In the south of France, the weather isn’t just a topic of conversation; it’s a living entity with a name, a personality, and a will of its own. It whistles through ancient alleyways, rattles shutters, and sends dust devils dancing across sun-baked fields. This force is the Mistral, a fierce, cold wind that barrels down the Rhône Valley from the north. But to see the Mistral as mere meteorology is to miss its profound role as an unseen sculptor, a relentless architect that has forged the very character of Provence.

The Making of the “Master Wind”

Before you can understand its impact on people, you must first understand the wind itself. The Mistral—whose name is derived from the local Occitan word for “masterly”—is a powerful katabatic wind. It’s born from a classic atmospheric pressure clash: a high-pressure system forming over the Bay of Biscay or central France pushes air towards a low-pressure area over the Gulf of Genoa in the Mediterranean.

As this mass of cold air moves south, it is funneled into the narrow corridor of the Rhône River Valley, with the Alps to the east and the Massif Central mountains to the west. This natural channel acts like a giant bellows, dramatically accelerating the air. The result is a ferocious, gusting wind that can reach speeds of over 100 kilometers per hour (62 mph). It is notoriously cold, dry, and persistent, often blowing for days on end, most commonly in winter and spring.

While it can bring discomfort and damage, the Mistral is also responsible for one of Provence’s most celebrated assets: its brilliant, crystalline light. The wind’s dry, powerful nature sweeps the sky clean of clouds, haze, and pollution, creating an atmosphere of exceptional clarity and an average of over 300 sunny days a year.

Architecture Against the Onslaught

For centuries, the people of Provence have not fought the Mistral; they have adapted to it, embedding a deep respect for its power into the very bones of their buildings. This is human geography in its purest form—a dialogue between people and a dominant physical phenomenon.

Observe a traditional Provençal farmhouse, or mas, and you’ll see a structure designed for defense:

- The Blank North Wall: The most striking feature is the formidable, windowless wall facing north, directly into the teeth of the wind. This solid stone facade acts as a shield, bearing the brunt of the Mistral’s fury and preventing cold air from penetrating the home.

- South-Facing Life: In stark contrast, the south side of the mas is open and inviting. Doors, large windows, and terraces are all oriented south to capture the sun’s warmth and light, sheltered from the wind’s assault. The life of the home happens here, in the protected lee of the building.

- Anchored Roofs: Roofs are typically low-pitched to offer less resistance to the wind. They are covered in heavy, curved terracotta tiles (tuiles canal) that are often layered and sometimes even weighted down with stones along the edges to keep them from being ripped away by powerful gusts.

This architectural DNA extends to entire villages. Many older towns are built on hillsides, nestled just below the crest on the southern slope for protection. Their streets are often narrow and winding, a deliberate design choice not just for defense in medieval times, but also to break up the wind’s velocity and create calmer microclimates within the town walls.

