eden: The Ecology of a Raised Island

This fortress-like geology creates a unique ecological laboratory. Isolated from the outside world and offering a harsh environment to colonize, makatea islands are hotspots for endemism—the evolution of species found nowhere else on Earth.

Plants must be incredibly resilient, adapted to anchor themselves in limestone cracks with minimal soil and survive periods of drought. On Henderson Island, an uninhabited makatea in the Pitcairn group, 9 of the 10 flowering plant species are endemic. The island’s severe isolation allowed its wildlife to evolve without predators. It is home to four endemic land birds, including the flightless Henderson Crake, which thrives in the protected, rugged interior.

These ecosystems stand in stark contrast to low-lying sandy atolls, whose terrestrial life is often limited and vulnerable to being wiped out by tsunamis and storm surges. A makatea’s elevation provides a safe haven, allowing unique life forms to develop over millennia.

Human Life on “The Rock”

For humans, life on a makatea presents a set of extreme challenges. The lack of surface water means communities have historically relied on collecting rainwater or accessing freshwater lenses that gather in deep caves and grottos. Agriculture is a constant struggle. Islanders developed ingenious methods of cultivating crops like taro and bananas in natural depressions or by building up soil in excavated pits.

However, the unique geology also provided a historical windfall. Over eons, seabirds nesting on these islands left behind immense quantities of guano. This guano, washed into the depressions of the limestone, created some of the world’s richest deposits of phosphate rock. In the 20th century, islands like Nauru, Banaba (Ocean Island), and Makatea itself were subject to intensive phosphate mining. This brought temporary wealth but left behind a devastating ecological legacy—a “lunarscape” of stripped land that is still recovering today.

Where to Find These Geological Oddities

Makatea are scattered across the Pacific, each with its own unique character:

- Niue: A self-governing nation that is one of the world’s largest single uplifted coral atolls. Known as “The Rock of Polynesia”, its entire geography is defined by its makatea structure.

- Nauru: The world’s smallest island nation, its history and economy are inextricably linked to the boom and bust of its phosphate resources.

- The Southern Cook Islands: A cluster of makatea, including ‘Atiu, Mangaia, and Mauke, known for their system of caves, coffee plantations grown in fertile soil pits, and distinct culture.

- Henderson Island: A UNESCO World Heritage Site, this uninhabited island is a near-pristine example of a makatea ecosystem, offering scientists a glimpse into an evolutionary process untouched by humans.

Makatea are far more than just “raised islands.” They are geological time capsules, living laboratories for evolution, and powerful symbols of the dynamic, ever-changing nature of our planet. They challenge our idyllic perceptions of a Pacific island, replacing soft sand with sharp stone, but offering in return a deeper story of survival, adaptation, and raw geological power.