These remarkable artifacts are more than just maps; they are a profound expression of a deep relationship between a people and the sea. Unlike Western maps, which meticulously detail the fixed points of land, Marshallese stick charts map the invisible, dynamic forces of the ocean—the swells, currents, and wave patterns that reveal the way to land long before it can be seen.

A World of Water and Atolls

To understand the stick chart, one must first understand the geography of the Marshall Islands. Located in the central Pacific, the Republic of the Marshall Islands is a sprawling nation of over 1,200 islands and islets, grouped into 29 low-lying coral atolls and 5 solitary islands. These slivers of land are scattered across more than 750,000 square miles of ocean. For the Marshallese people, the ocean was not a barrier but a highway, and the ability to navigate it was the key to trade, communication, and survival.

The challenge was immense. Atolls are notoriously difficult to spot from a distance, often rising only a few feet above sea level. A navigator could be a dozen miles away from an atoll and see nothing but an empty horizon. The solution was not to look for the land, but to feel its presence through the water.

Reading the Ocean’s Language

Marshallese navigators, known as ri-meto, learned to interpret a complex language written in waves. Open ocean swells, generated by consistent trade winds, travel in predictable patterns for thousands of miles. The stick charts are primarily a guide to these patterns.

The principal swell, originating from the strong northeasterly trade winds, is called the rilib. Other, weaker swells come from different directions, such as the kaelib from the southwest. In the open ocean, these swells move in a regular, uninterrupted rhythm.

The genius of the system lies in understanding how this rhythm is disrupted. When an ocean swell encounters an island, it refracts and bends around it, much like light bending through a lens. Furthermore, waves hitting the shore reflect back out to sea, creating a counter-swell. This interaction creates a complex interference pattern—an area of choppy, confused water—that can be felt in a canoe up to 20-30 miles away from the island causing it. An island, though invisible, announces its presence by creating a “wave shadow” and a unique signature of disturbed water. The stick charts are a physical representation of this invisible phenomenon.