Cultivating a Landscape of Resilience

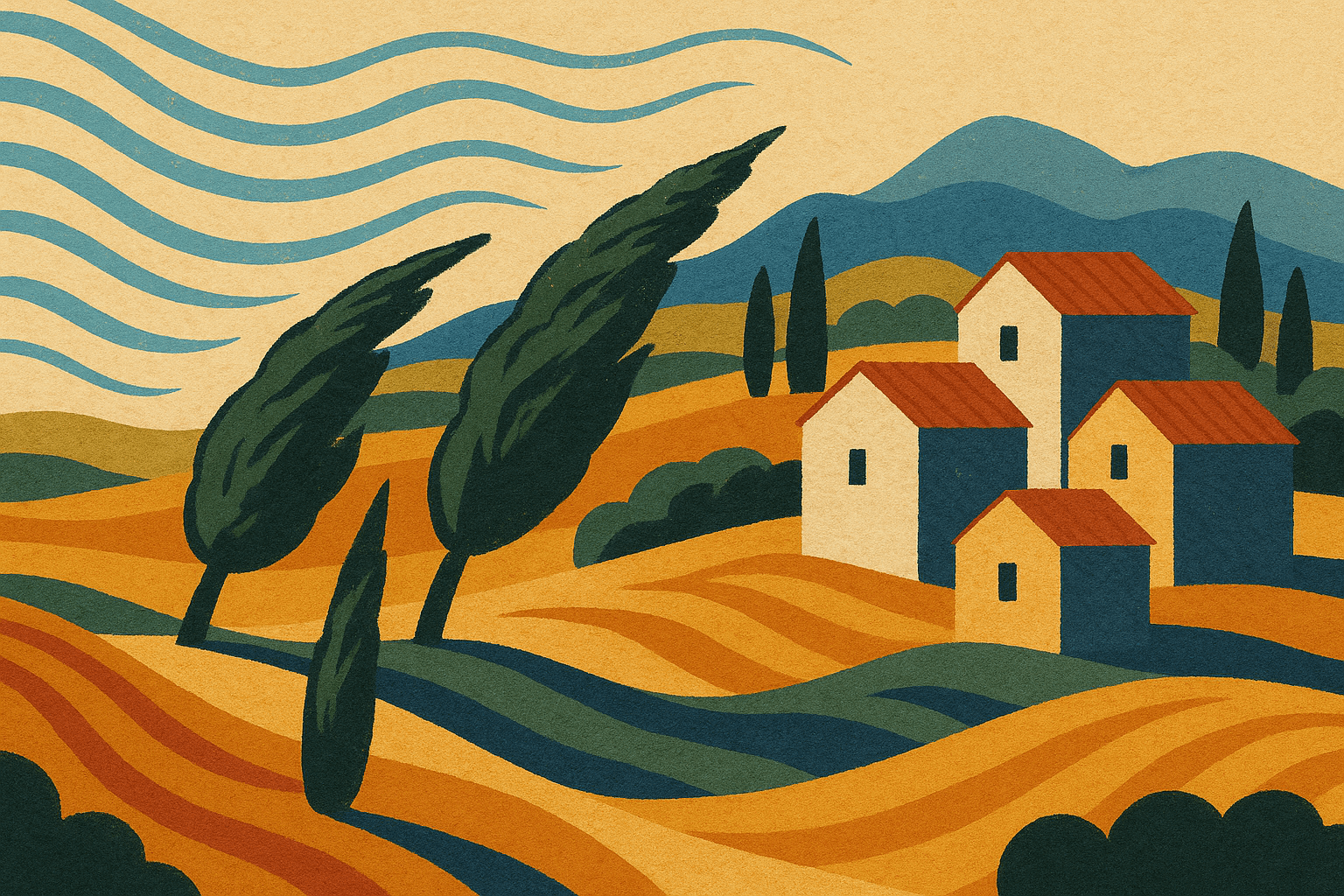

The Mistral’s influence is just as visible in the agricultural landscape. Driving through the countryside of the Luberon or around the Alpilles, you cannot miss the iconic, dark green lines of cypress trees standing sentinel beside the fields. These are not merely decorative; they are essential infrastructure.

Planted in dense rows, these cypress hedges act as windbreaks (brise-vents), filtering the wind’s force and protecting the valuable crops behind them. They are a testament to generations of agricultural wisdom, creating pockets of relative calm where more delicate produce can survive. Without these natural barriers, the fertile plains would be far less productive.

The wind’s character also dictates what can be grown. The Mistral is a double-edged sword for farmers:

- The Blessing: Its dry nature is a powerful ally for viticulture and olive growing. The wind dries moisture from the vines and trees after rain, significantly reducing the risk of fungal diseases like mildew and rot. This cleansing effect is a key component of the celebrated terroir that produces world-class rosé wines and fruity olive oils.

- The Curse: Its sheer force can snap branches, strip blossoms from fruit trees, and dehydrate young plants. Therefore, the crops that define Provence—lavender, grapevines, and olive trees—are inherently tough, woody, and resilient, perfectly adapted to withstand the periodic onslaught.

The Wind in the Artist’s Brush

The Mistral does more than shape buildings and fields; it has seeped into the region’s creative soul. The clear, intense light it leaves in its wake attracted a wave of artists in the 19th and 20th centuries, but it was the wind itself that found its way onto the canvas of Vincent van Gogh.

During his time in Arles and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Van Gogh had an intimate and often frustrating relationship with the Mistral. In letters to his brother Theo, he complained of being unable to work outdoors, of his easel being blown over, and of the “furious” and “tiresome” wind. Yet, this struggle seems to have energized his work. The swirling, dynamic energy of the Mistral is palpable in the writhing forms of the cypress trees and the turbulent, churning skies of masterpieces like The Starry Night and Wheatfield with Cypresses. The wind is not just a subject; it is the very motion of his brushstroke, a visible force field that animates the entire landscape.

The Mistral forced Van Gogh to paint with speed and intensity, to capture a world in constant, violent motion. In this way, a meteorological phenomenon was transformed into a signature artistic style.

From the silent, stoic walls of its farmhouses to the swaying lines of its cypress trees and the wild genius of its most famous art, Provence is a land defined by the push and pull of the Mistral. It is a powerful reminder that geography is not just the stage on which human history unfolds; sometimes, it is the most active and influential character in the story.