The Anatomy of a Stick Chart

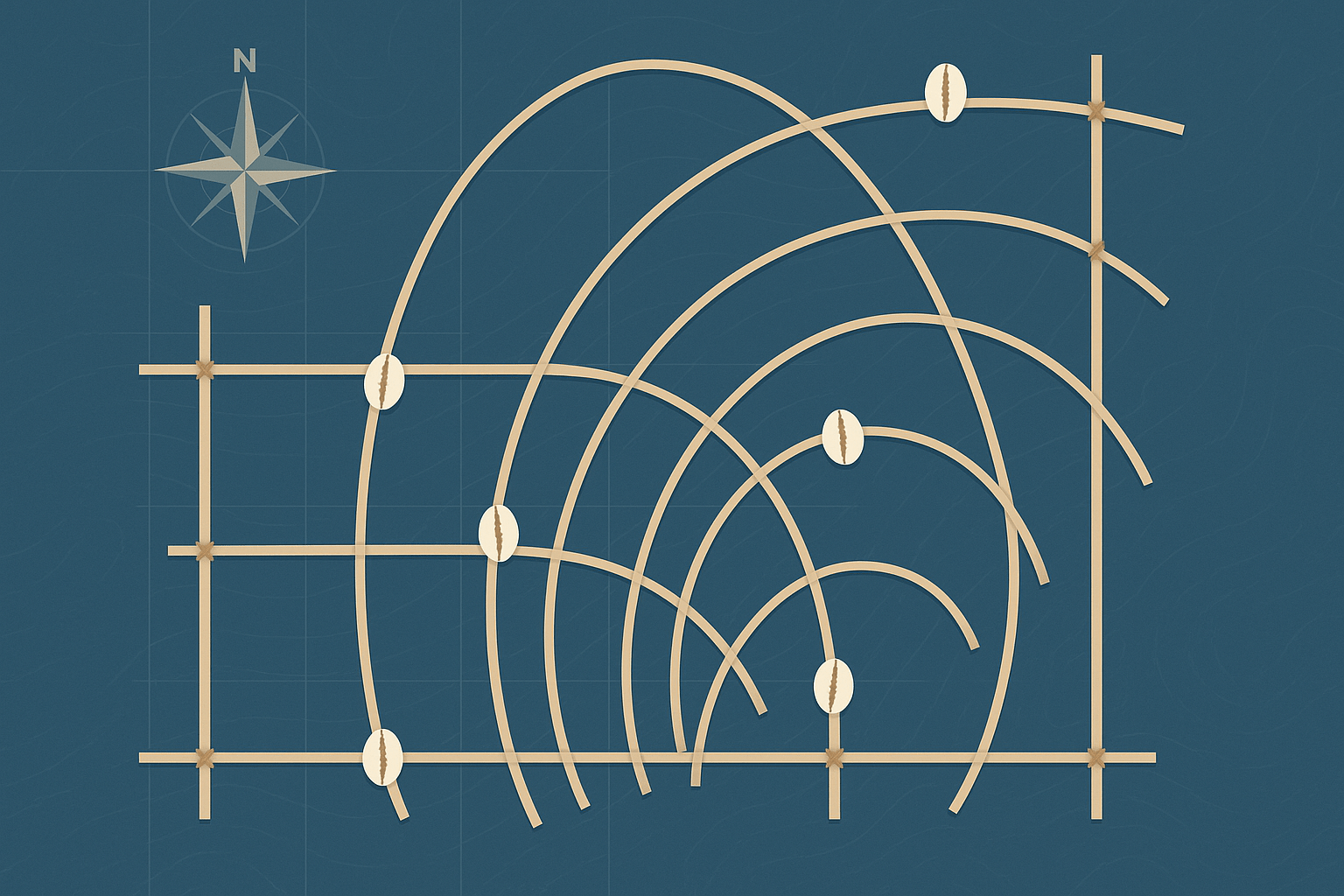

Made from the flexible midribs of coconut fronds, which are tied together with coconut fiber, stick charts are both abstract and practical. The components are elegantly simple:

- Sticks: The straight and curved sticks represent the patterns of the dominant ocean swells. Curved sticks illustrate how swells bend and are deflected by the presence of an island.

- Intersections: The points where different sticks cross indicate regions of conflicting swells, where navigation becomes particularly challenging and the motion of the canoe would feel chaotic.

– Cowrie Shells: Tied onto the stick framework, these shells mark the locations of the atolls and islands.

Navigators created and used three distinct types of charts:

- Mattang: These were not maps of any specific location but were abstract training tools. A mattang was a conceptual diagram used by an experienced navigator to teach a student the fundamental principles of how swells interact with a single island. It showed refraction, reflection, and the resulting zones of disturbance, allowing apprentices to learn the theory before venturing out.

- Meddo: More geographically specific than a mattang, a meddo chart shows a part of one of the Marshall Islands’ two main island chains (the Ratak “Sunrise” chain or the Ralik “Sunset” chain). It would depict the actual locations of several atolls, the prevailing swells between them, and the specific wave patterns a navigator would encounter on a journey.

- Rebbelib: The most comprehensive chart, a rebbelib showed a much larger area, sometimes encompassing all or most of the Marshall Islands. These were large-scale maps used to understand the relationships between islands over vast distances and plan major voyages.

A Mnemonic Device, Not a Pocket Guide

A crucial detail about stick charts is that they were never carried on a voyage. They were not consulted on the deck of a canoe like a modern chart. Instead, they were intensely personal mnemonic devices, used for study and memorization on land.

A navigator would spend years, often from childhood, learning to construct and interpret these charts. But the ultimate goal was to internalize the information so completely that the physical chart became unnecessary. The true map was held in the navigator’s mind and body. During a voyage, the ri-meto would often lie flat on the bottom of the canoe (wā) to be more sensitive to the ocean’s motion. They used their entire body as an instrument, feeling the subtle changes in the canoe’s pitch, roll, and yaw to interpret the wave patterns and pinpoint their location relative to the nearest piece of land.

The Fading Art of Wave Piloting

Today, the ancient art of wave piloting is critically endangered. The arrival of gasoline-powered motorboats and, more recently, GPS technology has rendered this sophisticated knowledge system largely obsolete for daily travel. The long, arduous training process is a commitment few in the modern world can make.

However, the stick charts remain a powerful symbol of Marshallese identity and a stunning example of indigenous science. They are housed in museums around the world, recognized as masterpieces of cartography and human ingenuity. Efforts within the Marshall Islands are ongoing to document and preserve this knowledge, ensuring that the wisdom of the ri-meto is not lost to the waves of time. These charts remind us that long before technology mapped our world for us, humans found extraordinary ways to read the earth’s own signals, navigating not by what they could see, but by what they could understand.